First-grade teacher Carol Myers has taken numerous elementary classes on field trips to the Muncie Children’s Museum in Muncie, Indiana, but the fall 2013 trip was different.

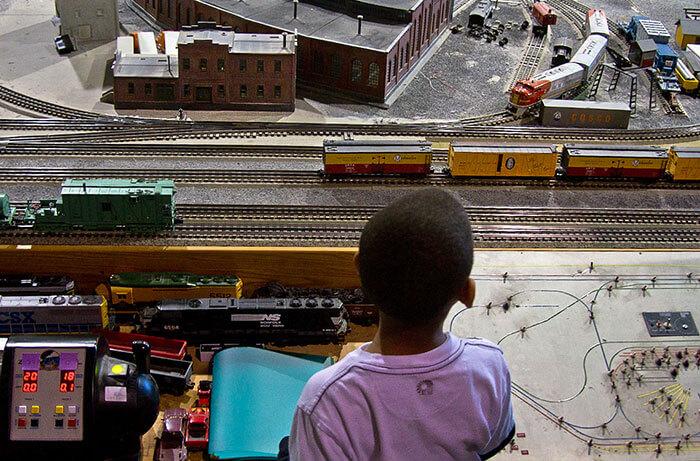

While half the first-grade class attended the museum’s program on fire safety, the other half freely explored the museum, including the popular train exhibit that depicts the town of Muncie in miniature. It was upon examining the figurines in the exhibit that 6-year-old Madisyn Jones noticed something amiss. The typically quiet little girl turned to her student teacher, Brooke Forler, and asked, “Why aren’t there any black people in the train exhibit?”

Forler looked more closely at the figurines. “I pointed to a figurine of a darker complexion and said, ‘Do you think that one could be African-American?’ [Madisyn] said, ‘No, it doesn’t look like me,’” said Forler. “And then I said, ‘Well that’s a problem, isn’t it? So let’s see what we can do about that.’”

True to her word, Forler consulted with Myers—her mentor teacher at the time—and her Ball State University education professor, Eva Zygmunt, about how to proceed. The three educators wanted to engage the entire class in a lesson that would respond to Madisyn’s observation but were concerned the children wouldn’t understand the social justice implications. They were wrong.

Later that week at the majority African-American Longfellow Elementary School, Forler told the first-graders about what had happened at the museum and asked how they felt about it. The robust discussion that followed didn’t take much prompting from the teachers. While none of Madisyn’s classmates had noticed a problem with the exhibit, they agreed with Madisyn’s perspective.

“They said things like, ‘Yeah, we should be able to see ourselves in the train exhibit because it’s not fair that I can’t see anybody that has my skin or someone that looks like me,’” Forler explained. “We discussed that, if we’re not okay with something, it’s perfectly fine to raise questions about it and try to make a change.” The lesson culminated in the class working together to write a letter to the museum voicing their concerns about the lack of diversity in the exhibit and offering to help rectify the problem.

“We were excited that they took those steps to work with the community, help us out and share the story,” said Jennifer Peters, director of exhibits and education for the museum. “It’s such an important story to tell.” Thousands of people have viewed the display since the museum’s train exhibit opened in 1996, but no one had ever mentioned that it was not representative of Muncie’s population. Madisyn’s 6-year-old eyes had seen something that so many adults had not noticed.

The keen sense of justice and injustice Madisyn demonstrated is a quality of early childhood many educators nurture successfully, engaging children in first grade—and even younger—in social activism. It starts with listening and sending the message that all voices matter and everyone can make a difference—just as the Longfellow Elementary teachers did when they helped the first-graders write their letter.

With the museum’s enthusiastic support, Forler and her colleagues began the search for representative figurines. It was a tough journey—and one that reinforced the importance of the project. They began with a search of local stores, including the original supplier for the train display, but found no figurines of color at all. They were prepared to order blank figurines and paint them when Zygmunt came across a promising set of advertised figurines online. What they found on opening the set was unacceptable, to put it mildly. “All the African-American figurines, except for one, were part of a prison set, wearing orange and working out in a yard,” lamented Zygmunt. The only nonprisoner was stealing a woman’s purse—another dead end.

Then one of Zygmunt’s colleagues, a train enthusiast, caught wind of the story and pointed the team to a company that produced figurines that worked. The selection featured tiny people of color engaging in various recreational activities and wearing a variety of clothing, including business attire. Finally, the teachers were ready. The museum was ready. It was time for the first-graders to finish the job they had started.

The class returned to the museum in February 2014, bursting with excitement. On her seventh birthday, Madisyn placed the first figurine in the display. All the mini-members of the Muncie diorama, she said, could be happy now that their new neighbors had arrived.

By speaking up and taking action, Madisyn and her classmates became part of a story they may never forget. Peters has already witnessed two of the students telling others about what happened at the museum, and Myers notes the experience has prompted some of Madisyn’s other “quiet” classmates to become more outspoken in class.

The experience has changed Madisyn, too. “It just really opened Madisyn up,” Myers reflected, “and she’s very vocal now—maybe too much sometimes.”

Myers acknowledges it’s not always clear how to tap into the activist natures of young students, but her experience taught her the importance of adults who support children’s desires to act and their abilities to think deeply and critically about the world around them.

“Appreciate the depth of kids’ knowledge,” she said. “Be open-minded and talk to them.”

To help her students draw a connection between what happened at the museum and the broader world of social activism, Myers taught her class about another young girl who spoke up.

“The best way I could explain it to my first-graders was that Madisyn was our Ruby Bridges,” Myers explained. “Just saying that really helped these kids understand what Madisyn had done. She wasn’t just complaining; she noticed something that really did need to be changed.”

The similarity is not lost on Madisyn.

“We both spoke up,” she said, “and we spoke the right things.”

Teaching Tolerance Resources on Activism

Inspire your student activists!