“After all there are no innocent bystanders. What are they doing here in the first place?”

—William S. Burroughs

A 14-year-old hangs herself. a 19-year-old jumps off a bridge. A 13-year-old shoots himself. Another loads his backpack with stones and leaps into a river. Still another swallows her father’s prescription meds to get rid of the pain and humiliation. A 17-year-old is found hanging outside her bedroom window. Two more 11-year-old boys kill themselves within 10 days of each other.

These young people all had two things in common: They were all bullied relentlessly, and they all reached a point of utter hopelessness. Bullying is seldom the only factor in a teenager’s suicide. Often, mental illness and family stresses are involved. But bullying does plainly play a role in many cases. These students feel that they have no way out of the pain heaped on them by their tormentors—no one to turn to, no way to tell others. So they turn the violence inward with a tragic and final exit.

Most of the bullying that helped cause these tragedies went on without substantial objections, indignation, intervention or outrage. The bullies were far too often excused, even celebrated. The bullied were usually mourned after their deaths. But at times they were also vilified in order to justify the bullies’ actions. We are devastated by the final act of violence but rarely outraged by the events that lead up to it.

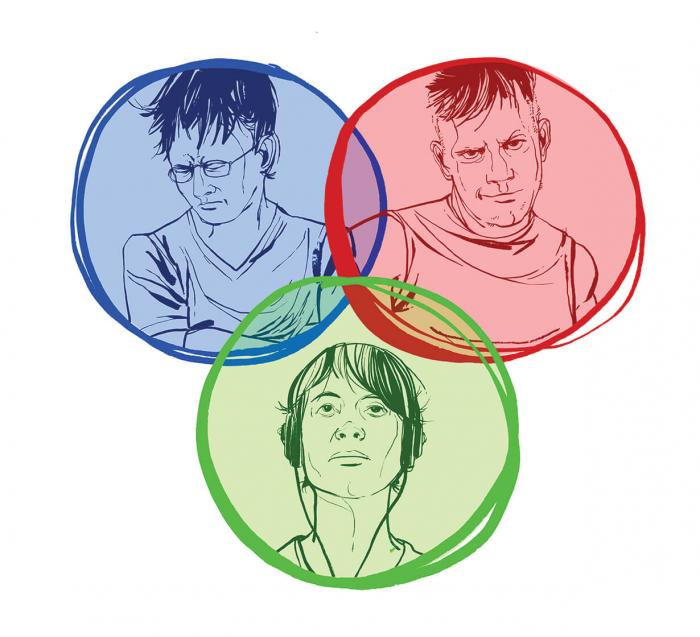

An Act With Three Characters

There are not just two, but three characters in this tragedy: the bully, the bullied and the bystander. There can be no bullying without bullies. But they cannot pull off their cruel deeds without the complicity of bystanders. These not-so-innocent bystanders are the supporting cast who aid and abet the bully through acts of omission and commission. They might stand idly by or look away. They might actively encourage the bully or join in and become one of a bunch of bullies. They might also be afraid to step in for fear of making things worse for the target—or of being the next target themselves.

Whatever the choice, there is a price to pay.

Actively engaging with bullies or cheering them on causes even more distress to the peer being bullied. It also encourages the antisocial behavior of the bully. Over time, it puts the bystanders at risk of becoming desensitized to cruelty or becoming full-fledged bullies themselves. If bystanders see the bully as a popular, strong, daring role model, they are more likely to imitate the bully. And, of course, many preteens and teens use verbal, physical or relational denigration of a targeted kid to elevate their own status.

Students can have legitimate reasons for not taking a stand against a bully. Many are justifiably afraid of retribution. Others sincerely don’t know what to do to be helpful. But most excuses for inaction are transparently weak. “The bully is my friend.” “It’s not my problem!” “She’s not my friend.” “He’s a loser.” “He deserved to be bullied—asked for it.” “It will toughen him up.” “I don’t want to be a snitch.” Many bystanders find it’s simply better to be a member of the in-group than to be the outcast. They’re not interested in weighing the pros and cons of remaining faithful to the group versus standing up for the targeted kid.

But injustice overlooked or ignored becomes a contagion. These bystanders’ self-confidence and self-respect are eroded as they wrestle with their fears about getting involved. They realize that to do nothing is to abdicate moral responsibility to the peer who is the target. All too often these fears and lack of action turn into apathy—a potent friend of contempt (see resources).

The Rewards of Bullying

Bullying often appears to come with no negative consequences for the culprits. Indeed, it can provide a bounty of prizes, such as elevated status, applause, laughter and approval. The rewards contribute to the breakdown of the bystanders’ inner objections to such antisocial activities. As a result, you soon see a group of peers caught up in the drama. Once that happens, individual responsibility decreases. The bully no longer acts alone. The bully and the bystanders become a deadly combination committed to denigrating the target further.

This “trap of comradeship” reduces the guilt felt by the individual bystanders and magnifies the supposed negative attributes of the target. “He’s such a crybaby. He whines when we just look at him.” “She’s such a dork. She wears such stupid clothes and walks around with her head hung down.” The situation becomes worse when the victim’s supposed friends stand idly by—or, worse, join in with the bullies. The hopelessness and desperation of the target is compounded by the realization that these “friends” abandoned him.

All this leads to more serious problems. The lack of sanctions, the breakdown of inner objections, the lack of guilt and the magnification of a target’s weakness all contribute to the cultivation of a distorted worldview. This worldview reinforces stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination. That, in turn, hinders kids from developing empathy and compassion—two essentials for successful peer relationships.

The Fourth Character

Another potential actor can bring the curtain down on this tragedy. This fourth character—the antithesis of the bully—gives us hope that we can break out of the trap of comradeship. This character can appear in three different and vital roles—those of resister, defender and witness. He or she actively resists the tactics of the bullies, stands up to them and speaks out against their tyranny. The fourth character might also defend and speak up for those who are targeted. Bullying can be interrupted when even one person has such moral strength and courage. This fourth character is a reminder that choices are possible, even in the midst of the culture of meanness created by bullying. Here are some examples:

- When the high-status bully in eighth grade told all the other girls not to eat with a new girl, Jennifer not only sat with the new girl, but took in stride the taunts and threats of the bully and her henchmen: “Miss Goody-Two-Shoes, you’re next!”

- When a group of teens mocked a student because of his perceived sexual orientation, Andrew refused to join in and shrugged off the allegations: “What, are you chicken?” and “You’re just like him.”

- When a group of 7-year-olds circled Derek, taunting him with racial slurs, another 7-year-old, Scott, told them “That’s mean.” He turned to Derek and said, “You don’t need this—come play with me.” The bullies then targeted Scott. Derek told him he didn’t need to play with him if the others were going to target him, too. Scott’s response: “That’s their problem, not mine.”

- When 15-year-old Patricia was tormented by her peers at a small-town high school, one senior named Brittne stood up for her. But Brittne’s courage cost her dearly. She was cyberbullied, verbally attacked at school and nearly run over on Main Street. For the girls’ own safety, they were moved to another school in an adjacent town. Brittne had been in line to be valedictorian. Moving meant she had to give that up, costing her several scholarships. Yet Brittne says, “I would defend her again.”

Fifty Pink Shirts

Bullying can be challenged even more dramatically when the majority stands up against the cruel acts of the minority. For instance, seniors David and Travis watched as a fellow student was taunted for wearing a pink polo shirt. The two boys bought 50 pink shirts and invited classmates to wear them the next day in solidarity with the boy who was targeted.

Most bullying flies under the radar of adults. That means kids can be a potent force for showing up bullies. But speaking out can be complicated, risky and painful. Even telling an adult can be a courageous act. As parents and educators we must make it safe for kids to become active witnesses who recognize bullying, respond effectively and report what takes place.

Establishing new norms, enforcing playground rules and increasing supervision are policy decisions that can help reduce the incidents of bullying. So can having a strong anti-bullying policy. It must include procedures for dealing effectively with the bully, for supporting and emboldening the bullied and for holding bystanders to account for the roles they played.

Merely attaching an anti-bullying policy to the crowded corners of our curriculum is not enough. With care and commitment, together with our youth, we must rewrite this script—create new roles, change the plot, reset the stage and scrap the tragic endings. We can’t merely banish the bully and mourn the bullied child. It is the roles that must be abandoned, not our children.

We can hold bullies accountable and re-channel their behaviors into positive leadership activities. We can acknowledge the nonaggressive behaviors of the kid who is bullied as strengths to be developed and honored. And we can transform the role of bystander into that of witness—someone willing to stand up, speak out and act against injustice.

Bullying takes place because some people feel a sense of entitlement, a liberty to exclude and intolerance for differences. We can use the stuff of everyday life to create a different climate in our schools. This new climate must include a deep caring and sharing that is devoted to breaking the current cycle of violence and exclusion. It’s a daunting task but a necessary one.