Public school students in the United States today are the most racially diverse in the country’s history. Embracing this diversity can assist us in building a healthy multiracial democracy. In addition, surveys and research have consistently demonstrated that the majority of parents and caregivers in the U.S. support honest education that is inclusive.

A close examination of the current push by lawmakers—especially in legislatures with hard-right affiliations—to censor teaching about race and racism and to attack student-inclusive education reveals a pattern of weaponizing classrooms and curricula to serve an extremist political agenda. In the article “Centering Diverse Parents in the CRT Debate,” Ivory A. Toldson, Ph.D., points out that “some politicians are focusing on ‘parents’ rights’ to disrupt efforts to create more equitable and inclusive education environments. … This insidious strategy normalizes prejudiced white parents, casting them against phantom teachers who are ‘indoctrinating their children.’”

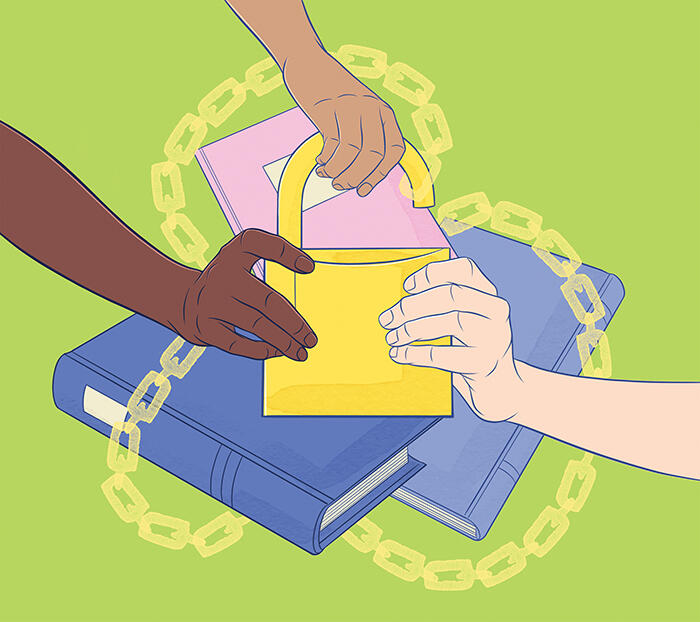

An artificial division between parents and educators is being exploited to advance the harmful agendas of political groups attacking inclusive learning in public schools to the detriment of young people’s well-being and education.

Most parents and caregivers—and responsible family and community groups—in the U.S. support education based on credible well-researched pedagogy, want learning that develops young people’s critical thinking, and favor confronting the challenges of inequitable structures so all children can grow and develop as future decision-makers and citizens.

The Rise of Anti-Student Inclusion Groups

The current increase of so-called “parents’ rights” groups rose from resistance to mask and COVID-19 vaccine mandates in schools, when groups of people using disinformation campaigns intensely and vocally opposed policies to protect students and their families from an ongoing pandemic.

Parents and caregivers do not and should not have the privilege of using their “feelings of discomfort” and their personal beliefs to censor the education of all students, especially through policies and practices that are discriminatory and cause harm.

Simultaneously, the 2020 murder of George Floyd led to widespread attention on diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), which some parents, politicians and hard-right groups quickly labeled as offensive and taboo topics. Battles against DEI were subsequently expanded to include a hyperfocused lens on critical race theory (CRT), which in these cases referred simply to teaching about Black history and culture (not the complex, university-level academic framework of that name). Eventually, these attacks spread and efforts to suppress members of the LGBTQ+ community ramped up. In addition to race, gender identity and expression are now hot-button topics in many schools and communities.

In the past few years, a small group of vocal people have formed anti-student inclusion groups across the country to address what they see as “parents’ rights” issues in education: Black history and conversations about race and racism, along with LGBTQ+ acceptance and inclusive curricula and pedagogy. In addition to attacking students—as well as educators and parents and caregivers—based on race and sexual identity, these groups are ultimately attempting to censor, weaken and politicize public education.

Kevin Myles, deputy director of Programs & Strategy for the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Learning for Justice program, points out that the connection between education and democracy reaches back to the Reconstruction era following the Civil War, when Black Codes specified how Black people would be educated and what they could be taught. And similar to the days following the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Supreme Court ruling in 1954, when preserving the separate and unequal way of life became paramount for some, the descendants of anti-integration groups now seek to continue oppressing students from communities that have been historically excluded from representation. These so-called “parent groups” are not in a battle to protect all parents and students as they would have the public believe. Once again, they are striving to protect white, straight, cisgender history and culture.

Another major goal of anti-student inclusion groups is to curtail the education that Black and other students of color need to advocate for themselves and their communities—Black history, for example. Removing these essential curriculum components and banning books by writers of color limit what young people learn and know about their world.

“If you can change what the next generation learns, you can manipulate the context with which they understand their own conditions,” Myles says. “You can stop the next Black Lives Matter.”

Moms for Liberty leads the pack of anti-student inclusion groups. The group formed in 2021 to protest COVID-19 mask mandates in public schools, and its rhetoric quickly evolved to include anti-LGBTQ+ language, particularly hate-filled speech about gender identity and gender-affirming care. The organization also takes stances against CRT and social emotional learning (SEL) and supports abolishing the U.S. Department of Education. Through their claim of “protecting” children and families, these anti-student inclusion groups produce discriminatory practices that purposely disregard the well-being of young people.

Contrary to their narratives, these vocal so-called “parents’ rights” groups are not and have never been disenfranchised. Parents and caregivers have always had the right to direct their children’s learning according to their own values outside of public schools. They do not and should not, however, have the privilege of using their “feelings of discomfort” and their personal beliefs to censor the education of all students, especially through policies and practices that are discriminatory and cause harm.

Furthermore, in the fight to protect “parental rights,” particularly in schools, those most affected are the students. The inclusion, representation and well-being of all young people are at risk from recent education censorship driven by the opinions of a few with extremist views.

Since the start of 2023, over 400 anti-LGBTQ+ bills relating to education and health care have been introduced in state legislatures. Those directly subjugated are LGBTQ+ students who must endure hateful rhetoric and narratives and are deprived of needed school resources like safe zones and counselors. Similarly, thanks to the urging of the same vocal discriminatory groups, the number of local, state and federal bills introduced to ban CRT has reached almost 700 since UCLA School of Law began tracking these bills in 2020. Students have had their history and identities stripped from libraries and classrooms simply because anti-student inclusion groups define these topics as “CRT.” Moreover, students from other historically marginalized groups—like those with disabilities—also suffer greatly from the consequences of attacks on social justice education programs. And for those young people who share intersecting identities targeted by these policies—such as Black and Brown LGBTQ+ students and those with disabilities—these attacks can compound and cause even more devastating harm.

Of the 2,571 instructional and media books challenged in 2022—a 38% increase from 2021—an overwhelming majority were penned by people of color or members of the LGBTQ+ community. This is a movement of targeted censorship that directly disadvantages students from all demographics by depriving them of complete, accurate education that reflects the world and the nation in which they are citizens.

Identifying the Real Concerns About Education

Although anti-student inclusion groups claim to empower parents to defend their parental rights, they represent neither the rights of all parents and caregivers nor the well-being and educational needs of all students. However, there are organizations and people who are genuinely fighting for the freedom to learn for all students and for the rights of all parents and caregivers.

Organizations like PAVE (Parents Amplifying Voices in Education) and the Baton Rouge Alliance for Students are actually making their actions match their words in working hard to represent their entire communities.

Adonica Pelichet Duggan, who founded the Baton Rouge Alliance for Students in 2021 at the height of COVID-19 and a wave of hostile school board meetings, says the organization tries to drown out the noise from anti-student inclusion groups and focus on the real problems facing parents and young people. “The challenge is that we have a real literacy crisis in our city and also across this country,” Pelichet Duggan says. “And that’s the thing that we all should be waking up with our hair on fire about.”

Like Pelichet Duggan, Maya Martin Cadogan formed PAVE when she noticed a gap between the real issues that families cared about and the educational policies being enacted that impacted families in predominantly Black areas of Washington, D.C. With the goal of conveying parents and caregivers’ educational concerns to lawmakers and those responsible for creating policies, she has engaged dedicated families to become involved every step of the way, including in writing the business plan, mission and vision statement: “Parents are partners and leaders with schools and policymakers to develop a diversity of safe, nurturing and great schools for every child in every ward and community.”

Sometimes issues identified by parents and caregivers are in direct conflict with rhetoric pushed by anti-student inclusion groups. For example, while certain anti-student inclusion organizations rage about the evils of SEL, Martin Cadogan says that the parents involved with PAVE identified SEL as a focus area in 2018. “Our parents are pushing for SEL and mental health,” she says. “Other groups who are pushing against it are the ones that are getting most of the attention.” Additional needs identified include equitable funding for schools and providing students with access to more books, not fewer.

With its Youth Voice Initiative, the Baton Rouge Alliance for Students has also expanded its attention to student-identified needs. “If you want to know what kids are experiencing, they will tell you exactly what they need, what they see that’s a problem, what they see that’s broken,” Pelichet Duggan says. This effort involves working with the Mayor’s Youth Advisory Council and other community nonprofits to engage over 500 teenagers across the city through surveys and focus groups. Pelichet Duggan says that the results serve as a call to action “around what young people are telling us that they actually care about. This is their experience with equity across the city. This is their experience with a lack of mental health supports.”

Supporting Families and Students

Learning for Justice is also seeking to empower parents, caregivers and young people with its newly launched advocacy program, currently being piloted in Houma, Louisiana. The four components of the program are designed to inform parents and caregivers of their rights, teach them to advocate for themselves and their children, build capacity in them to seek positions on school boards, and educate their children on how to advocate for issues that they’ve identified.

Kevin Myles, who leads the program, says that when selecting communities, he is looking for those that face challenges but that also have on-the-ground infrastructure already in place, such as networks ready to step in and support parents and students. He says the goal is to empower parents to take the lead once the groundwork has been laid.

When establishing this program, Myles was careful to consider that the educational issues drawing national attention are not necessarily the priority of local school districts. He invokes psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory to explain, saying, “In a Maslow sense, there are some immediate needs that parents have to take care of before they can get to stuff like bans and curriculum. And that’s a hard pill to swallow.” Parents in storm-ravaged Houma, for example, identified six priority areas that they would like to see improved, including the actual physical conditions of schools, which are affecting their children’s health. Progress in these priority areas will be used to measure the program’s success in their community.

Staying Focused

In 2022, school board elections garnered increased national attention, with many anti-student inclusion groups, political action committees and elected politicians endorsing candidates to solidify their anti-democratic platforms.

In contrast, PAVE and the Baton Rouge Alliance for Students participated in local elections by encouraging parents to run for formal office to advocate for all students, as well as working to foster diverse, nonpartisan candidates who will serve in the best interest of all students.

Both Pelichet Duggan and Martin Cadogan contend that their main fight is not against individual anti-student inclusion groups but against the spotlight being put on them. Pelichet Duggan says, “The people who are often the loudest voices are not engaged with the needs of what parents and families are facing in our community.”

Parent and caregiver advocacy for equitable and quality education is not a new concept. In an era where anti-student inclusion groups are aiming to erode democracy, public education and civic engagement by restricting what students learn—thus preventing them from acquiring the skills needed for responsible participation in democracy—true parent advocacy groups are keeping their focus on the genuine issues plaguing public education.

Resources

The Year in Hate & Extremism 2022

By the Southern Poverty Law Center

“Centering Diverse Parents in the CRT Debate”

By Ivory A. Toldson, Ph.D.