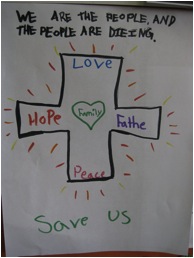

A plea from students.

A plea from students. Editor’s Note: This month, Teaching Tolerance launched a new series of lessons called Issues of Poverty. This week’s featured lesson can be found here.

Nearly 14 million children live in low-income or poor families in the United States.

One of those was Devin.

He had been in my English class during my first year teaching. His uniform was old and faded. He (like 95 percent of the school) was eligible for free or reduced lunch. He didn’t have much in the way of supplies. It was unclear if he really didn’t have the materials, or if he simply didn’t care.

He was not talented in the types of test-driven work that schools have become in the business of assigning. He was boisterous, rambunctious and silly. After a build-up of misbehavior and classroom outbursts, he was expelled.

A few months later, he was shot in the back of the head. It occurred a few houses down from where he lived.

This is what I think about when I think about poverty.

At his funeral I ran into a few of my former students who had also been expelled. One student was rumored to have been the target of the shot that killed his friend.

They weren’t bad kids. They were just growing up in a tough neighborhood. Money and worldly experience were scarce. The path that school was trying to steer them onto (success through homework and sitting quietly in class) wasn’t cutting it.

While we were struggling to prepare them for our reality, these boys were living in a totally different one: a reality where young folks around them made lots of money with drugs and violence. It’s amazing they complied with school as much as they did.

It was good to see my former students alive, healthy-looking, supporting each other through this difficulty. In eighth grade, these kids were 16 and 17 years old and living in a dangerous neighborhood. They had every reason to be frustrated. Having written a few of the referrals that resulted in their eventual expulsions, I was surprised when they greeted me with hugs. It was obvious that the politics of school didn’t matter now.

During the funeral, there was happy music. A mother spoke. Devin’s little sisters were dressed in yellow dresses with matching hair ribbons. The boys were decked out in alligator shoes. People shouted “amen.” The pastor reminded us that in heaven the streets are lined with gold.

Devin’s open-casket funeral was the first I had seen. I had never before glimpsed a dead body. What a privileged life I’ve lived. Few of my students could say the same.

On the way back, I asked my students Rhade and Samia, both 14, how many funerals they had attended. Each shook her head with a sort of ain't-that-a-shame eyebrow arch. There were too many to count.

I was 23 at the time. I had only been to two funerals.

There’s more than just the inequality of money and physical resources in the gap between the haves and have-nots. More pressing and persistent in the lives of our poor students is the inequality of death. It hits them much more often.

And those kids—Rhahde and Samia, all of Devin’s siblings and cousins and classmates and friends—they have to go to school again the next day. If they’re lucky, there might be a social worker or counselor on campus, but those roles are dwindling, as the top-down focus becomes more about testing than mental health.

Even if we cannot change the circumstances outside of our classrooms, we can remember them.

The National Center for Children in Poverty reminds us that the number of adolescents who live in families whose income places them below the poverty line is increasing. Now, more than before, we must remember to respect our students as we encounter them in class, and also, the lives that our students bring with them.

Craven is a middle school English teacher in Louisiana.