Walking through the halls of Bonita Vista High School in Chula Vista, California, it’s clear the school and its students have a message to send: Hate has no place here.

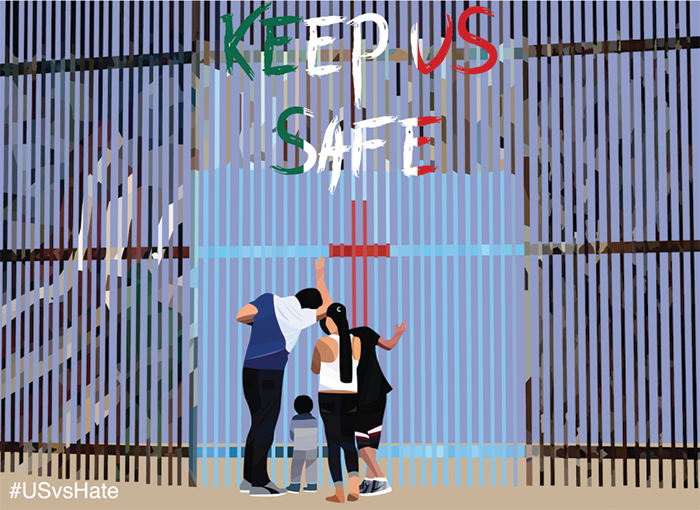

The classroom windows and bulletin boards display posters with slogans like “Stand strong for others” and “Humanity is bigger than borders.” Students’ binders and water bottles are plastered with stickers declaring, “When you fight for equality, fight for everyone.”

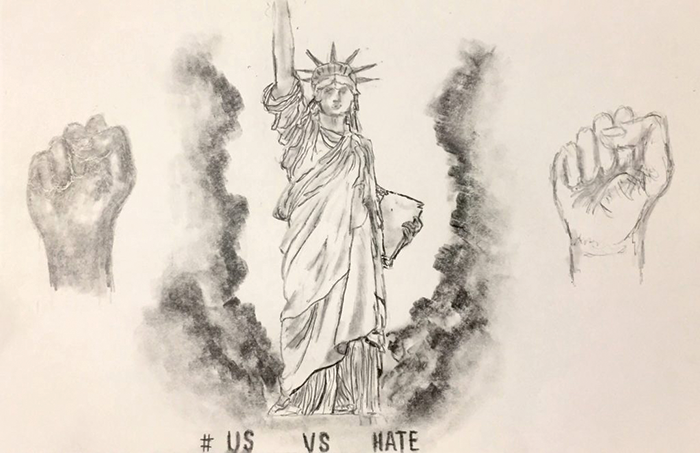

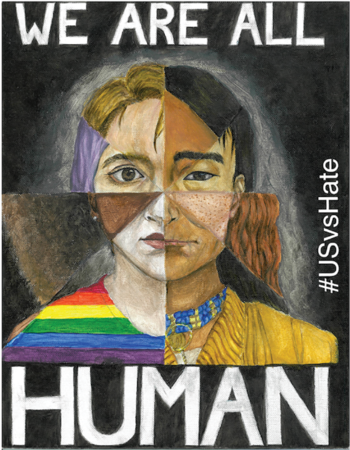

It’s not just the tone that distinguishes these posters and stickers from typical hallway decor; although they are professionally produced, the artwork was made by students. These inspiring words aren’t being forced on kids by adults. They are messages to young people from young people.

A few years ago, these messages weren’t visible at Bonita Vista. They later appeared as part of a multi-district curricular intervention called #USvsHate, which originated out of the UC San Diego Center for Research on Educational Equity, Assessment and Teaching Excellence (CREATE). Mica Pollock, a professor at UCSD and the director of CREATE, describes #USvsHate as “a vehicle for young people to engage the issues of our time and to publicly put forth their perspective and proactively message against hate.”

“This is an initiative that invites student voice,” says Pollock, who led the design of the #USvsHate pilot in collaboration with San Diego educators, UC San Diego doctoral student Mariko Cavey and CREATE Digital Specialist Minhtuyen Mai. “Kids are given an invitation to message and speak their perspective. Teachers are being invited into a collective effort to work on the issues of our society rather than pretend the world doesn’t exist.”

Kalie Espinoza, a veteran 10th-grade English and International Baccalaureate teacher at Bonita Vista, was part of the development team that piloted #USvsHate. Like many of her fellow educators, Espinoza had seen a spike in anti-immigrant hostility after the 2016 election and felt a growing sense of hopelessness after the deadly Unite the Right riot in Charlottesville, Virginia. Chula Vista is part of the San Diego metropolitan area that sits at the border between the United States and Mexico. Seventy percent of her students are Latinx.

“We’ve had students chanting in the hallways, ‘Build a wall!’ We’ve had students make comments in classes, in passing,” Espinoza says. “I’d had a couple of years to get familiar with the community before the election, and seeing that uptick … was really disappointing.”

Espinoza was one of 10 educators from across three San Diego school districts originally recruited to co-create #USvsHate with Pollock and other members of the CREATE team. The goal: Support teachers and students in resisting hate—at school and beyond—by offering an easy-to-implement curricular option that resulted in authentic, sharable, student-driven work.

The intervention consisted of four steps:

- Select and teach anti-hate lessons based on local needs.

- Ask students to create anti-hate messages based on their learning.

- Share the messages across the school and publicly.

- Extend the learning by asking, “What’s next?”

The team launched a website to support the project. It houses the lesson portal, the professional development (PD) resources, and a platform for teachers to share students’ artwork and even enter it in a messaging contest. Contest winners and finalists are shared online, and a subset of messages are produced as free posters and stickers for participating classrooms.

Patrick Leka of San Diego High School joined the #USvsHate pilot as a relatively new teacher without much experience discussing racism and other types of bigotry with students. He decided to start with an anti-bullying lesson he felt confident he could implement, then gradually moved into more challenging topics as he gained more knowledge, in part by accessing the PD materials on the #USvsHate website.

“Once you get your toe in the water, it allows you to feel comfortable exploring other areas that are really important to your students,” says Leka, who teaches ninth- and 10th-grade English and AVID. “The most exciting thing for me was just to know and feel from [students] that we’re doing something that is a direct, real-world connection for them.”

Espinoza agrees that the success of #USvsHate is fundamentally tied to student engagement. Part of that success was due to the lessons she chose—activities and readings about refugees, immigration and other topics that directly affect her students’ lives (all aligned to the Common Core, the Teaching Tolerance Social Justice Standards and her district’s instructional standards). Another part was the opportunity for students to have their messages and artwork reproduced and to know that students across multiple districts would see it and vote on their work as part of the contest.

“I definitely found students become more empowered,” Espinoza says. “They were so excited with their work; they were very proud of it and happy to have other people see it, and they were shocked when they went to the website and were like, ‘Oh, my work’s on the website?’ [It] was a really cool thing to see them celebrate that.”

Over the course of the pilot, Espinoza and Leka both observed their students becoming more thoughtful in their discussion of identity and less inclined to make insensitive jokes or comments. In interviews and surveys throughout the pilot, students, too, reported their attitudes changing. One 10th-grade student said about observing their peers’ work, “It makes you think, ‘When someone was working on this, what were they thinking? Why were they doing this?’” Said another, “Seeing it physically in the classroom, especially because [the] poster is right in front of me every day, you can just have that reminder of how to be more open-minded to certain topics, especially if they cause controversy.”

For Leka, participating in #USvsHate didn’t just engage his students and improve his school culture; he says it made him a more courageous teacher.

“It’s something that now I’m planning on doing every year for the rest of my career,” he says. “I’m planning a unit right now for the novel Night, and I went right to the #USvsHate website to find things that tie into what’s going on today with antisemitism and how can I talk to my students about that. It’s something that I don’t necessarily have experience with myself, but I now feel more prepared to talk about it.”

van der Valk is a former Teaching Tolerance staff member and currently serves as the communications director for the Center for Genetics and Society.

Art (and Competition!) as Inspiration

Posters and stickers weren’t the only media through which students communicated their anti-hate messages. As the project grew—eventually expanding to educators in more than a dozen districts—so did the opportunities for students to make, share, view and vote on different forms of art.

“I had a student do a seven-minute-long spoken word this year, and every single one of my classes wanted to hear it. I’ve had students who have made videos, who have written speeches, who have written poems. Some of the schools have done performance art or a comic book,” says Kalie Espinoza, adding that, from a curricular point of view, the expanded options allowed her to teach about how to match message to medium. “It was such a quality piece of learning alongside the social justice aspect of it.”

Sarah Peterson and Kim Douillard are the regional directors for the California Reading and Literature Project and San Diego Area Writing Project, respectively. They both encouraged teachers in their networks to participate in the pilot, witnessing firsthand the power of the contest and how voting on messages extended the opportunity for students to use their voices.

“[Teachers] heard about it, they had tons [of] examples, the kids had started seeing lots of images by voting, and they were telling each other about it. It was pretty neat to see,” Peterson says. “I’m just thinking of a video of a teacher that I work with in my network. When her students won, it was as if they won the lottery. She took a video of them learning that they won—they were screaming.”

That teacher later reported to Peterson that winning the #USvsHate messaging contest had been a turning point for her classroom.

“I hope for more kids to be screaming and excited and pumped to share their messages and read the messages of their peers around the nation,” she says.