On Aug. 28, 1963, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, during which Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, drew a crowd of more than 250,000 people from across the United States. The march has become one of the most iconic events from the Civil Rights Movement. Contextualizing the march and the complex history of the struggle associated with it is important as we make connections to the ongoing movement for equality and justice.

Key Concept:

As the Civil Rights Movement grew, local and national organizations and grassroots groups employed a variety of methods, aims, philosophies and strategies to achieve their goals, including an expanded emphasis on direct action.

Background of the March on Washington

Veteran civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph first put forward the idea for a march on Washington in 1941, during World War II, to address employment discrimination. That march didn’t happen because the threat of a march on the National Mall during the war pressured President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802, which banned discriminatory practices by federal agencies and national defense industries. The idea of such a march, however, remained an important strategy for visibility and galvanizing the Civil Rights Movement.

The 1963 March on Washington was initiated by Randolph, who brought together a coalition of major civil rights organizations: the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Urban League, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Conference of Racial Equality (CORE), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The goals of civil rights and desegregation were combined with the demands for economic justice.

Key Concept:

The Civil Rights Movement and the fight for LGBTQ+ rights intersected in many ways. Several prominent members of the movement were also important voices in the struggle for LGBTQ+ equality.

Learn More:

Learn about the life and work of Bayard Rustin, a critical contributor to the movement and an openly gay man. The Throughline podcast episode “Remembering Bayard Rustin: The Man Behind the March on Washington” is a great place to start. You can also read the Henry Louis Gates Jr. article “Who Designed the March on Washington?” (available from PBS) and watch the short PBS Newshour video clip “The Story of Bayard Rustin, Openly Gay Leader in the Civil Rights Movement.”

Organizing the March

Bayard Rustin, a close associate of Randolph’s and an adviser to Martin Luther King Jr., planned and handled the details of organizing the march. Rustin was an experienced civil rights activist and organizer who believed deeply in the power of nonviolent protest. As an openly gay Black man, Rustin faced discrimination, both in society and in the movement, over his sexual orientation.

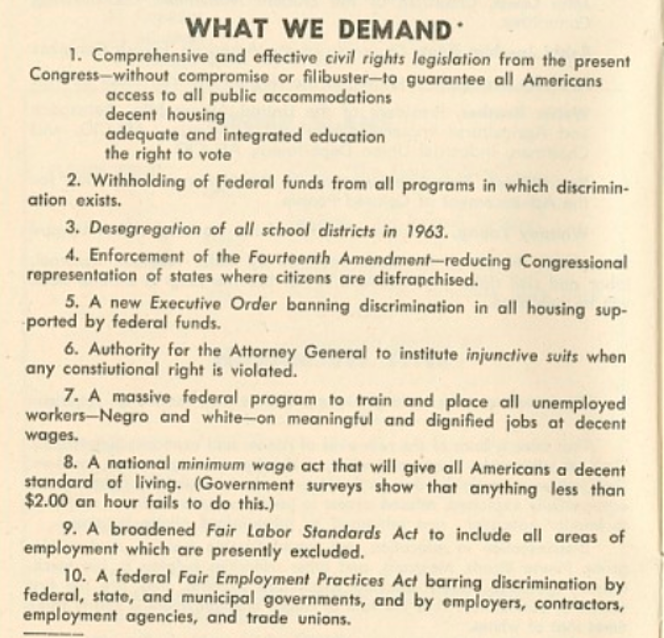

Rustin and his organizing team produced the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Organizing Manual, which laid out the philosophical reasons for the march and the goals along with all the practical details for the event. The section “What We Demand” lists the 10 goals of the march, which ranged from demands for legislation to ensure civil rights, access to housing, integrated education and voting; to enforcement of protections against discrimination; to programs for job training, national minimum wage and expanded protections in employment. Economic justice was a foundational demand for the march from Randolph’s initial planning.

Learn More:

To understand the range of issues that brought people to the March on Washington, review photographs to see the signs the marchers carried. The LFJ text “Dr. Martin Luther King Marches on Washington” offers a good example.

“The March on Washington” page from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund provides valuable resources, including the work of strategist Bayard Rustin and links to the march’s various speeches.

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

That summer day at the National Mall shines a spotlight on the strategy of marches and protests to draw attention to the movement.

The march was a high point for many, bringing together people of different races in support of civil rights. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech was inspiring in eloquently giving an affirmative vision of American democracy. While Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech is the most famous from the march, it is important to remember that the march was not King’s work alone. Along with King, speeches by John Lewis (representing SNCC), Randolph and other male leaders of the major civil rights organizations are often remembered to mark the historic day.

Even though the March on Washington drew a crowd of a quarter of a million people, some people and organizations in the movement dismissed it as ineffective. They argued that while the event helped build white public support for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it did little to influence congressional votes or to support events on the ground in the freedom struggle. Others have credited the march with helping increase visibility for the movement and adding pressure that resulted in civil rights legislation. Historical analysis will continue, and so too will the lessons learned from the march and the strategies of the organizers.

Learn More:

The Speech interactive pages available on the Guardian’s website provide more context regarding the lead-up to and aftermath of the march.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture’s collection The Historical Legacy of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom includes primary source documents to explore as well as analytical articles and short videos of some of the speeches, including from the march.

Watch the video of “John Lewis’ Historic Speech at the March on Washington” (available from NowThis News on YouTube) and/or read the transcript. At the march, John Lewis presented a censored version of his original speech. For deeper understanding, you can read the original version of Lewis’ speech, “Patience Is a Dirty and Nasty Word,” and compare it to the speech he gave.

Women Civil Rights Leaders: Missing Voices

The movement was much more than the March on Washington and the vision of the men who were on the program to speak that day. In thinking about the more complex history, the march is insightful in what was missing that day – the perspectives of women leaders in the movement.

Women movement leaders such as Dorothy Height and Anna Arnold Hedgeman worked to help organize the march and raised concerns about the limited presence of women in the program. Talented leaders and organizers, like Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker, for example, were not included as speakers.

Key Concept:

As the Civil Rights Movement continued to work toward improving the daily conditions of life for Black people across the country, some activists created separate feminist movements to address the specific concerns of Black women, including the sexism they faced within and beyond the Civil Rights Movement and the racism they faced from white feminists.

Learn More:

To learn about women leaders of the movement, the PDF “Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement,” from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the SPLC article “Women of the Movement” are good starting points.

Learn about Fannie Lou Hamer at PBS’s American Experience, Freedom Summer article series. Read about Ella Baker at the New York Historical Society Museum collection Women and the American Story and watch the short video Women You Should Know: Ella Baker from the National Civil Rights Museum.

Historical Context: Events in 1963

Finally, several significant events surrounded the march, marking 1963 as a year of dramatic change in the United States. Knowing about key events of 1963, both before and after the march, can help us contextualize the time and the march.

Learn More: Events in 1963

April – Martin Luther King Jr. writes “Letter from Birmingham Jail” after being arrested in Birmingham, Alabama

May – Children’s March in Birmingham, Alabama

June – Fannie Lou Hamer and movement activists are arrested and beaten in Winona, Mississippi

June – Medgar Evers is assassinated in Jackson, Mississippi

August – March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Washington, D.C.

September – Bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church kills four young girls, Birmingham, Alabama

November – President John F. Kennedy is assassinated, Dallas, Texas

Learning and reflecting on the March on Washington amid this history encourages us to not simply examine famous historical moments in isolation but to consider them in all their complexity and historical context. By doing so, we are encouraged to keep learning more and to connect lessons from the past to challenges of the present.

In exploring the March on Washington and its context in the Civil Rights Movement, we can learn both from the organizing strategies and strengths and from the challenges and missing voices at the march.

Reflection and Action

1. Reflection: “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

Fannie Lou Hamer’s powerful words, “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free,” remind us that in the movement for freedom we are connected to the struggles of others. Why is it, therefore, important to recognize the absence of women like Hamer from 1963 March on Washington?

We must not only advocate for justice for issues that affect us personally, but for those that affect others in our communities and our nation.

- Think about the issues and civil rights concerns in your communities. Consider the ones that affect you personally or to which you feel strongly connected. Then think about issues that do not affect you but for which you can be an ally.

2. Inclusivity in Justice Movements

Read “Confronting Ableism on the Way to Justice” by disability rights activist Keith Jones, who reminds us that to build a society that advances the human rights of all people requires the social justice movement to be intentional in including intersecting identities and diverse equity struggles.

- Consider how you can help ensure that work for justice and equality in your community is inclusive of diverse voices and perspectives.

3. Election Recommendations: Believe that Change Can Happen

You cannot strengthen democracy with cynicism. Believe that change can happen. Disillusionment and despair are tools for voter suppression. Those who wish to disenfranchise you want you to think your vote doesn’t matter – so that you do not exercise it. No matter the election, never forfeit your vote. Your participation can help bring about the change you seek.

Youth Learning for Justice

1. Writing Across Time

Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” is one of the most well-known and powerful writings from the Civil Rights Movement. Write a letter to the leaders and activists of the movement, or to a specific individual, discussing where things stand now in your lifetime. How have the issues changed or stayed the same? How will you build on their work to address these injustices today?

2. Women of the Civil Rights Movement

Research some of the women leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. Write some key points that they might have discussed during the 1963 March on Washington, had they been given the opportunity.

3. Activity: Reflections Over Time

Watch this clip of Dr. King reflecting, in May 1967, on his “I Have a Dream” speech and the 1963 March on Washington and sharing his thoughts on how he sees things four years later.

- In what ways have Dr. King’s beliefs changed and stayed true to the message in “I Have a Dream?” What events have caused him to revisit his thinking?

- Dr. King says, “That dream that I had that day has in many points turned into a nightmare.” What does he mean? Explain why he concluded that “We still have a long, long way to go.”

- How can we connect Dr. King’s famous speech and his later reflection to events taking place in society today? Can you give examples that fit his dream and his reflection that there was still work to be done to achieve the goals of the movement?

- Discuss Dr. King’s point about the impact of ongoing war in U.S. society. How is this point still relevant in society today?

Growing Together Series

We Have a Dream: The March on Washington

This overview of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom includes activities to help young children and families make connections to history, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, and the children’s story “The Night Before the Dream.”