I have loved history all my life; it was my favorite subject in school. Yet, like most students, I viewed most events that occurred before my birth as ancient history. The 1929 stock market crash, for instance, was a topical relic when I was in ninth grade. I could learn the key points and talk about how it led to the Great Depression, but it didn't feel real to me.

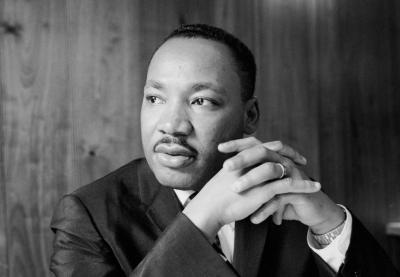

Do students in 2018 feel the same way, I wonder, about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.? Do they merely know the key points of his message, recall a few salient facts about his death and, like my student-age self, fail to see how real he was—and remains today?

On April 4, 1968, I was nearing the end of seventh grade and watching television in my family's living room when the news broke into prime-time programming to announce that Dr. King had been shot. I rushed down the hall to my parents' bedroom to tell them.

The scene played out all too often over the next few months. In June, I woke them to report that I'd just seen Robert F. Kennedy lie bleeding in Los Angeles. In August, I kept them updated about the police riot during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

That year marked a turning point in my life. For the first time, my views of events diverged—significantly—from those of my parents. I had a political awakening in 1968. After Chicago, particularly after hearing Julian Bond's speech, I was on fire against the Vietnam War. That was my activism. I knew of King's work, but racial justice wasn't my first cause.

Over the years, I've witnessed Dr. King evolve from a dangerous man to a secular saint in the public mind. The campaign to honor him with a national holiday began when I was in high school and achieved its goal when I'd already been teaching high school for four years. During his life, the adults around me either ignored or criticized him. By the time President Ronald Reagan signed the bill creating the national holiday, he'd been transformed into a person universally admired for his message of love and peace, and for his stands against bigoted villains like Eugene "Bull" Connor with his dogs and firehoses.

King is remembered for the power of his words, especially "I have a dream," which has become shorthand for all that he stood for. But the real King had a tougher message. He believed that words have power only when individuals are willing to act. For King, acting came at a cost: His home was bombed, he was jailed, he was surveilled by the FBI, his life was threatened and, eventually, he was killed.

As for his message, this winner of the Nobel Peace Prize cherished more than a vision of small children living in racial harmony. King understood that racism stood alongside war, militarism and poverty as scourges to justice. His mission after Selma and the passage of the Voting Rights Act was to fight against the Vietnam War and call for the eradication of poverty.

Fifty years after his death, we should all be asking, "What would Dr. King be marching for now?" I think he'd be proud to know that many of the legal obstacles to equal opportunity have fallen, and terribly saddened by the ways our society is still unjust and our opportunities unequal.

I think that the man who preached, "God never intended for one group of people to live in superfluous inordinate wealth, while others live in abject deadening poverty," would work to end the wealth gap and ensure that all people have access to health care, a minimum income and adequate food and housing.*

This is, after all, the man who wrote in his final book (Chaos and Community, 1967) that a piecemeal approach to improved education, housing and jobs wasn't the way to end poverty. Instead, he wrote, "I am now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective—the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed matter: the guaranteed income."

Of course, that matter is no longer "widely discussed." What's being discussed instead are mean-spirited policies that would make Ebenezer Scrooge blush, like denying Medicaid to people who don't have jobs.

I also think about the man who said that "a nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual doom." Would he look at the $80 billion defense budget, at law enforcement agencies equipped with military-grade gear, at schools with armed guards and metal detectors, at our 15-year-long war in Iraq and at the thousands of wounded veterans and think that our society has already arrived at spiritual doom?

Would he stand for any of it? Or would he keep pointing out that all of these—war, poverty, incarceration, gun violence, ill health, poor housing, substandard education—fall disproportionately on people of color?

In 2018, if we are to honor all that Dr. King stood for, the question isn't "What would Dr. King march for?"

The question for each of us is, "What am I marching for?"

When you commemorate Dr. King's life on the anniversary of his assassination, share his righteous anger at poverty and militarism. Understanding that he was an actual person with human emotions can move students past the sanitized, whitewashed version of King and help make his legacy real for youth today.

Costello is the director of Teaching Tolerance.

*1963, "Strength to Love" speech.