In September 2011, Paul Phillips stepped out of his football team’s field house and into a struggle over the separation of church and state. Like most teams, Paul’s practiced after school. But one day he found that the coach had called in a local minister to conduct a weekly half-hour “team chapel” before practice.

“[The minister] would come in and tell some story that at the end would relate to a biblical story or something about God,” says 16-year-old Paul (which is not his real name). “The coach would stand off to the side while he [the minister] talked. And then the minister would finish and we’d get up and go practice.”

Paul, who does not believe in God, knew that the law would be on his side if he complained. The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that public schools may not endorse prayers or religious activities.

Team chapel would surely fit in this category, but Paul worried about what his coach, a deeply committed Christian, might do if he found out about Paul’s beliefs. Paul knew that most of his teammates had no problem with the coach inviting a minister to talk about God at school; some would even be angry at anyone who tried to stop it. “At least 95 percent of them are religious,” he says.

Religious minorities in public schools face situations like Paul’s every day, and student athletes face them more often than most. Why? In part because the conservative culture of many athletic programs is slow to accept legal changes—or the increasing religious diversity of the United States. Also, some coaches may feel that religion is a good—if not the only—way to bring out the best qualities in young athletes.

“I think it’s fair to say that it’s more difficult to convince some of the coaches,” says Charles C. Haynes, director of the Religious Freedom Education Project at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. “It’s tough to move from ‘we’re all good Christian people here’ to ‘we have to protect the rights of conscience for everybody.’”

Remaining Neutral

In the 1960s, the U.S. Supreme Court protected the right of conscience by issuing a series of landmark cases on religion in schools, starting with Engel v. Vitale in 1962. Among other things, the high court prohibited schools from leading prayers or school-sponsored Bible readings, and from giving clergy preference in speaking to students. Essentially, the court required public schools to remain neutral on all religious matters.

Some people misunderstood the intent of these Supreme Court decisions, but in reality, the rulings did nothing to interfere with the personal religious observances of young people. Students remained free to pray alone or in groups, as long as they didn’t disrupt school or interfere with the rights of others. In fact, under current law, students may pray during their free time, wear religious symbols, take the Bible or other holy books to school, talk about their faith with classmates and, in secondary schools, form religious groups if the school allows other extracurricular clubs.

However, many conservative Christians saw the 1960s-era decisions by the Supreme Court as an attack on their faith. “Eighty percent of the American people want Bible readings and prayer in the schools,” said the Rev. Billy Graham in 1962. “Why should the majority be so severely penalized by the protests of a handful?”

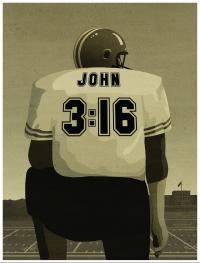

That view has been reinforced by such groups as the Fellowship of Christian Athletes (FCA) and Athletes in Action, both of which formed thousands of coach-led clubs—or “huddles,” as the FCA calls them—in public schools. In 2009, the FCA was the largest sports ministry in the world; it now reaches 2 million students. Some professional athletes—including New York Jets quarterback Tim Tebow, whose signature celebration pose of kneeling on one knee in prayer became known as “Tebowing”—also contribute to an increasingly religious atmosphere in sports.

Defying the Courts

Given the growing inclusion of religion in sports, it’s not surprising that several recent high-profile legal cases involving religion in schools were related to athletics.

In the 2000 Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe case, two families—one Mormon, one Catholic—filed suit against their Texas school district for allowing student-led, student-initiated prayer over the loudspeaker at football games. The high court ruled that the school’s policy was unconstitutional because loudspeaker prayers clearly were not private speech and effectively drowned out the voices of religious minorities. In 2009, the court also turned down an appeal from a New Jersey high school football coach who wanted to bow his head and kneel during prayers led by his players.

Legally speaking, U.S. public schools should be more religiously neutral than ever. Yet it is easy to find schools that routinely defy the Supreme Court’s rulings. Dawn Dupree Kelley is a principal in Birmingham, Ala., and the wife of a minister. She says that in her experience, just about any school-sponsored athletic event—from a football game to a volleyball banquet—can take on a religious flavor. “You don’t dare start off any venture without some sort of prayer,” she says.

Even when students question these traditions, determined schools find ways to skirt the Constitution. For instance, when Paul’s father complained to the principal about team chapel, the coach moved it off campus and declared it voluntary but continued to hold it at the same time each week.

Paul opted to skip the team chapel sessions. But, he says, there was still an underlying coercion to the situation. Because of his non-religious worldview, he was forced to skip the weekly school-sponsored religious event held during instructional time and attended by most of his other teammates.

After the school district received a letter from the Americans United for Separation of Church and State explaining why off-campus team chapel was still unconstitutional, district officials told the coach that he was to have no role in the weekly meetings and that they must be completely student run.

Despite the fact some coaches still see schools as places to promote their religious viewpoints, Haynes says, “there’s a trend to sort this out in public schools and get it right.” He has seen a growing awareness among educators of the laws concerning church-state separation and Supreme Court precedents. Also, a growing number of schools have adopted guidelines to help teachers deal with religious issues.

“In order to protect all the students, coaches have to be there for all the students,” Haynes says. “They cannot take sides in religion.”

More God Than Ever

Even today, a simple Google search can produce recent headlines from the mainstream media that say something like “Prayer Banned at Graduation” or “School Football Resumes After Prayer Ban.”

This is ironic for two reasons. First, prayer has never been banned in public schools—only school-sponsored prayer. Second, the Supreme Court decisions, aided by changes in federal law, have opened the door for students to become more religiously active at school, not less.

According to Charles C. Haynes, by the early 1980s, many schools had become religion-free zones. That is because cautious school officials overreacted to the controversies stirred up by the 1960s-era Supreme Court decisions. Wary of causing more controversy, they tried to keep out all mention of religion. It was not discussed in textbooks, and students were wrongly told to keep their religious beliefs at home.

Such incidents do still occur. In 2011, school officials at a Los Angeles elementary school tried to prevent a fifth-grader from singing the Christian song “We Shine” at its talent show. The principal mistakenly believed that allowing students to select songs with religious themes would violate the separation of church and state. However, when school officials allow students in a talent show to select which songs they wish to perform, they may not prohibit songs with religious content. After a threat of legal action, the school backed down and allowed the song.

Although these kinds of stories make a splash in the press, Haynes says that such incidents are much less common than they used to be. Increased litigation is one reason. Another is that a 1984 law called the Equal Access Act opened the door for student-initiated religious clubs in secondary schools.

“There are kids meeting around the flagpole [to pray] every September in thousands of schools,” says Haynes. “There are kids handing out religious tracts in thousands of schools across the country. There are kids praying in the lunchrooms. There are kids bringing scriptures [to school] and reading them at recess. Before the Equal Access Act of 1984, there was no such thing as a religious club in a public school. So this has been a sea change.”