Graphic novels have come into their own in the publishing world—and from a critical literacy standpoint, it’s well deserved. Unlike their more traditional text-only counterparts, contemporary graphic novels trend toward diverse voices and stories, and in the past 10 years the market for these stories has skyrocketed. Nearly every traditional publishing house is seeking to add graphic novels to its list. As a result, publishers are seeking a greater variety of stories and voices from talented but lesser-known authors who might not have been picked up otherwise. This trend is good news for educators who care about social justice. A teacher wanting to expose her students to diverse perspectives and narratives could do no better right now than to look toward graphic novels.

Graphic novels are also slowly escaping the stereotype that they are picture books with no value to literacy instruction. Their new status opens avenues for more educators to realize that these texts can be taught using nearly the same approaches as any other book, fiction or non. Even most state and Common Core English Language Arts and literacy standards can be taught via graphic novels. They can be used in nearly every subject and are particularly valuable as counter-texts in social studies and ELA classrooms.

Young adult author Laura Williams McCaffrey teaches graphic novels as texts in her ELA classes at an alternative middle and high school in Vermont and also includes them as part of her curriculum in a masters of fine arts program.

“The discussions contain a lot that we’d consider during discussions of prose,” McCaffrey says. “We examine character development, aspects of plot, theme and real-world relevance. Even the discussions of style and tone relate to style and tone as these are expressed by prose writers.”

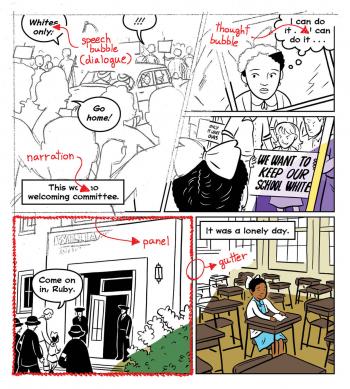

Using graphic novels does, however, require a sophisticated set of skills and understanding of a few basic differences between illustrated and all-text narratives. Setting, pacing, and story structure are largely the same, but the units used to tell the story differ. Words can be either dialogue or narration. Images are divided into panels, which are separated by gutters laid out strategically on the page.

McCaffrey also notes several examples of opportunities graphic novels offer to focus on visual literacy. “We might discuss repeated images that become symbols over the course of a story. We might also discuss visual style. What is the difference between the style Gene Luen Yang uses and [that of] Marjane Satrapi or Art Spiegelman? We might discuss stylistic contrasts within a text. In addition, we discuss the relationships between aspects of the story that are relayed through words and aspects relayed through images.”

The narrative of a graphic novel is carried by images instead of words. Readers often have to infer what has happened during the transition from one panel to the next, a cognitive leap referred to as “closure.” Effective use of graphic novels in the classroom helps students analyze how authors juxtapose images to create moments of closure.

Worth a Thousand Words

One of the main difficulties with teaching literacy standards to English language learners and other students who are not reading at grade level is that the texts they can read are generally not complex enough to meet the appropriate standards. But these students can read much more sophisticated graphic novels because the brunt of the storytelling burden lies in the pictures. A high school student, for instance, with no written English proficiency at all can analyze theme, structure, character and point of view in a complex graphic novel like Shaun Tan’s critically acclaimed The Arrival. In fact, the only Common Core ELA-Literacy standard he could not study with that book is standard RL.6.4: “Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in the text.” The Arrival is wordless. And because there are so many quality international narratives and stories from different cultural perspectives, they are often more directly relevant to the experiences of English language learners.

Because closure requires a high level of reader participation, the emotional impact of graphic novels can be quite high. Particularly if the student is reading about something outside his realm of experience, such as the civil rights movement, closure can generate reader empathy for the characters in the story. This makes graphic novels especially valuable to social justice educators who want to provide their students with windows into multiple identities and experiences. This approach is an extension of contact theory: Research indicates that exposure to diverse voices and experiences can reduce in-group/out-group prejudices, even when the exposure occurs through reading.

As with comic books, graphic novels’ smaller cousins, the dramatic impact of these visual texts lends itself to subject matter related to struggle, conflict, injustice and other highly emotional topics. (See examples like Maus by Art Spiegelman, The Wall by Peter Sis, American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi.) Depending on the artist’s intent, the story might be depicted literally or veiled as an allegory or a counter-text alternative to more traditional narratives. In any event, social justice content may be both empowering and unsettling for young readers.

“[Graphic novels] contain powerful images, some of which have been used in the past as stereotypes or slurs,” says McCaffrey. “The presence of these images in the stories forces readers to confront them and discuss them. … The stories also include visual representations of protagonists we don’t always see represented as protagonists.”

Reading and teaching graphic novels through a critical literacy lens offers opportunities for students to question the text and make meaning of images and of characters who, as McCaffrey points out, they may not be used to seeing as protagonists. In this way, the genre draws on the history of zines, historically created and distributed through grassroots efforts to inform and empower specific audiences. In some cases zines—and even commercial comic books—have been used to spread subversive images and messages aimed at undermining powerful or unjust entities, as in the case of the classic underground comic book Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, which served as a nonviolence primer for African Americans in the deep South during the 1950s. This text is also a primary source, an artifact of history that played an active role in furthering the civil rights movement.

Another way to extend the learning benefits of teaching graphic novels is to let students create their own. This is the approach that Chris Slakey, an ELA teacher at De Vargas Middle School in Santa Fe, New Mexico, takes through a partnership with the Santa Fe Art Institute (SFAI). According to Nicole Davis, an education program associate with SFAI, the project started to help students become more aware of the issues that affect their own lives and neighborhoods.

“A large majority of De Vargas kids deal with a lot of everyday racism,” says Davis. “Last year, we had a student who wrote his entire graphic novel about a man who lives in his neighborhood and yells racial slurs at the children when they play outside. When this student shared his project with his peers, a majority said they had their own stories of racism or xenophobia.”

The potential for transformation is not lost on Slakey. Although many of his students are reluctant to talk about their own experiences with injustice, the opportunity to tell their stories through graphic art allows them to change the power dynamics surrounding their negative experiences. “They can … talk about things they’ve been through, but through the creation of these other characters,” says Slakey. “It allows them a shield.”

Watts is a writer and educator based in in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

A Modern Classic

In August of 2013, Congressman John Lewis, a lifelong human rights advocate and civil rights activist, released March: Book One, the first volume in a trilogy of graphic novels detailing Lewis’ experiences at the forefront of the civil rights movement. It was a surprise smash hit, debuting at number one on both The New York Times and The Washington Post bestseller lists.

More importantly, however, March has quickly captured the imaginations of thousands of young readers and become a critical resource for educators seeking creative and engaging materials to deliver the history of the civil rights movement into the hands of students.

March: Book One spans Lewis’ youth in rural Alabama, his life-changing encounter with Martin Luther King Jr., the birth of the Nashville Student Movement, his arrest at a nonviolent sit-in protesting a segregated lunch counter and builds to a stunning climax on the steps of Nashville City Hall. In its creation, Lewis drew from his memories of Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story and how it helped prepare his own generation to study nonviolence and join the struggle for civil rights.

Lewis intentionally continues this legacy by using graphic art to bear eyewitness to one of our nation’s most historic struggles. His writing is personal, the drawings are vivid and dynamic, and the message powerful and provocative. Says Lewis about his motivation for writing March, “We wanted to make it plain, clear and simple for another generation to understand, not just my story, but a story of a long and ongoing struggle to bring about justice in America.”

The Washington Post declared, “Lewis’ gripping memoir should be stocked in every school and shelved at every library.” It is well on its way. March: Book One has already been taught in over 30 states at the postsecondary level with several schools adopting it as common reading for all students. Teachers at the middle- and high-school levels also report that their students eagerly dive into the visual narrative of March and learn critical literacy skills and civil rights history at a level of depth and sophistication not offered by most traditional textbooks.

As identified by Teaching Tolerance, all nine of the essential areas for civil rights education (events, leaders, groups, history, obstacles, tactics, connections to other movements, current events and civil participation) can be found within the pages of March. The book’s themes—equality, citizenship, agency and collective action—are more than just lessons of history. This vivid rendering of Lewis’ story stimulates both robust learning about the past and critical thinking about current and future events, making March a powerful and urgently relevant title for today’s classrooms.

March: Book One was co-authored by John Lewis and Andrew Aydin and features the art of Nate Powell. A free teacher’s guide is available at the Top Shelf Productions website. Look for the release of March: Book Two this month!