“You are the hope of the future.” That’s the message Marian Wright Edelman, executive director of the Children’s Defense Fund (CDF), gave more than 1,500 excited college students and recent graduates as they began a week-long training for the CDF’s Freedom Schools. She was preparing them for a daunting task—that of transforming the educational prospects for thousands of students across the country.

Later, one group of trainees, crowded inside the confines of a bright Hula-Hoop, tried to move in tandem toward a pink and orange ball. In this exercise, the ball represents a child who struggles in class and fears that she, like her mother before her, will not finish school.

The trainees traded ideas about how to move closer and reach the “child” despite the encircling Hula-Hoop. In the follow-up discussion, team members expressed frustration about the barriers they had faced. Though the trainees had been afraid of failure, the exercise had forced them to speak up and build on each other’s ideas. More than anything, they had pulled together as a team.

This and other team-building activities—along with intensive study of reading instruction, language strategy, cultural economics, social justice, parent engagement and learning barriers—inform trainees’ work with real children in the CDF’s summer academic-enrichment program.

The trainees have become what Ella Baker—a civil rights activist who helped organize the original Mississippi Freedom Schools, coordinate the Freedom Rides and create the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the 1960s—referred to as servant leaders.

Modeled after the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools, which were designed to change a community by giving residents the tools to develop leaders and exercise their political power, modern Freedom Schools—such as those run by the CDF—emphasize the connection between education and freedom. Their main goal is to replace the cradle-to-prison pipeline with a cradle-to-college track.

Last summer, more than 11,300 students were served through CDF Freedom Schools sponsored by schools, churches and nonprofit organizations at 177 sites in 82 cities across the country.

“What we hope and have seen is that children will form a love of books and a love of ideas in books,” says Jeanne Middleton-Hairston, national director of the CDF Freedom Schools Program. “We want to empower children to understand that they are valuable … and not proscribed by their circumstances.”

Freedom Schools use techniques—such as call and response, motivational music and an emphasis on social action and family interaction—rooted in African culture, the black church and the civil rights movement. But CDF Freedom Schools are not an “Afrocentric program,” stresses Middleton-Hairston.

Instead, the racial makeup of each Freedom School reflects its community. At some, most students are children of mixed heritage. A growing number of students and servant leaders are Latino. In New Orleans, one Freedom School enrolled primarily Vietnamese students and embraced that culture. Teacher demographics are the reverse of most public schools. Nearly three-quarters of servant leaders are African-American, and more than one-third are men.

Regardless of demographics, all students benefit from cultural exchange and literature that features children and families of color.

The Original Freedom Schools

The legacy of the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools—that change comes from the bottom up—is timeless.

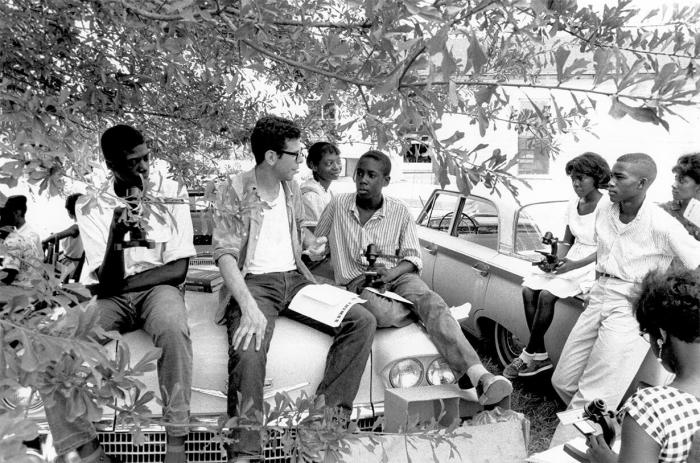

When the schools were founded, fewer than 6 percent of African Americans could vote, and schools for black children lacked basic resources. Inspired by the Highlander Folk Schools of the labor movement, groups like the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), SNCC and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) teamed up to create activists, organize residents, register voters and form an alternative political party that included African Americans.

Classes taught by student volunteers—including historian and college professor Howard Zinn and activist Stokely Carmichael—were held in churches, open fields and residential backyards and included a mix of black history, civil rights movement philosophy, leadership development, reading and math. Students ranged from preschoolers to adults.

The CDF Freedom Schools curriculum focuses on five content areas—academic enrichment; parent and family involvement; social action and civic engagement; intergenerational leadership; and nutrition and health.

Freedom School students read a selection of books they may not be exposed to during the school year, giving them the chance to connect on a deeper level with characters and circumstances that “work with the whole child and make a connection between what is read and what is in the minds of children,” said Dr. Carole McCollough, a retired library sciences professor who heads up the book-selection committee for CDF Freedom Schools.

Energetic cheers, chants and songs are also a big part of the CDF Freedom School culture. Students clap hands, tap feet and bob their heads to the beats of songs like the “Hallelujah Chorus” from Handel’s Messiah and the call-and-response chant “Rock the Freedom School.”

Fred Kelly, of Charlotte, N.C., saw a transformation in his son Iman after he attended a CDF Freedom School. Iman developed a new love of learning. “He started talking about reading things, which he never did before,” Kelly says. “He got to choose stories to read, and those stories were often connected to black history or the African-American experience. He felt like he could tell us new things at the dinner table.”

Iman, now 13, attributes his newfound love of reading to the CDF Freedom Schools’ curriculum. He says the books were about young people who excel in spite of adversity, and the lessons included activities. “I really like hands-on activities with the reading,” Iman said. “I know I need my education. I feel like I improved in reading, and I like participating in discussions now.”

Will Choice was 11 years old when he enrolled in a Freedom School in his hometown of Sanford, Fla. He says he struggled with reading and was frequently reprimanded for talking in class. He felt disconnected from traditional school. When he went to a Freedom School for the summer, his reading skills improved. His confidence soared.

Choice, now 20 and a junior at Stetson University, served as a servant-leader intern last summer at a Freedom School. “I feel like I owe where I am to Freedom Schools,” Choice said. “I hope to inspire at least one child to take interest in school.”

Many Freedom School graduates feel compelled to become servant leaders when they reach adulthood. They have firsthand knowledge of the power of the program and want to pay it forward.

This intergenerational model of education works. In 2010, a two-year study of CDF Freedom Schools in Charlotte, N.C., and Bennettsville, S.C., found that 65 percent of students’ reading test scores improved and 90 percent reported no summer learning loss. A study of Freedom Schools in Kansas found that students improved their reading skills by two grade levels.

Given these results, it’s not hard to agree with Wright Edelman’s sentiment—the CDF’s young servant leaders are indeed changing the future.

How to Build a Grassroots Movement

The most powerful component of the Montgomery Bus Boycott was the people who identified the injustice, devised a strategy to change it, and developed methods to communicate the plan and use alternative transportation. It’s a perfect example of the type of effective grassroots movement we saw recently as protesters in the Occupy movement sprang up across the country.

“The Occupy movement is the Montgomery Bus Boycott of our day,” says Kathy Emery, executive director of the San Francisco Freedom School. She says building an effective movement requires “planning, strategizing and thorough training in the discipline of nonviolent direct resistance.”

There is no one way to effect change. What’s needed is steady conversation exploring the issues needing change, says Emery. In addition to use of the arts and nonviolent resistance, the following steps help build a movement:

Think creatively about solutions to problems.

Build relationships one at a time.

Form networks and coalitions.

Study the civil rights movement.

Locate the civil rights veterans in your community and learn from them.

Take direct action.

The Way We Start the Day

This is the way (hey)

We start the day (hey)

We got the knowledge (hey)

To go to college (hey)

We won’t stop there (hey)

Go anywhere (hey)

We work and smile (hey)

’Cause that’s our style (hey)

We love each other (hey)

Help one another (hey)

There’s nothing to it (hey)

Just have to do it (hey)

This is the way (hey)

We start the day (hey)

‘Cause we don’t play (hey)

Now what you say (hey hey hey heeeey)

Other Modern Freedom Schools

The CDF Freedom Schools Program is only one of many based on the original Mississippi Freedom Schools.

In the summer of 2005, Kathy Emery helped launch the San Francisco Freedom School, a six-week Saturday adult course featuring civil rights history, presentations by civil rights movement veterans, discussions, film screenings, readings and activities.

Another program, the Chicago Freedom School, helps high school students create change in their communities. This year, 16 students will design projects to build healthy communities as well as fair and just schools.

In Detroit, after students walked out to protest failing schools, they called for a Freedom School. And in Arizona, a ban on ethnic-studies programs in public schools led students and teachers to organize the Paulo Freire Freedom School—a charter that focuses on social justice and environmental sustainability for middle school students in Tucson.

The 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools are a powerful model that warrants duplication nearly 50 years later, says Emery. “Schools are so essential to movement building,” she says. “The goal is to empower people.”