An old American promise supports the importance of the First Amendment: that within a marketplace of ideas, truth emerges from the din. That promise could not have predicted the mass of information now at our fingertips. An outdated metaphor gives way to a present-day challenge. How do we value truth, devalue malicious misinformation and create a new marketplace of ideas?

Beginning on October 31, general counsels from Facebook, Google and Twitter participated in hours of congressional hearings, answering a barrage of questions about how Russians used their platforms to interfere with American political life, most notably during the 2016 presidential election.

In this case, interference does not suggest the manipulation of voting machines. Instead, it meant manipulating U.S. media messages—a nonviolent act of cyber warfare featuring a weapon that has since become a buzzword: misinformation campaigns. These campaigns often fall under the now-infamous phrase “fake news.” Just one source of such campaigns was responsible for nearly 1,000 YouTube videos and more than 100,000 tweets. Facebook admitted that more than 126 million of its users were exposed to misinformation campaigns via ads.

How does fake news become news?

These messages—mostly false and inflammatory—fanned the flames of partisanship and spread fake stories with the intended goal of undermining the election and sowing discord among Americans.

It’s a serious issue. Free and fair elections are fundamental to a functional democracy, and misinformation threatens to dismantle that system.

Despite the importance of combating misinformation and teaching students skills to help them recognize fake news, teachers face a roadblock in broaching the topic: The concept of “fake news” has become politicized—a shorthand for news one finds disagreeable. Such mislabeling falsely equates the Washington Post and Wall Street Journal with misinformation outlets, such as the sites controlled by Macedonian teenagers spreading false stories for profit.

But educators understandably worry about teaching students to identify fake news. By design, misinformation campaigns appeal to extreme ends of the political spectrum, and debunking such stories in class can leave teachers open to accusations of partisanship or bias. Beyond the issue of teacher neutrality, cognitive science tells us that continuing to expose students to fake news will make that story more familiar, and “familiarity casts the illusion of truth.”

Our Digital Literacy Framework offers seven key areas in which students need support developing their digital and civic literacy skills.

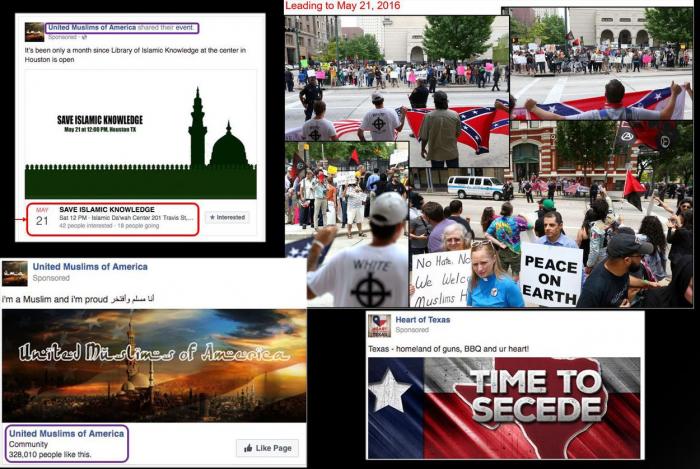

That said, two Russia-linked Facebook ads released as a result of the congressional hearings offer a teachable moment.

On May 21, 2016, two competing ads created by Russian operatives created a protest and counter-protest out of thin air—and Facebook users took the bait. According to the Texas Tribune, two fake, Russian-controlled Facebook groups (one called the United Muslims of America, the other promoting the secession of Texas) amassed hundreds of thousands of followers and used that influence to manufacture what would become a somewhat tense scene at the Islamic Da’wah Center of Houston. People took action based on a lie. Imagine if the result had been more violent?

A story like this allows educators to introduce the topics of misinformation and fake news without fearing backlash. A bipartisan group of congressional leaders released this as an example of dangerous Russian influence, and both sides of the story can be flagged as clearly false. Partisanship does not apply.

Therefore, a class discussion is less likely to enter the realm of “Which story is true?” Instead, students can spend time exploring a more essential question: “How can online users better recognize these attempts to trick and divide people?”

The fact that both narratives came from Russian operatives also opens up a door to talk about U.S. democracy and its opponents. Why is trusted information essential in a democracy? Why might a country seek to destabilize our democracy by planting fake news? How should Facebook, Google and Twitter counter this threat, if they have any responsibility at all? How should students counter it? What actions have students taken as a result of something they’ve seen online?

These questions open up a necessary dialogue and offer a first step toward equipping students with the skills to recognize fact from fiction online, and evaluate the influence misinformation could have on their offline actions and beliefs.

This also opens up an opportunity to teach students about the ways in which social media sites and search engines use people’s personal information to sell targeted ads or posts. This information—including users’ names, political leanings, interests, places they visit, products they buy, religion, sexual orientation, etc.—plays into the hands of misinformation campaigns. Those running the campaigns can specifically target stories to those who would find the fake news appealing, affirming or worth sharing. Such targeting has consequences, and students should know the use of their personal details makes their attention a commodity for ad buyers. Armed with that information, students can cast a critical eye at content geared toward them.

You Are the Product

Explore the concept of “going viral” and how advertisers use social media to promote their products and identify potential customers.

The 2016 presidential election is a lightning rod for teachers—a classroom controversy waiting to happen and tempting to avoid. But Congress’s expressed concern over Russian interference and misinformation online should signal to educators that this is a topic they needn’t avoid.

Today’s marketplace of ideas will have to rely on critical thinking. Without it, truth is relative to the consumer. This is especially true online, where the safeguards against hostile influence, evidently, do not exist. Teachers can hope lessons in critical thinking will extend to online discourse and behavior. Or, conversely, they can use this pivotal moment in our history to tailor lessons to their students’ new, hyper-connected reality. Aspire for the latter.

Our democracy depends on it.

Collins is a staff writer for Teaching Tolerance.