I have often heard that phrase, “the courage to teach,” and dismissed it, thinking it referred to nothing more than long hours, discipline problems and exhaustion.

But as my teaching career progresses, I have realized that “courage” really means learning to live in a state of disequilibrium. It means covering topics and delving into feelings that might easily be avoided. I have found that the deepest learning happens in those uncomfortable places. If our goal is to create life-long learners with the skills necessary to become critical thinkers, to challenge prejudices and to develop compassion, we must provide opportunities that foster this type of character building. This often means that we, the teachers, must get outside our own comfort zones.

For the past nine years I have included a disability awareness unit in my social studies curriculum. I did this in part because of my own childhood experiences with a mother who used a wheelchair. I remember the way children would sometimes stare at her, dying to ask questions, while their mothers dragged them away insisting that they must not speak to her.

I could see the pain this kind of avoidance caused my mother, yet I often sympathized with the moms who didn’t want to confront my mother’s disability. To be frank, I too was distressed by the changes polio had made to my mother’s body. I found it hard not to shrink back when I saw her paralyzed legs and feet. I regularly found myself making a conscious effort to lay those uncomfortable feelings aside and see beyond my mother’s body.

As a teacher, I wanted to share my journey with the children in my classroom and give them a chance to learn what I’d learned. I wound up learning just as much from my students as they learned from me.

I wanted to provide a setting where my students could ask questions about disabilities, and people with disabilities could answer back directly. So I called several organizations serving people with disabilities, and invited members into the class to share. I didn’t just want my students to know that many kinds of disabilities exist. I wanted them to see that although these people’s bodies sometimes look different, their feelings, hopes and dreams are similar to my students’ own.

Our first visitor was Miguel, a young man who was studying to become a graphic designer. Before his visit, my students practiced hard to be able to communicate with him in his language — American Sign Language. Despite their preparation, my students were surprised by the uncomfortable feelings that arose within them hours before our visitor was to arrive. Many admitted that they were scared to meet a Deaf person.

We talked about how the unfamiliar can be frightening, even when it is neither bad nor wrong. This visit led them to look inside themselves, where prejudice lives. Gradually, my students’ anxiety faded as they got to know Miguel. Following his visit, they became diligent in their sign language practice, determined to communicate well with the next Deaf person they met.

In order to give my class a sense of life as it is experienced by people who use wheelchairs, I rented a few wheelchairs for the class to use. Students stayed in the chairs all day, including recess, to see how others treated them, and to experience the difficulty of maneuvering through the school. It took time for them to see that the chair was not a toy. Then one student cried out, “I hate having people look down at me or not look me in the face.” We had entered the uncomfortable zone, a powerful place where real learning occurs.

Soon our next visitor, Daniel, arrived. Daniel, then 26, had been in a diving accident in his teens, and had used a wheelchair ever since. After their own experiences using wheelchairs, my students wanted to know the details of Daniel’s life. How do you take a bath? Do you have any friends? Do you ever get frustrated and want to give up? They were exactly the sort of questions that other children, long ago, had wanted to ask my mother. My students took it all in, and wrote moving and insightful essays about their experiences.

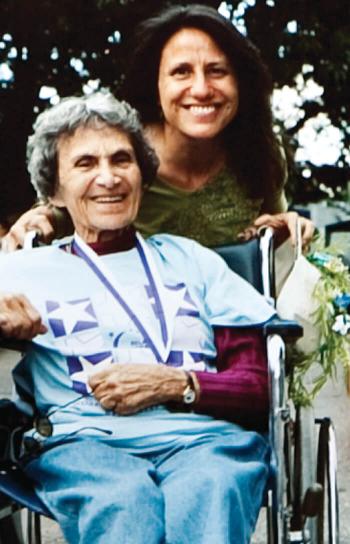

My mother was our final speaker. This time I noticed my own fears rising. More than with any other visitor, I wanted my students to see the person, not the disability. I worried that they would react to her body fearfully.

As I wheeled her in, the children were silent. I had prepared them through discussion, research and books on the history of polio and its effects. Wide-eyed, they circled around, ready to hear her speak.

In a shaky voice she began talking about her life and how she contracted polio. She described what an iron lung was and told about the overriding fear that gripped the world as the disease spread. She talked about being made to feel different from other people, and about the challenges in her life. Then she lifted her pants leg to reveal her paralyzed leg and brace, explaining all the scars from numerous operations. I flinched, fearing that children were going to go home with horrific stories of their teacher making them look at her mother’s disgusting paralyzed leg.

But nothing of the sort happened. On the contrary, students asked if they could touch her brace and wanted to know in detail how it worked. Questions came steadily until the recess bell rang. Instead of running out of the room, they argued over who was going to push her chair out to the playground.

In teaching about people with disabilities, I expected messiness. I did not think that along with my students, I too would be brought to a place of disequilibrium — a place where I would need to re-examine my own deep-seated feelings. My students’ unrestrained enthusiasm for my mother reflected back to me all that I had withheld from her. I had never asked her how her brace worked, or if I could touch her leg. I had always been too busy trying to soften others’ stares and protect her from hurt, not trusting her resilience.

As I learned then, and have learned anew whenever my mother comes into my classroom, there is nothing to fear. My mother’s face exudes joy as she shares the hardships and successes of her life, while my students, focused and attentive, show her that she is valued.

It really does take courage to teach — to guide students through issues that are challenging not just for them, but for the teacher as well. This is where both student and teacher can be transformed.