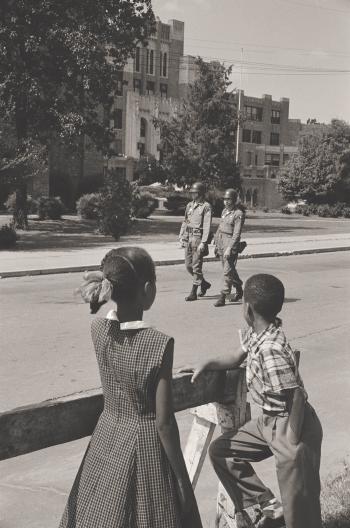

On September 4, 1957, Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus ordered National Guard troops to surround Central High School in Little Rock, to keep nine black teenagers from entering. His action was in direct defiance of the Supreme Court's 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which said black students had a right to attend integrated schools. That same afternoon, a federal judge ordered Faubus to let the black students attend the white school.

The next day, when 15-year-old Elizabeth Eckford set out for class, she was mobbed, spit upon and cursed by angry Whites. When she finally made her way to the front steps of Central High, National Guard soldiers turned her away. An outraged federal judge again ordered the governor to let the children go to school.

Faubus removed the troops but gave the black children no protection. They made it to their first class but had to be sent home when a violent white mob gathered outside the building.

President Eisenhower, saying "our personal opinions have no bearing on the matter of enforcement," finally federalized the National Guard, and, for the rest of the school year, soldiers walked alongside the Little Rock Nine as they went from class to class.

The next year, Gov. Faubus shut down all the public schools rather than integrate them. A year later, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that "evasive schemes" could not be used to avoid integration, and Little Rock's schools finally opened to black and white students alike.

Fifty years later, the country continues to grapple with racial segregation in its schools. In Little Rock, a park ranger, a civics teacher and a team of 15-year-olds armed with tape recorders are revisiting the lessons of the past to help change the future.

Spanning two city blocks in a modest neighborhood south of downtown, Central High School in Little Rock, Ark., looks in 2007 almost exactly as it did 50 years ago.

In September 1957, nine brave Black students crossed a line of armed soldiers to integrate Central High, in the first major test of school desegregation after Brown toppled the notion of "separate but equal."

At its peak, the building rises five stories, an ornate pinnacle flanked on either side by three-story, tan-brick wings. Four stone statues stand watch above the front doors. Twin staircases spiral down from the entrance, spreading into a maze of sidewalks crisscrossing a wide, green lawn. In the middle of the lawn is a reflecting pool.

Though this is still an operating high school, on most days tourists stop here. They wander the grounds in clusters, pausing to stand next to the reflecting pool, pointing their cameras upward. They shield their eyes from the sun, squinting to read a sign bearing the school's name. They lean down to remind their children what happened here.

This September, Little Rock will honor the 50th anniversary of the Little Rock Nine. The anniversary is more than a chance to look back and honor ordinary students who turned into heroes. It also is a chance to look forward, to see exactly how far we still must travel to achieve the promises set out in Brown.

'Neglect of history'

The 1957-58 school year at Central High left deep wounds, the kind that heal slowly. Some white residents in Little Rock report feeling vilified by the events of that year, while other residents -- black and white alike -- say the city still has a long way to go.

"When you think about what happened, there's a little bit of -- not embarrassment, that's not the word – but a discomfort in how to talk about it," says Laura Beth Arnold, an administrator with the Little Rock Independent School District. "We have an anxiety around it: 'If I dive into this, the class is going to have a discussion about race, and I'm not sure how to deal with that.'"

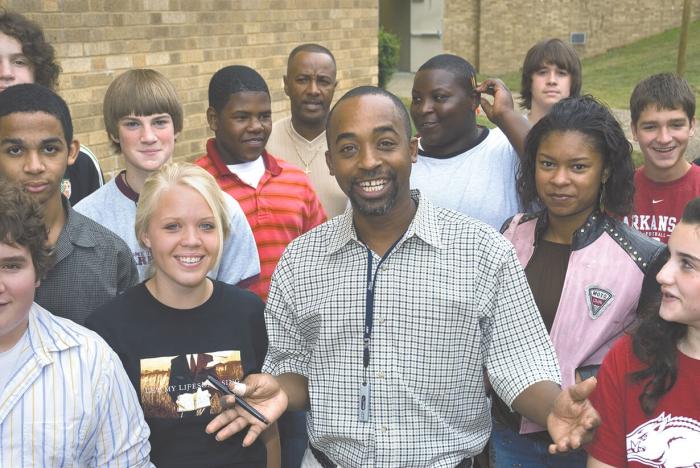

The event that drew international media coverage and pitted governor against president gets a paragraph in the school's civics textbook and is barely mentioned in some history books. As a result, many students and some teachers at Central didn't fully understand the story of the Little Rock Nine. Central High civics teacher George West calls this "a neglect of history."

"The doors of Central became the gates of change for an entire America," West says. "Yet so many students at Central knew virtually nothing about the events that happened here."

West has taught history and civics for more than 20 years, four of them at Central. He grew up in Little Rock; his father-in-law was the chairperson of the STOP committee, a grassroots movement in the late 1950s to support integration. As a trained oral historian, West was disturbed by his students' lack of knowledge.

Then, in 2005, Laura Miller from the Central High School National Historical Site picked up the phone and called West with a request: Could he help design a curriculum about the Little Rock Nine that would interest teachers across the country? Quickly, West said yes.

'Not just about Little Rock'

Across the street from Central High School stands an old Mobil gas station. Outside, the building has been restored to its 1950s-era condition. Inside, U.S. park rangers answer questions as visitors roam through a maze of timelines, photographs and video monitors. This is the Central High School National Historical Site. Opened as a nonprofit museum in 1997 in conjunction with the Little Rock Nine 40th anniversary, the National Park Service assumed ownership in 1998. The visitors' center here welcomes more than 45,000 people each year and is the only museum in the country exclusively dedicated to this piece of civil rights history.

"This isn't just a story about African Americans. It's not just a story about Little Rock. It isn't a story of good vs. evil," says Miller, the historical site's interpretive director. "It's about how we, as Americans, have the responsibility to make things better and more equitable for everyone."

To coincide with the city's 50th anniversary celebration this September, the Park Service is building a larger visitors' center next door, which will house exhibits about other human rights struggles – from immigrant rights, to disability rights, to gay rights – making the connection between what happened at Central High School and other, contemporary struggles for human rights.

"Today, to read the newspaper, it's almost like reading the papers from 1957," Miller says. "The language that's used to talk about immigrants, or gays and lesbians – it's the same language that was used to talk about African Americans in the 1950s."

Moving backward

On a more basic level, what makes the story of the Little Rock Nine still relevant are the invisible lines, dividing schools and neighborhoods, that continue to separate Americans by race and class.

The chance that a Southern black student will attend a majority-white school is 32,000 times higher today than it was in 1954, according to Harvard's Civil Rights Project. Yet, a recent study released by the Project reveals a deeply troubling trend: Public schools today are more segregated along race and class lines than at any point in the past 30 years.

The 2003 report found that only 14 percent of white students ever attend multiracial schools. In 44 percent of U.S. public high schools, the student population is almost entirely black. Researchers call this trend "resegregation."

For example, in Little Rock, white residents comprised a majority of the population in the 2000 census, yet white youth accounted for only 29 percent of the public school enrollment. Some see this as a remnant of the late 1950s, when a sudden growth of private schools appeased white families uncomfortable with integration.

"Most of the progress of the previous two decades in increasing integration in the [South] was lost," writes Gary Orfield, the Harvard study's co-author, in Rethinking Schools. "The South is still much more integrated than it was before the civil rights revolution, but it is moving backward at an accelerated rate."

A primary reason is a string of Supreme Court decisions in the early 1990s that relaxed the standards by which school integration was defined. Nationally, school integration reached its peak in the late 1980s; ever since, it's declined.

The costs of resegregation are high. Segregated minority schools are disproportionately poor, with larger class sizes, fewer advanced courses and lower college enrollment rates for graduates than their segregated white counterparts.

Several studies have shown that integrated schools bolster test scores and college enrollment and improve intergroup relations among students of different racial backgrounds. However, when school districts attempt to address issues of racial equity, they often meet with controversy.

- In April 2006, the Nebraska state legislature approved a measure to split the Omaha school system into three separate districts, loosely divided along racial lines – one for white students, one for black students, one for Latinos. Supporters argued it would give minorities greater control over their own schools. Opponents labeled it segregation.

- In June 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear two appeals from white parents in Seattle, Wash., and Jefferson County, Ky., who argued their school districts discriminate against white students by using race as a factor when assigning students to schools.

- In July 2006, the Supreme Court let stand an earlier decision, made prior to the retirement of Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, rejecting the challenge to a policy in Lynn, Mass. The Lynn school district considers race when approving school transfers. The lawsuit by parents was the first challenge to a voluntary desegregation plan to make it to trial.

Legal scholars claim more than 1,000 race-based school assignment policies are in place in districts across the country. Opponents argue that these policies erroneously teach students that race still matters. Proponents argue that's exactly the point: Race does still matter, and policies leveling the educational playing field are sorely needed.

The Supreme Court, now with a new, conservative-leaning justice who didn't participate in the Lynn case, was scheduled to hear arguments in the Washington and Kentucky cases last fall. The decision, expected later this year, could have sweeping repercussions for schools across the nation.

'Part of a huge story'

Crowded around a bank of computers at the back of George West's classroom, three students spent much of their spare time last summer building a Web site that would house the Central High School Memory Project.

The curriculum West and his students designed addresses the roots of democracy and how people throughout history have been excluded from its benefits. Students talk about what it means to act heroically, what it takes to change society. They learn how to map social justice movements. To make the project interdisciplinary, West partners with an English teacher, who leads students in a discussion of Warriors Don't Cry, a memoir by Little Rock Nine member Melba Pattillo Beals.

And then, students get out the tape recorders.

After learning interviewing skills -- listening for changes in tone of voice, paying attention to body language, recording details about the physical surroundings -- students set out to interview older relatives about their memories of the Civil Rights Movement. Students transcribe the interviews and then turn them into essays.

Verdia Abrams, a senior, interviewed her father, who grew up in an African-American neighborhood near Central High.

"When he was 10 or 11, he was a paper boy," Verdia says. "A couple of days after Martin Luther King was assassinated, Little Rock was under curfew. He had to break the curfew to deliver his papers. A truck of guardsmen stopped him and pointed their guns at him and asked where he was going. They used the 'n' word. They said, 'If you run, we're going to shoot you.' Finally, they let him go, and he ran home.

"I was like, 'Oh my gosh!' I never imagined he actually had to go through those things. I wasn't born during that time, so I didn't think it affected me. But knowing that things like that happened to my dad and people I love really brings it home."

One student learned his grandfather had been a New York Times reporter on assignment in Selma, Ala., during the march to Montgomery. Another learned her mother had been "scrubbed down" by her parents after dancing with a black student at a high

school dance. Another interviewed a white man who had been in the angry crowd of segregationists protesting Central High's integration.

West had hoped the act of interviewing and then writing about history would help make the Civil Rights Movement come alive for his students. He thought it would help students feel connected to their own pasts and gain a better understanding of how individuals can contribute to large-scale, social justice movements. But he didn't expect the essays to be of value to anyone but the students.

"I was wrong," he says. "What's significant is that you're getting the attitudes and perspectives of a 15-year-old today about what's significant in this 65-year-old's memory. This suggests how ideas, values and a sense of struggle are passed on."

So the students and West decided to create a Web site. By the summer of 2006, they had collected 250 essays. By the 50th anniversary, every essay will be archived online, indexed by topic and time period.

"I'm intent on having other teachers in other towns adapt this to other events in history that shaped their communities – when the railroad came, when the steel mill left," West says. "There are things in history that changed the way people lived... The more we know about them, the better we understand our history and the better off we are."

The project has helped students and teachers at Central learn how to start talking about race.

"There were lynchings in families," says Mike Johnson, another civics teacher at Central whose students participated in the Memory Project. "Tears were shed. It's eye-opening to hear these stories."

Adds senior Tafi Mukunyadzi: "You realize you're not just a person walking through this earth on your own. You're part of a huge story. We all had family members who had a story about the Civil Rights Movement. So we're all connected through that."

'That's me'

Across the street at the Historical Site, two dozen middle school students in matching purple shirts wander through the exhibits. They stand in clumps, captivated by the photographs, leaning in to read the timeline painted on the wall.

They're here on a day trip from a summer camp in Emoba, Ark., one of three groups on today's schedule. Every child in the group is African American; the group before them was mostly white.

As the group nears the end of the tour, a woman enters the room. Her name is Carlotta Walls-Lanier, and she's dropping by the visitor's center during her trip this week to Little Rock.

Tall and elegant, Walls-Lanier weaves through the crowd of students and peppers them with questions: "Are you having a good time?" "Does anyone have any questions?" At first, the students seem surprised: Who is this stranger, and why is she speaking to us? Then Walls-Lanier points to a photograph on the wall.

"That's me," she says.

One student asks, surprised, "Are you one of the Little Rock Nine?"

"That's right," she says, nodding her head.

She then points to another picture, of the Nine sitting on the steps of the Supreme Court building, with Thurgood Marshall sandwiched in the middle. She tells them what it was like to watch Marshall argue their case in court. "He," she tells the students, scanning the room, "was my hero."

Walls-Lanier asks the group if anyone has any questions. At first, no one responds. Finally, after several seconds, a student raises her hand.

"How was your first-day experience?" she says.

Quickly, the questions begin to flow, the students' voices layering on top of each other, asking questions so quickly that Walls-Lanier doesn't have time to respond.

"What was going through your mind that day?"

"Did you talk with each other every day about what had happened to you?"

"Did someone teach you how to deal with the mobs?"

"Hold on, hold on," Walls-Lanier says, holding her hands up, laughing.

The students quiet. And she begins to tell the story.