My name is Helen Tsuchiya. My maiden name was Tanigawa. Growing up, my family included my parents, three sisters and one brother. My parents were born in Japan but I was born in the United States. My father was a farmer, growing grapes on our family farm.

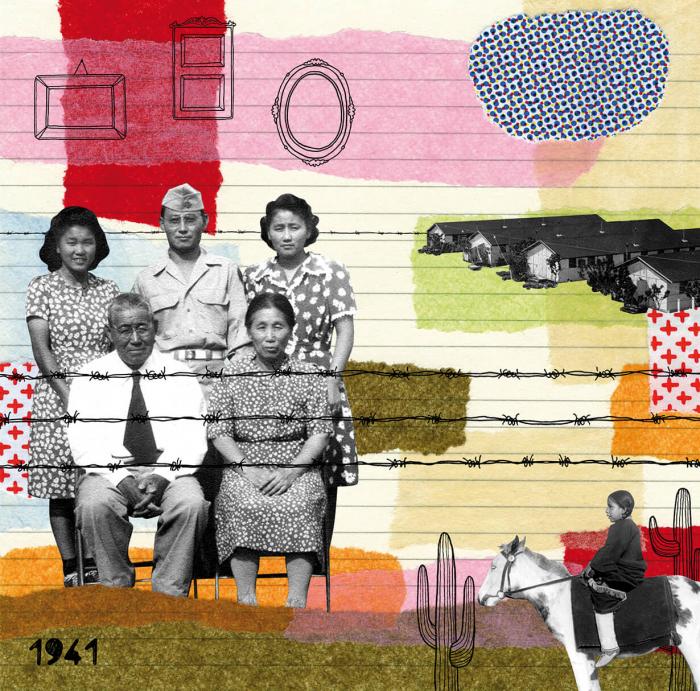

Many things changed for me on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States declared war on Japan. Many believed that Japanese Americans could not be trusted. Executive Order 9066 was passed, which said that Japanese Americans must be put in internment camps. This is difficult to understand because everyone in my family was a U.S. citizen.

Japanese Americans were evacuated from their homes. We had only a few weeks to prepare and we could take only a few things with us. We sold some of what we owned for very little money. My mother left family pictures and wedding photographs on the wall. She said they that they would protect our home when we are gone. She really believed we would all return to our home in California. But in one day everything was stolen — even the pictures. It broke my mother’s heart.

The internment camp was surrounded by barbed wire. For three years we lived in a 20-by-20-foot room in barracks. We had no privacy, and it was so dusty it was difficult to breathe.

A Pima girl who lived nearby would come up to the fence and talk to us. She felt sorry for us confined in the camp, while we felt sorry for her, confined to the reservation.

Fifty years later I revisited the camp and met that Pima girl. She said, “My Grandfather would take me to the camp on a pony. I remember the children reaching across the barbed wire to feel the pony. Even though I was 3 years old, that experience stayed with me.” Now she’s serving her people as a nurse on the reservation.

The survivors later received $20,000 as an apology from the government. But my parents had already died — they were the ones who really deserved the apology. Before the war they owned 40 acres of farmland but lost it all because they could not make the payments while in the internment camp.

During the war my brother joined the Army to prove his loyalty. He was sent to Fort Snelling in Minnesota to learn Japanese so he could fight alongside U.S. forces in Japan. After the war he found work at an engineering company. His boss loved him like his own child. We moved to Minnesota to join him.

When you think about it, it’s my parents who really suffered. Now I want to share my story with the children so it will never happen again.

Helen Tsuchiya told this story to folklorist and folksinger Larry Long. Long is the creator of Elder’s Wisdom, Children’s Song, a project that brings elders into the classroom to share their stories with children, who retell the stories in song. For more information, go to www.communitycelebration.org. To learn more about Americans of Japanese ancestry who fought for the U.S. in World War II, go to www.goforbroke.org.