My daughters will never attend a school with Negroes so long as there is breath in my body and gunpowder will burn.

Bryant Bowles, an avid segregationist in Delaware, 1954

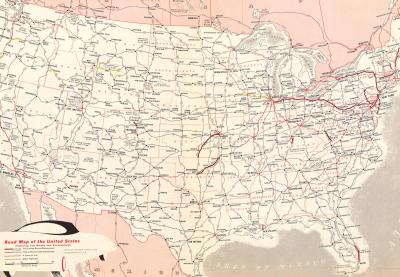

In 1954, 17 U.S. states mandated segregation. These laws affected about 9 million white children and 2.3 million black children in public schools.

Four other states allowed segregation but did not require it.

The remaining 27 (Alaska and Hawaii were five years away from becoming states) either had laws prohibiting segregation or had no laws regarding segregation. In those states, segregation still occurred based not on laws but on socioeconomics and living patterns.

The scene varied from state to state, but the patterns were clear in the South:

- White hospital patients could be tended only by white nurses; black patients, only by black nurses.

- Textbooks used by white students were kept separate from those used by black students; interchanging them was forbidden.

- Even in prisons, white prisoners could not be shackled with black inmates on chain gangs.

James T. Patterson, in Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and its Troubled Legacy, paints this picture of 1950s Kansas, a border state balancing elements of South and North:

Topeka did not impose a color line in the waiting rooms of its bus and train stations or on its buses. Yet five of the seven movie houses barred black people, a sixth was for blacks, and the seventh admitted blacks to its balcony — "Nigger Heaven," it was called. The park swimming pool was closed to blacks except for one day in the year. A restaurant regularly patronized by the white lawyer who was to handle the Brown case on behalf of Topeka featured a sign, "Colored and Mexicans served in sacks only."

In 1954, collective shock over the brutal murder of Emmett Till had not yet galvanized the nation; Rosa Parks hadn't yet refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus; and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech was still years — and worlds — away.