The 2018 midterm election brought a spate of historic firsts. For women of many identity groups, for LGBTQ candidates and for candidates of color, it was a historic election. And for educators looking for examples of representation and inspiration for students, it’s tempting to build a lesson that’s a list. To put up posters. To point to their names, their faces, and tell our students: “This is progress! Look what’s possible!”

But progress isn’t exponential; it’s incremental. It’s beset by pushback and steps back. Almost 250 years after the Declaration of Independence, some of us are still fighting for the right to vote. And if we don’t teach students the context behind these historic firsts, we’re not really celebrating the breaking of barriers. We’re pretending the barriers were never there.

In her book White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, Robin DiAngelo cautions against using “narratives of racial exceptionality” or narratives that reinforce “ideologies of individualism and meritocracy” when celebrating a historic first. These stories, she says, ignore the institutional and systemic power structures that kept people out—structures that, ultimately, had to bend to let people in.

If we want our students to recognize injustice, we must show them the role it played in these stories. We must emphasize that, yes, each of these people was and is exceptional—but they were not the first to possess the talent, will or work ethic necessary to succeed.

Focusing on power structures means contextualizing these historic firsts, positioning them both at the front of a line of successes and at the end of a line of attempts. It means recognizing a history of almost-change, of stumbles and steps backward, of those whose names we’ll never know, who threw themselves against the barriers and weakened them a little each time.

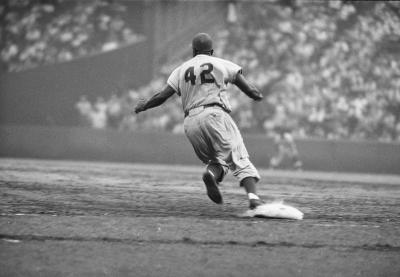

The danger, of course, is that such a focus threatens to undermine the accomplishment and agency of those who finally did succeed in the face of oppression. We wouldn’t want, for example, for a student to walk away thinking that Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier only because the activist work of others led white baseball owners to suddenly shift toward fairness. That’s why, to tell the full story when teaching famous firsts, we have to teach both the “who” and the “why.”

So who was Robinson, the first black man to integrate Major League Baseball? Students may be interested to know he was a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army, court-martialed in 1944 for refusing to move to the back of an Army bus—11 years before Claudette Colvin and Rosa Parks would famously do the same in Montgomery, Alabama. He was an athlete who, as late as 1972, would refuse to salute the U.S. flag because “I am a black man in a white world.” He was—like most who break through barriers—an activist determined to fight for equity. But he wasn’t the most talented black baseball player of his era, or of eras past, nor was he the first to recognize injustice.

Why was Robinson the first black man to integrate Major League Baseball? Walking students through this question means talking about power structures in the United States in 1947. It means discussing how, a decade earlier, Jesse Owens could return from the Olympics to a New York ticker-tape parade—and a party at the Waldorf-Astoria he had to join through the service entrance. It means talking about the tradition of segregation and Jim Crow legislation, as well as those who protested it. It means addressing head-on the racist rhetoric that suggested black players were intellectually and physically inferior. It means discussing the ways the rigid barriers in the dugout mirrored those in American society, and how, like American society, baseball was not as meritocratic as it claimed.

The barrier never truly broke; it bent. The number of U.S.-born black Major League Baseball players peaked in 1981. Today, the increasing economic burden on youth who want to play baseball, among other factors, has locked many black young people out of the game.

When we teach about Robinson—or any other barrier “breaker”—we can both encourage marginalized students with a story of resilience and let them know we recognize historical barriers to equity and the barriers many of them still face. That, in itself, is empowering. It breaks down a myth of meritocracy painting generations of people as lacking in will or effort; it celebrates achievement without diminishing the impact of systemic oppression.

We can’t talk about historic firsts without also talking about the talented ancestors who came before—nor without talking about who built the barrier to begin with. When we mention Sharice Davids’ and Deb Haaland’s historic victories as the first Native women elected to Congress, we should give students the history of Native women leaders—and we should also teach about historic and present-day voter suppression and how it specifically has been wielded against Native populations.

When we tell students Gwendolyn Brooks was the first black writer to win a Pulitzer Prize, we should talk about the challenges that women writers of color in her era faced, the publishing houses that saw little value in black artists; the lack of diversity among those tasked with awarding such honors; and the imagined lack of interest in stories by and about women of color. And we should talk about how those challenges persist today, how book reviewers are disproportionately male (as are authors whose books are reviewed), or how the film industry seemed surprised by the successes of major motion pictures like Crazy Rich Asians and Black Panther.

Here are some questions to try with students:

- Where did this “famous first” fall in contemporary power structures? At the time, which identity groups benefited from privilege? Which did not?

- What systems were in place to maintain the power structures of the time? (Ask students to consider legal systems, but also cultural systems: common use of stereotypes, violence, de facto segregation.)

- How were people fighting against unjust power structures at the time? Which structures were changing?

- What was the impact of this “famous first”? Did their achievement open the door for others—for people who shared their identity group or for those of different identity groups? How quickly was the “famous first” followed by non-famous successors?

With that frame—with a focus on the why along with the who—a list of names and facts can transform into a library of stories about the ways in which power structures have shaped our nation’s narrative, and how we can overcome them. It’s the difference between an inspiring poster and a map. It’s the difference between a path and a guide.

Collins is senior writer for Teaching Tolerance.