Editor’s Note: This blog was first published at www.Ready4Rigor.com on Feb. 5, 2013 and posted here with permission.

It happens every February. Yep, Black History Month. Some folks are asking if we should even have a Black History Month. That’s neither here nor there, but there are some things to avoid if this annual commemoration is to have any significance. Here are five guidelines I think we should take special care to follow:

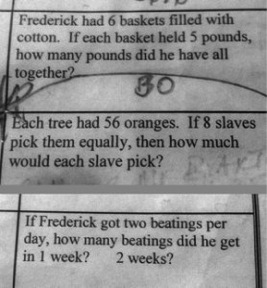

1. Don’t create “culturally responsive” lessons by simply changing the names or circumstances in math word problems, as teachers at Beaver Ridge Elementary School in Georgia did.

Here’s an example of what not to do:

(Remember: Colleagues don’t let colleagues create offensive lessons.)

If the goal is to improve students’ performance by helping them relate to the task, changing names and circumstances doesn’t make a math problem easier to solve.

Instead, take a page out of The Algebra Project’s playbook: Use regional culture as a familiar and friendly reference point in understanding mathematical concepts, not racial history.

To make the concept of a number line more accessible, for example, teachers lead urban students on a field trip on a subway. Students later reconstruct their journey, using a map that represents the number line and illustrates quantity, direction, positive and negative numbers, equivalence and other key concepts.

2. Don’t simply focus on famous firsts or popular celebrities.

When I was in school, we always talked about Dr. Mae Jemison, the first black female astronaut in space, and tennis player Arthur Ashe. By the time my children were in school, the big emphasis was on sports figures like Earvin “Magic” Johnson and Michael Jordan. Nowadays, entertainers and rappers are in the black history spotlight. You can bet that we will be hearing the story of Beyoncé’s early struggles. And, of course, President Barack Obama has replaced Colin Powell as the most prominent black man in American government.

I know we all want to believe we are doing something more sophisticated in our classrooms. But, but by and large, we are still doing some version of what activist and educator Enid Lee calls “heroes and holidays.”

Rather than focus on famous firsts, shake it up and use Black History Month as an opportunity to highlight the often-unacknowledged contributions that people of color make every day: bringing urban farming to inner-city food deserts, for example, or parents of color leading education-reform efforts in major cities like Detroit and Los Angeles. You need not look any further than advertising to see how innovative and creative aspects of black youth culture have been leveraged to sell everything from cars to laundry detergent.

3. Don’t whitewash history (pun intended).

Despite our country’s movement toward becoming a multicultural, multiracial, multilingual society, we still tell a sanitized version of American history. Traditional historical narratives, written from a particular viewpoint, often eliminate, distort or minimize the circumstances and conditions experienced by people of color in this country.

So flip the script. Use BHM to simply ask: Whose story does our history book tell? What other versions of this American story do we need to include, reframe or magnify? Need some ideas for how to do that? Check out the resources offered by the Zinn Education Project. This initiative is named for historian and activist Howard Zinn, author of The People’s History of the United States and A Young People’s History of the United States. He dedicated his life to telling the American story often omitted from the mainstream narrative.

4. Don’t make the month an African-American “mashup.”

Kids at our school bring in soul food and make kente mats out of construction paper. We arrange for guest speakers who are role models, and plan a mish-mash of traditionally Afrocentric activities. This is another reminder for us to move beyond the “heroes and holidays” approach to multicultural education and cultural responsiveness.

Rather than simply going for the additive approach in which African-American themes and perspectives are sprinkled atop the existing curriculum, take this opportunity to restructure your curriculum a bit. Engage students in seeing concepts, issues, themes and problems from different points of view. Pick a focus and go deep with it.

5. Don’t think you can’t talk about black history because you’re a white educator.

Last week at a retreat, a colleague told me how she and another mutual friend lead a professional development session for a multiracial group of teachers in Michigan. She laughed that they were two white ladies talking with this group about race. Well, isn’t it appropriate, I thought, that our white colleagues would be taking the lead in discussions about race? Remember, discussion of anything racialized is not the sacred territory of only people of color. Nor does a discussion about race in America require the presence of a person of color.

I know white educators who are very skilled at talking about race and equality inside the classroom, in the teacher’s lounge and in the community. But they wait for permission or feel the need to apologize for stating the obvious: that we live in a racialized society. (Note: There’s a difference between a racialized society and a racist society. That’s a discussion for another day.)

You do not need to be a person of color to talk about race. But you do need to be comfortable in your own skin, build your knowledge about the topic and be in alliance with educators of color for support and feedback. Remember what happened at Beaver Ridge Elementary. Wonder who their alliances are?

There are a number of white educators to look to for both inspiration and information. I lean on them for insight and understanding, too.

Check out the work of Herb Kohl and his essay “I Won’t Learn From You” in his book by the same name. Then there is Tim Wise, who takes racial awareness to a whole other level. I love the work of writing teacher Linda Christensen and the way she creates a classroom culture that makes it OK to racialize language arts topics. Her books—Reading, Writing and Rising Up: Teaching About Social Justice and the Power of the Written Word and Teaching for Joy and Justice: Re-Imagining the Language Arts Classroom—are both worth reading. Two other good resources are Everyday Anti-Racism: Getting Real About Race in School and Colormute: Race Talk Dilemmas in an American School, both by Mica Pollock.

Now a question for you: How has your teaching of black history changed over time?

Hammond is an educator and writer passionate about teaching and learning. She lives in the San Francisco Bay area. She’s worked as a research analyst, high school and college writing instructor, a literacy consultant, and, for the past 13 years, as a professional developer.