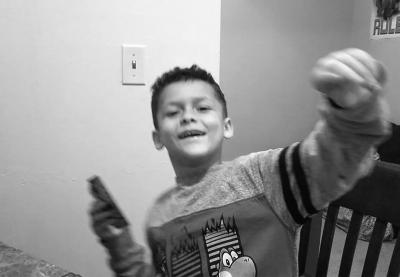

Jamel Myles was 9. He was brave, and he was beautiful, and that phrase—that ghost of a phrase, he was—sticks in the back of the throat.

Because now he isn’t.

Jamel died by suicide last Thursday. But the cause of his death is more complicated than that. Jamel was gay. He came out to his mother this summer. Days into the school year, he confided to his oldest sister that his peers had told him to kill himself. Then he did.

Mincing words feels like wasting time: Our schools aren’t safe. For all of our cultural progress toward LGBTQ inclusion, school climates continue to be plagued by homophobia and transphobia. School climates continue to kill.

According to the Human Rights Campaign’s 2018 LGBTQ Youth Report, only 26 percent of LGBTQ students said “they always feel safe in the classroom.” Only 13 percent had heard positive messages about LGBTQ people in school. Yet nearly three-fourths of them had faced verbal threats or bullying or both because of perceived or actual LGBTQ identity.

Our school climates are part of the reason lesbian, gay and bisexual kids consider suicide at triple the rate of their straight peers. They’re part of the reason why 40 percent of trans adults say they attempted suicide—almost all of them before the age of 25.

Whether you work with elementary, middle or high school students, in traditional or alternative settings, there is a student just like Jamel Myles in your school. In your classroom. In your circle of influence. Think of them now: Are they in the minority of LGBTQ students who always feel safe at school?

Are you sure?

A safe space poster sends a beautiful signal, but it can’t follow them through the hallways, onto the bus and online. A better school culture can.

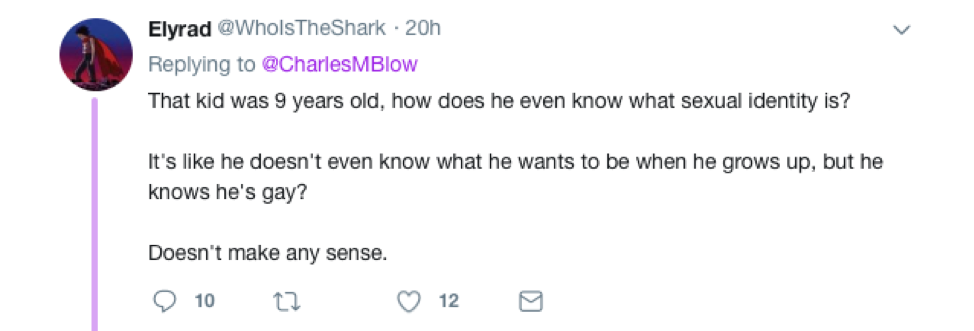

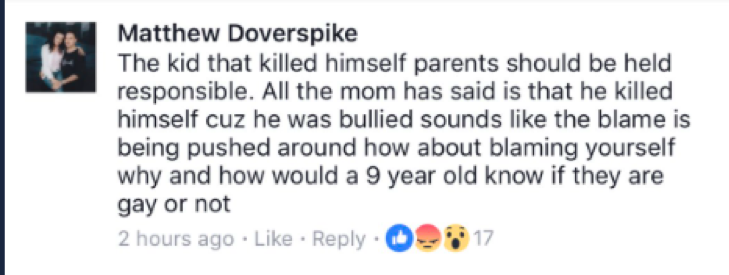

When Jamel’s story went viral, people rushed to the comments to question how a 9-year-old child could possibly know he’s gay. The answer is simple: Experts indicate that people experience same-sex attraction at grade-school age, often before reaching sexual maturity or awareness. But the question itself reveals a bigger problem.

It shows us that even the death of a child won’t silence the drumbeat of heteronormativity. And underneath that noise is another: the clatter of homophobia. We hear it when we talk about a third-grade boy “crushing” on a girl in class but then label two boys who are inseparable as “best friends.” We hear it when we don’t blink twice at a baby boy or toddler in a shirt reading “chick magnet” or “future ladies’ man,” but we insist that a 9-year-old can’t know his own feelings.

When we say these things, kids hear what we mean: that queerness is for adults. That queerness must be about sex. That queerness isn’t normal. That queerness can’t be innocent.

Every time an educator chooses not to interrupt homophobia, they help cement this idea of what is normal—and what is questionable. Every time an educator contributes to heteronormativity with their classroom activities or their language, they send a message.

Our students are listening. This message lets straight kids know that they are “the normal ones.” And it whispers to queer children that their very identities are an open question, an open debate. It tells them their lives are an afterthought.

Instead of asking how a boy could know he was gay at age 9, we all should be asking why—according to his mother—Jamel already knew to be scared of that truth. “[He] looked so scared when he told me,” she told KDVR-TV. “He was like, ‘Mom I’m gay.’ And I thought he was playing, so I looked back because I was driving, and he was all curled up, so scared. And I said, ‘I still love you.’”

And we know the answer to that question, too. We know why he was afraid.

Stories like Jamel’s motivate our upcoming publication, Best Practices for Serving LGBTQ Students. And students like yours compel us to remind you of the ways in which educators can, quite literally, save lives.

This means taking inventory of school policies. What are the steps your school takes to remind LGBTQ students that their identities are worthy of respect? This preview of our Best Practices guide walks you through LGBTQ-inclusive practices, including exemplary components of anti-bullying and harassment policies. Demand them.

This means taking inventory of your allyship. How deep does it go? These six steps can act as a checklist for you when you want to stand behind LGBTQ students, especially when bad news happens.

This means making sure your students know there is help without heaping shame. How are you ensuring all students have access to this information? Publicly post the Trevor Project’s suicide hotline number, and let students know about the Crisis Text Line.

This means speaking up. When was the last time you actually talked with your students about the effects of biased language and hateful behavior? Silence in the face of homophobic harassment sends a potent message, whether that harassment is happening in your classroom, your school, your district or beyond. Our guide for speaking out against hateful words gives you strategies you can use as soon as tomorrow. And you should.

I was 9—Jamel’s age—the first time I felt butterflies in the presence of a boy. I was 13 and still prepubescent when I stole the fold-out from my sister’s Enrique Iglesias CD because I was “curious about the lyrics” that happened to surround the pictures. But I was in kindergarten when I learned that you don’t hug boys like you hug girls; in first grade when I learned that you give valentines to girls you like; in second grade when I learned that you go to school dances with girls you like; at fourth-grade football practice when I got called a f—t for the first time, for no other reason than the fact that being called gay was the ultimate insult. By middle school, I knew shame better than I knew myself. I knew my parents would love me if I came out, but that school would be a different story. In classrooms, in the hallways, in the locker room, being gay was considered funny at best—and disgusting and dangerous at worst. Only in the far corners of the internet, writing under a pseudonym, did I pretend to be proud.

Jamel Myles was braver than I. According to his mother, “He went to school and said he was gonna tell people he’s gay because he’s proud of himself.” As he should have been.

If only—when the chorus of his peers telling him to kill himself became too much—he had heard an answer to their taunts that was just as loud, that was made of just as many voices, that was just as constant. If only the message had been this: You are valued. You are normal. You can be yourself, without recourse.

Schools can send that message.

So can you.