Teaching 'The New Jim Crow'

Preparing to Teach 'The New Jim Crow'

In The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander introduces readers to the phenomenon of mass incarceration in the United States and challenges readers to view the crisis as “the most pressing racial justice issue of our time.” In the introduction, Alexander writes: “What this book is intended to do—the only thing it is intended to do—is to stimulate much-needed conversation about the role of the criminal justice system in creating and perpetuating racial hierarchy in the United States.”

Young people need to have a role in national discussions about race and racial justice; participating in these discussions requires that students learn to talk about the relevant issues in meaningful and constructive ways. Yet some teachers shy away from critical discussions about race. This teacher’s guide is designed to provide the resources and support you need to explore these critically important issues with your students.

In reading The New Jim Crow, your students will be asked to engage with these essential questions:

- How does the U.S. criminal justice system create and maintain racial hierarchy through mass incarceration?

- How does the current system of mass incarceration in the United States mirror earlier systems of racialized social control?

- What is needed to end mass incarceration and permanently eliminate racial caste in the United States?

Teaching Tolerance deeply appreciates the work you are doing to prepare a generation of students to be able to talk openly and honestly about the historical and contemporary causes of racial inequality and the actions we can take to better our society. It is critical that we develop the skills necessary to facilitate these types of conversations. No matter our identities, how long we’ve been teaching or how conscious we believe we are, all of us can get better at talking about race, racial inequality and racism—past and present.

What follows are some strategies and methods that can support you as you support your students in this journey. A list of supplementary resources, organized by lesson, can also be found here.

Assessing Your Comfort Level

Conversations about race, racism and other forms of oppression can be difficult. Sometimes we avoid talking honestly about race and racism because we fear conflict or because we feel we do not have the skills and competencies to engage in these difficult conversations. We often fear messing up, sounding like “racists” ourselves or doing harm unintentionally. Part of the work of getting students ready to talk about The New Jim Crow is acknowledging these fears.

One step in strengthening your own ability to facilitate conversations about race and racial inequality is to assess your comfort level prior to beginning the lessons in this guide:

First, on a scale of 0-5, how comfortable are you talking about race and racism?

0 = I would rather not talk about race/racism.

1 = I am very uncomfortable talking about race/racism.

2 = I am usually uncomfortable talking about race/racism.

3 = I am sometimes uncomfortable talking about race/racism.

4 = I am usually comfortable talking about race/racism.

5 = I am very comfortable talking about race/racism.

Another warm-up you might try with yourself or colleagues is a sentence stem activity:

The hard part of talking about racism is …

The beneficial part of talking about racism is …

After self-assessing and reflecting upon your own comfort level, think about how you will stay engaged in the work. Do you tend to reroute classroom discussions when you sense discomfort in the room? Commit to riding the discussion out next time. Do you feel isolated in your experiences with teaching about racial issues? Commit to identifying a colleague with whom you can co-teach, plan or debrief.

Teaching about racial issues requires courage and openness—from you and your students. You will encounter personal discomfort as you deepen your understanding of racial inequality, its causes and consequences. Many of the facts, claims and uncomfortable realities detailed in The New Jim Crow may be new to you and your students. The more you facilitate difficult conversations, the more comfortable you will become with being uncomfortable. The conversations may not necessarily get easier, but your ability to sit with your discomfort and press toward more meaningful dialogue will grow. Stay engaged; the journey is more than worth the effort.

Being Vulnerable

Fear of facilitating conversations with significant racial dimensions can stem from our own fears of being vulnerable. What will teaching The New Jim Crow potentially expose about you? Reflect for a moment and consider revisiting this question as you teach the curriculum.

For now, list three fears or vulnerabilities that you are concerned could limit your effectiveness. Next, identify three strengths you possess that you believe will aid you in facilitating open and honest dialogues in your classroom. Finally, list specific needs that, if met, would improve your ability to facilitate conversations about race and racial inequality.

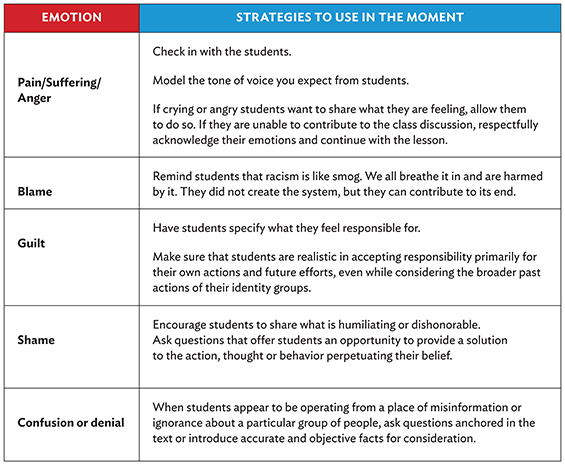

Addressing Strong Emotions

There are multiple ways your students may react to talking about The New Jim Crow. They may react passively, indicate deep sorrow, express flashing anger or respond in a way you would not predict. Some students may become visibly upset; others may wonder why they’re learning about the topics raised in The New Jim Crow. At the root of many of these reactions are a variety of feelings that often emerge during honest conversations about race and racism: pain, blame, anger, confusion, guilt and shame.

Seeing members of your class express these emotions may elicit strong reactions from you or your students. Guilt and shame can result in crying that may immobilize conversation. Feelings of anger might result in interrupting, loud talking, sarcasm or explicit confrontation—all of which can impede important dialogue. Your role when these strong emotions arise is to remain calm and offer strategies to diffuse the situation so that learning can continue.

How can the strengths you listed above calm students and diffuse tension without avoiding or shutting down the conversation? Spend time thinking ahead about how you will react to strong emotions when they arise.

Look at the table below. Based upon your knowledge of your class, consider the emotional responses that might emerge as you teach these lessons. Add additional emotions you think may emerge, and list potential response strategies.

Keeping the Conversation Going

Part of developing skills to facilitate conversations about race with your students is equipping them with strategies they can use themselves. In addition to the strategies above, some pedagogical approaches can help students learn to sit with their discomfort and learn to moderate that discomfort over time. Below are a few approaches that Teaching Tolerance recommends using when teaching the lessons in this guide:

1. Reiterate. Contemplate. Respire. Communicate. (RCRC).

Explain these steps as a method for communicating while feeling difficult emotions. These steps are not intended to move students away from the emotions that reading The New Jim Crow may trigger, but instead to be a tool to help them self-regulate as they experience those emotions.

- Step 1: Reiterate. Restate what you heard. This step will enable students to reflect upon what they have heard as opposed to what they think they may have heard. Repeating what they have heard limits miscommunication and misinformation.

- Step 2: Contemplate. Count to 10 before responding. Students can think about their responses and use the time to compose what they want to say. Taking the time to think about their responses moves students away from immediate emotional responses that can potentially derail the conversation.

- Step 3: Respire. Take a breath to check in with self. Suggesting students breathe before responding may help them settle their thoughts and emotional responses during difficult conversations.

- Step 4: Communicate. Speak with compassion and thoughtfulness. Students should do their best to speak to their peers as they want to be spoken to, assuming good intentions and seeking understanding. Explain that, when they disagree with something someone has said, they should focus on challenging the statement rather than the person who said it.

2. Check in with students.

Discomfort with opposing or new ideas is normal and something we need to learn to sit with. You may be able to increase comfort by establishing a safe space within your classroom, built upon the trust and mutual respect you and your students hold for one another. It is important to note, however, that for some students—particularly students who are members of marginalized, nondominant or targeted identity groups—you may not be able to provide complete safety. It is also true that an overemphasis on identity safety risks reducing the diverse realities of our students’ lived experiences in and outside of school. In addition to providing nurturing, safety and comfort for your students, build their resilience and strength so they are more willing to take the risks involved with feeling uncomfortable.

In order to stay on top of feelings of safety, risk, trust and comfort, it is important to monitor the emotional temperature in the classroom and check in with students about how they are feeling. This awareness will assist you in knowing when to stop and address strong emotions students may be experiencing. Checking in nonverbally to gauge students’ comfort levels allows all students to participate without being singled out or put on the spot. Try some of the following ideas:

- Fist-to-Five. You can quickly gauge a number of things—readiness, mood, comprehension—by asking students to give you a “fist-to-five” signal with their hands:

- Fist: I am very uncomfortable and cannot move on.

- 1 finger: I am uncomfortable and need some help before I can move on.

- 2 fingers: I am a little uncomfortable, but I want to try and move on.

- 3 fingers: I am not sure how I’m feeling.

- 4 fingers: I am comfortable enough to move on.

- 5 fingers: I am ready to move on full steam ahead!

- Stoplight. Use the colors of a traffic light to indicate student readiness and comfort. Throughout the lesson, you can ask students if they are green, yellow or red. Students can also utilize the “red light” as a way to request a break or a stop when they are feeling strong emotions or have been triggered.

- Green: I am ready to proceed.

- Yellow: I can proceed but feel hesitant about moving forward.

- Red: I do not want to move on yet.

3. Allow students time and space to debrief

Everyone engaged in an emotionally charged conversation needs support systems in place to allow for the safe “discharge” of residual emotions. Students may have thoughts or questions that arise once they have left your classroom. Provide them with the opportunity to debrief what they are learning and their experience of learning it. Depending on your group, you may want to devote a portion of each lesson, half a class period or an entire class to debrief and reflection. Two strategies are listed below:

- Talking Circles. Gather in a circle and create, or review, the norms that will help build trust in the Circle. Select an object of significance to serve as a talking piece that signals participants to engage equally in the discussion. Whoever holds the talking piece can speak, while the rest of the Circle listens to and supports the speaker. Pose a question or statement to begin the discussion. It could be as simple as, “How do you feel about today’s lesson?” As the facilitator or Circle Keeper, you will participate as an equal member of the group. As students become familiar with the process, consider inviting them to be Circle Keepers.[1]

- Journaling. Personal reflection through writing can be extremely effective for debriefing after difficult conversations. Journaling can help students process their emotions on their own terms and at their own pace. Journals can be kept private or can serve as a space where you dialogue with students by writing back and forth.

[1] Amy Vatne Bintliff, “Talking Circles for Restorative Justice and Beyond” tolerance.org/blog/talking-circles-restorative-justice-and-beyond