Learning from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s gives us models for action as we examine the honest history of Black Americans’ struggle for freedom and equality. When we connect historical learning to current events, we can apply our knowledge to analyze conditions today and engage in collective and individual actions to achieve a more just society.

The following 10 key concepts and main points can help us learn about and from the movement, encouraging us to think critically about the complexities of this history.

[Note: These key concepts are adapted from LFJ’s Teaching the Civil Rights Movement framework, published in 2023.]

Strategies of the Movement

1. Movement leaders and organizers combined legal, legislative and activist strategies in the late 1940s and 1950s for achieving political and social equality, which advanced the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

- The movement for racial equality drew on a wide variety of tactics for securing civil rights, including legal challenges to segregation, community organizing and direct action. Southern Black communities were at the center of the political challenge of the movement.

- Using direct action, local groups organized boycotts and protests. One of the most famous of these was the Montgomery Bus Boycott. This yearlong protest, beginning in December 1955 and organized by a broad coalition, ultimately played a role in a Supreme Court decision mandating the desegregation of city buses.

- The legal strategy of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) culminated in a series of Supreme Court rulings that expanded rights for African Americans across the country, including rulings desegregating buses and successful challenges to laws that segregated schools and restricted voting.

- The most famous legal victory of this era was the 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, in which the Supreme Court ordered the desegregation of public schools, striking down the “separate but equal” doctrine established by Plessy v. Ferguson

Hostile Opposition to the Movement

2. The Civil Rights Movement faced hostile opposition from white supremacists across the country who used various tactics – from cultural campaigns to legal strategies to terrorist attacks – to try to slow or prevent its work.

- Faced with a changing country and demands for Black equality, white supremacists across the U.S. continued to use racial terror against Black people and other people of color. This violence included the murders of Black people.

- Across the nation, violence against activists – including police violence – remained commonplace and brutal. It included lynchings, bombings, assassinations and incarceration, extending well beyond the South to urban centers like Oakland, Chicago, and New York City.

- Opposition to the movement came in many forms, including from white elected officials at the federal, state and local levels; local opposition to school integration; pushes for the disenfranchisement of Black voters; the increased popularity of racist philosophies; and the formation of “white citizens’ councils” – local groups designed to maintain white power.

- At the onset of the Cold War in the 1950s, members of the U.S. House of Representatives led anti-communist purges. Noted intellectuals and activists were stigmatized and persecuted for perceived communist sympathies.

Growth of the Movement in the 1960s

3. As the Civil Rights Movement grew, local and national organizations and grassroots groups employed a variety of methods, aims, philosophies and strategies to achieve their goals, including an expanded emphasis on direct action.

- The 1960s showed the power of nonviolent direct action as a tool for change, beginning in Greensboro, North Carolina, with a series of student-led sit-ins of segregated businesses. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) quickly became the main engine of student activism in the movement.

- The Freedom Rides, a form of direct action sponsored by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), challenged the segregation of interstate buses and terminals. Freedom Riders were Black and white volunteers who rode buses through the South together. They were attacked, beaten and jailed, but many chose to remain in the South after their release to help start local movements.

- Marches and protests drew attention to the movement, and violence against protesters spurred change on a national level. In 1963, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) led a campaign to protest segregation and racism in Birmingham, Alabama, culminating in a march by thousands of African Americans – including children – who were viciously attacked by the police. The resulting images shocked and outraged viewers around the world, prompting the Kennedy administration to finally intervene and help negotiate for desegregation.

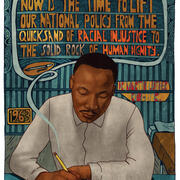

- The 1963 March on Washington, during which Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, drew a crowd of more than 250,000 people from across the United States.

- Across the South, organizing focused heavily on the right to vote. In Mississippi, activist groups coordinated to organize the 1964 Freedom Summer push to register eligible African Americans to vote. Freedom Summer workers and volunteers faced profound resistance that included the murders of civil rights workers.

- In Alabama, activists organized a voting rights campaign in Selma, leading to the famous 1965 Selma to Montgomery march and the events of “Bloody Sunday,” in which peaceful marchers were attacked and beaten.

- Nonviolence was not the only organizing philosophy of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. It was common for activists to believe in armed self-defense. Armed escorts routinely protected protesters engaged in nonviolent direct action.

Key Legislative Achievements and Continued Struggles

4. The civil rights activism of this period led to several key legislative achievements. However, even after the courts and Congress enacted new civil rights and voting protections during this period, racial discrimination continued and African Americans across the country still lacked access to quality education, well-paid jobs, health care and decent housing.

- Key pieces of federal legislation included the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination in public accommodations; the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which extended protections to voters in the South; and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which made housing discrimination illegal.

- The Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education provided a key victory of the movement in outlawing de jure school segregation. But it did not result in widespread, immediate school integration. Many white families withdrew their children from integrating schools, and persistent housing segregation meant many neighborhood schools remained segregated.

- While the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made employment discrimination illegal, large labor unions in the North continued racially discriminatory practices well into the 1970s. This long refusal to integrate weakened organized labor and reduced the economic opportunities of American workers.

- While the Voting Rights Act of 1965 made poll taxes, literacy tests and other undue burdens illegal, many districts quickly found other ways to suppress the vote of African American citizens – even before several protections afforded by the Voting Rights Act were overturned by the Supreme Court in the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision.

- While the 1968 Fair Housing Act made housing legally accessible to African Americans, economic barriers and hostility to integration persisted. Federally mandated housing policies created intentionally segregated communities, and many neighborhoods were organized so that their schools were entirely white.

- Persistent and profound economic and social inequality continued across the country. The summers of the late 1960s saw a series of urban uprisings in places like Los Angeles’ Watts neighborhood and Detroit.

Black Nationalism and Black Power Movements

5. The Black nationalism and Black Power movements in the 1960s attracted young activists frustrated with the slow pace of progress and the mainstream emphasis on integration.

- With deep roots in the “race first” philosophy of Marcus Garvey, Black nationalism called for Black solidarity and political self-determination. The Nation of Islam (NOI), which recruited Malcolm X, was an early proponent of Black nationalism, and though Malcolm X later split from the NOI, the call for Black self-determination continued to resonate with many people engaged in the struggle for Black freedom.

- In 1966, SNCC activist Stokely Carmichael’s call for “Black Power” drew on rural Black organizing traditions and Black nationalist ideas to push the movement toward the acquisition of economic and political power.

- The Black Panther Party, founded in Oakland, California, in 1966, was envisioned as a revolutionary organization that would facilitate the self-determination of Black communities while protecting them from police violence.

- The federal government allied both with and against the Black freedom struggle. The FBI targeted individual activists and civil rights organizations, including SNCC, SCLC and the Black Panther Party.

Shift in Emphasis to Address Continuing Injustices

6. Following major legislative victories in the 1960s, the movement shifted its emphasis to address continuing injustices more directly.

- Before his 1968 assassination, Martin Luther King Jr. became more focused on the underlying causes of racial oppression. His speeches and writings focused increasingly on economic inequality, the need for structural reforms, and challenges to the American war in Vietnam.

- The movement did not end with King’s assassination. African Americans continued to organize for the same civil and human rights they had been fighting for throughout U.S. history. As the Black Power movement grew, efforts turned toward the development of the Black Arts Movement, the election of Black officials and the building of Black institutions like Black labor unions.

- Major civil rights organizations had national reach. Some of the NAACP’s oldest and most active chapters were in cities outside the South. CORE shifted its emphasis from organizing in the South to prioritizing work on housing, jobs and police violence in cities across the country.

Influence on Intersectional Liberation Movements

7. Intersectional liberation movements developed within and alongside the Black freedom struggle and other movements for political equality and self-determination were influenced by the strategies of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

- The successes and strategies of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s influenced other justice and equal rights movements in the United States, including but not limited to efforts to secure fair treatment for farmworkers; the American Indian Movement (AIM); and movements for disability, gender and LGBTQ+ equality.

- The Civil Rights Movement and the fight for LGBTQ+ rights intersected in many ways. Several prominent members of the movement were also important voices in the struggle for LGBTQ+ equality.

- As the Civil Rights Movement continued to work toward improving the daily conditions of life for Black people across the country, some activists created separate feminist movements to address the specific concerns of Black women, including the sexism they faced within and beyond the Civil Rights Movement and the racism they faced from white feminists.

International Connections of the Civil Rights Movement

8. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s both influenced and was influenced by other international freedom movements.

- Many activists in the Civil Rights Movement were influenced by Mahatma Gandhi’s principles of nonviolent direct action and by the anti-colonial and liberation movements happening in India, Africa and other parts of the world.

- The Cold War played an important part in presidential decisions to pursue civil rights legislation. Images of violence against protestors in places like Birmingham, Alabama, hurt the image of the United States as it held itself up as a model for democracy abroad.

- In response to disproportionate Black representation among draftees and growing anti-colonial solidarity, some members and organizations within the movement spoke out against the United States involvement in the Vietnam War.

The Movement’s Influence on Cultural Traditions

9. The Civil Rights Movement influenced cultural traditions in the U.S., with artistic and spiritual expressions reflected in and produced by the movement.

- From its beginnings, the Civil Rights Movement was deeply influenced by poets, novelists and playwrights dating back to the Harlem Renaissance and earlier.

- Jazz, blues and the culture that surrounded them created communities where innovative African American thought could thrive. African American spirituals and folk and gospel songs were equally important to the growth and development of the movement. Singing “freedom songs” was a part of many organizing campaigns and mass demonstrations.

- Directly inspired by Black Power and the call for self-determination, the Black Arts Movement brought together artists who wished to create politically engaged work based on the Black experience. The Black Arts Movement is widely credited with inspiring similar movements among artists of other ethnic identities.

The Movement Continues

10. The Civil Rights Movement continues to shape policy, law and culture through the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

- Along with judicial successes like the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, the hard-won legislative victories of the 1960s democratized many American institutions. The strategies and achievements of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s expanded the electorate, reduced organized racial terror by vigilante groups, created new social and cultural organizations and institutions to combat white supremacy, and addressed other forms of discrimination.

- However, despite these achievements, racism and white supremacy persist in the United States. Housing segregation continues, and schools are more segregated now than they’ve been since the 1970s. Structural racism continues to manifest in systems and institutions in many ways.

- Profound economic inequalities continue to exist, stemming in p art from racist hiring and promotion practices. These result in wage disparities and tremendous wealth inequality between white people and Black, Indigenous and other people of color. White households also inherit more wealth, due in part to homeownership made possible by racist laws and policies.

- Political inequality also endures. In the 2013 case Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court overturned some of the most important protections of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. States across the country began passing laws that restricted access to the ballot. Today, Black, Indigenous and other people of color are disproportionately affected by gerrymandering, purges of voter rolls, stringent voter identification requirements and the disenfranchisement of people with felony convictions.

- Mass incarceration continues to devastate communities of color, whose members are imprisoned and processed through the criminal justice system at rates far exceeding those of white people, with lasting consequences for political and economic participation. Police violence, racial profiling and intimidation are routine for many Black Americans, who struggle to find redress in the legal system.

- School segregation remains a significant problem today, and the legal strategy developed by the NAACP in the 1940s and 1950s is still being used to fight for well-funded, integrated schools in district courts across the United States.

- This work toward equality and justice is ongoing, and today many movements fighting economic injustice and police violence trace their roots directly to this era.

- Much of today’s public debate around Confederate monuments and place names can be traced directly back to the popularity of Lost Cause mythology in the period immediately following early civil rights gains for Black people.

- The Black Panther Party’s strategies of community support and self-sufficiency continue to inspire organizers and activists. In 2020, mutual-aid and bail-out organizations developed across the U.S. for community members to support one another through protests and the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s continues to overlap with and inspire other movements. Intersectional protests are a strategic tactic for collective liberation.

- International connections were once again made visible in 2020 with protests in support of Black lives, both in the U.S. and around the globe.