It's late on a mid-May afternoon on St. Helena Island, S.C., and a couple dozen schoolchildren, ages 5 to 12, line up inside Faith Brown's classroom at the Penn Center school in the heart of the Gullah Nation.

The children rehearse what Brown calls the theme song for the Penn Center's Program for Academic and Cultural Enhancement, or PACE. "St. Helena Hymn," by John Greenleaf Whittier, a 19th-century abolitionist-poet, was written for Charlotte Forten, the first African-American teacher hired at the school.

The students sing lines recalling the 1861 emancipation of island slaves:

The very oaks are greener clad

The waters brighter smile;

Oh, never shone a day so glad

On sweet St. Helena's Isle.

The PACE curriculum stresses the ancestral history of the Gullahs' African roots, promotes environmental awareness and — because Sea Island folks have always liked to grow their own food — even shows the kids how to plant and tend a garden.

"I love what we do, that we integrate their own culture with everyday academics," Brown said.

Heart of a 'Nation'

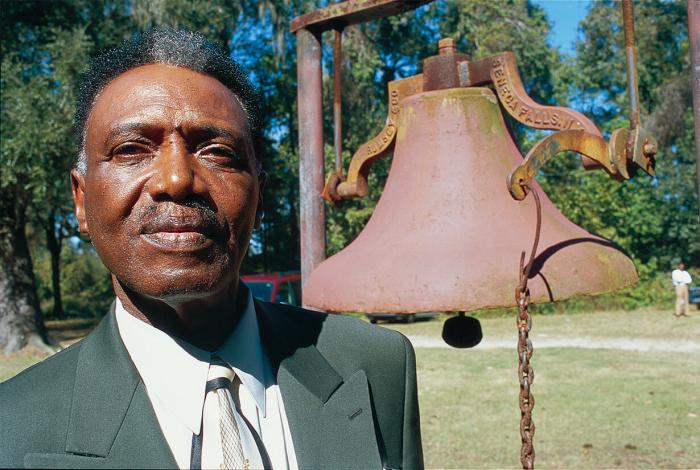

This quiet coastal preserve, with its mossy shade oaks, sand streets and hospitable residents, is the epicenter of the Gullah Nation.

Scholars call it one of the South's last contiguous, fully preserved communities of Gullah people, proud descendants of the agriculturally skilled slaves brought from rice-growing areas of western Africa, and the nation of Sierra Leone in particular, as early as the 1500s. Forced into semi-isolation on their new continent's barrier islands, they developed a singular variant of African-American culture.

"It's not regular mainstream African-American culture," said Queen Quet, who describes herself as honorary chieftess of the Gullah Nation. "You can't say all black people in America have the same culture. You can't throw a cast net in the Hudson. It's not monolithic."

Quet, whose birth name is Marquetta L. Goodwine, sometimes serves informally as the voice, face and high-profile scholar of the multi-state Gullah community.

That community, called a "nation" by many members, encompasses the Sea Islands of coastal South Carolina and Georgia, taking in small adjoining swatches of North Carolina and Florida. The Gullah Nation extends 30 to 35 miles inland — up to 100 miles by some estimates — in each of those areas.

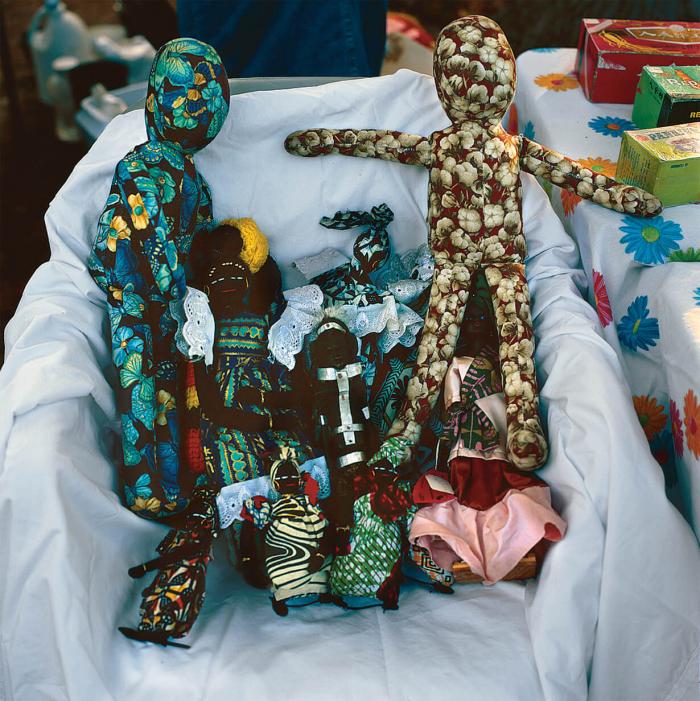

The Gullah — or Geechee, as they are usually known in Georgia — survive and often thrive in postmodern America. But they still cherish their traditional crafts (basketweaving, storytelling, cast net-making); their cuisine (rice, fresh seafood and homegrown vegetables); a values system that prizes education, self-sufficiency and environmental stewardship; and above all, their language, a curious African-English blend still spoken by as many as 750,000 people.

Yet, as with the Cajuns' French dialect in Louisiana or the Pennsylvania German of the Amish, the language may be the most vulnerable part of Gullah culture. Some St. Helena educators complain that students in the Beaufort County School System, which includes the island, encounter teacher disapproval in the classroom when they converse in the Gullah they have learned from parents or grandparents.

"Sometimes that child is chastised for speaking 'broken English,' but it's not the child's fault; it's the teacher's lack of knowledge," said Walter R. Mack, who directs youth development programs at historic Penn Center, started by Philadelphia Quakers as a school for freed slaves in 1862 and today functioning as a museum-education complex charged with preserving Gullah/Geechee culture. "We tell our kids that they're bilingual."

The linguistic-cultural clash, Mack suggested, arises when public school teachers from other parts of the country lack understanding of their new students' backgrounds. "They have little knowledge of, or respect for, Gullah culture," Mack said.

"He's absolutely right," said Cynthia Gregory-Smalls, assistant principal at St. Helena Elementary School. "We have people coming from areas where they have not seen African Americans except on television."

In response, Penn Center has pushed for greater cultural orientation of newcomer teachers, Mack said. Meanwhile, the PACE program seeks to set an example of cultural sensitivity toward students aged 3 to 17 in its daycare, after-school and summer enrichment programs, and its Teen Leadership Institute. High school graduation rates are very high for students in PACE programs, Mack said, reaching 100% for students who spend four years in PACE.

"Through the years, they've become proud of who they are," Mack said. "It's always been our philosophy that, to instill self-esteem in children, it's important for them to know their own culture."

St. Helena Elementary stands just a few blocks to the east on Sea Island Parkway/Highway 21, the island's main road.

"We spend lots of time at the Penn Center," Gregory-Smalls said.

The school has a number of students enrolled in PACE and has a convenient field trip destination in the Center's York W. Bailey Museum, named for an island native who became its first black physician. The museum features cooking implements, clothing irons, crockery and blacksmithing tools, as well as a photographic gallery of Penn Center students dating back to the 1800s.

The museum also offers a regular weekday array of "cultural lessons" geared to grades K-12, with topics including the patchwork quilt, a key Lowcountry tradition; Griot (pronounced GREE-oh), an African and African-American tradition of storytelling in song; Sea Island sweet grass baskets, originated in West Africa and still handmade and sold by the score in coastal South Carolina; and "Casting the Net," featuring a master net-maker creating a net and, weather permitting, using it to haul up a meal of shrimp from local waters.

'Renaissance' of a culture

At St. Helena two years ago, Queen Quet helped found the International University of the Gullah/Geechee Nation, headquartered in a restored home just across Highway 21 from Penn Center. The university's inaugural semester last summer offered Gullah-oriented courses in psychology, history, religious studies and even computer science.

A nearby nonprofit, the South Carolina Coastal Community Development Corporation, fosters the Gullah values of self-sufficiency by helping what it calls "low-wealth" people start business ventures, such as packaging ready-to-eat Lowcountry dishes in the corporation's commercial-scale kitchen.

Growing validation by the majority culture — even the National Park Service has studied ways to preserve Gullah/Geechee culture — leaves many scholars optimistic about its long-term survival.

The Rev. Elric Sampson, a Franciscan priest from Chicago who studied Gullah culture as part of a yearlong sabbatical in Savannah, worries that some cultural hallmarks, such as basketweaving, might not survive among Sea Island youth. But survival of the overall culture, he says, now seems certain: "As a country, we're coming to value diversity more."

Someday soon, the future of Gullah/Geechee culture — and the political acumen needed to defend it — will fall to the kids who are now learning about it in schools like Penn Center.

"There are many aspects of it that are being kept alive, especially as a result of a renaissance in the last few years," said Alada Shinault-Small of the College of Charleston's Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture. "When I was growing up, the Gullah/Geechee culture was kind of swept under the rug and very much misunderstood and misrepresented. It's a buzzword now."

That buzzword is being passed along to the next generation.

"They are the ones with the task of keeping it going," Shinault-Small said. "That's the key component of preservation."

Like those school children rehearsing Whittier's song of freedom and perseverance:

Come once again, O blessed Lord!

Come walking on the sea!

And let the mainlands hear the word

That sets the Island free!