In a telling experiment conducted by Marilyn S. Rosenthal, children were asked to accept a box of crayons and drawing pad from one of two “magic boxes.” The boxes looked identical, but the voices that played from a hidden speaker within each box were different: Steve spoke Standard American English and Kenneth spoke African-American English. The interviewer played the same message from the different boxes, followed by questions such as “Which box has nicer presents?” and “Which box sounds nicer?”

The responses were revealing:

“I like him [points to Steve] cause he sounds nice. I don’t like him [pointing to Kenneth].”

“I think I want my present from Kenneth, if he doesn’t bite.”

“’Cause Steve is good, Kenneth

is bad.”

The children in the experiment ranged from ages 3 through 5. Children acquire attitudes about language differences early and these attitudes quickly become entrenched. Linguist Rosina Lippi-Green concludes in her book, English with an Accent: Language, Ideology, and Discrimination in the United States, “Accent discrimination can be found everywhere in our daily lives. In fact, such behavior is so commonly accepted, so widely perceived as appropriate, that it must be seen as the last back door to discrimination. And the door is still wide open.”

While other forms of inequality, prejudice and discrimination have become more widely recognized and exposed in recent decades, language prejudice is often overlooked and, in some cases, even promoted.

The Seeds of Language Prejudice

Children grow up in a world immersed in language attitudes. Adults use words such as “right,” “wrong,” “correct” and “incorrect” to label speech. Language that “falls short” of the sovereignty of Standard English is thrown into a single wastebasket, even when the phrases represent natural regional and socio-ethnic dialect traits. We are socialized into a simple dichotomy: Language forms are right or wrong.

Most people are shocked when they go to a different region and are told that they speak a dialect, since they take for granted that it is other people who speak dialects. But we all speak dialects, whether we recognize it or not. We may order a soda, pop, Coke, co-cola, tonic or soft drink to drink with our submarine sandwich, sub, hoagie, grinder, torpedo or hero, but we won’t eat unless we make a dialect choice in ordering our sandwich and carbonated drink. Dialects are inevitable and natural, and we all speak them.

Some ways of speaking have acquired regional, social and ethnic associations, becoming proxies for attitudes about particular regional and social groups. New York City regional speech is often viewed as aggressive and rude; Southern speech might be seen as backward and “country.”

Voices in television cartoons frequently portray villains as accented speakers of English. Standard English is reserved for superheroes and winsome characters. Even the voices in Disney’s animation reinforce stereotypes—main characters speak in Standard American or British dialects and mean or ignorant animals tend to speak in African-American English or Southern English.

It’s not surprising that young children develop prejudices about language differences that can accompany them through life—unless these stereotypes are challenged.

Commonsense Views and Dialect Reality

Most people think that dialects in the United States are dying out because of increasing mobility and the influence of a relatively homogenous media voice. But this is not the case.

Though there is some erosion of once-isolated dialects, some major dialect areas are actually diverging from each other. For example, a recent survey of the dialects in the United States reveals that the dialects of northern cities such as Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland and Buffalo are actually more distinct today than they were 50 years ago.

Studies of socio-ethnic language varieties such as African-American English and Hispanic English show that they are also more robust and distinct than they were in the past. Finally, new regional dialects are emerging in California, Oregon and Washington, as West Coast dialects develop a distinct regional voice that conveys, in part, a newly emerged social and regional identity.

Integrating Language Diversity into Education

Even as multicultural education moves forward, the study of language diversity has lagged behind. Educating students about language diversity should be an essential component of language arts, history and social studies—or better yet, all disciplines.

Several curricular programs on language and dialect differences have now been established and incorporated into public education programs with striking results.

A middle school curriculum developed in North Carolina includes a variety of activities ranging from analytical exercises to uncover the patterned nature of dialect differences to engagement with a rich array of audio and video resources featuring different local dialects. In one exercise, students examine what judgments they make about a person on the phone based on her accent or dialect.

Jeffrey Reaser’s study—developed in 2005 and updated in 2007—of student reactions to this language curriculum showed that there was a significant change in attitudes toward and knowledge about dialects. Ninety-eight percent of the students reported they learned something that would change the way they thought about dialects.

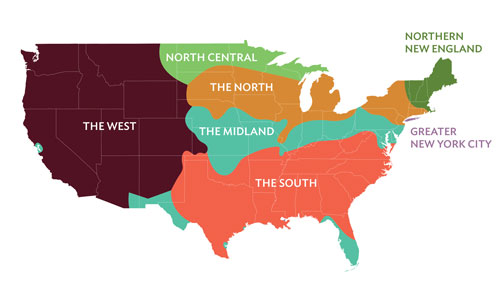

Based on dialect map by Rick Aschmann. For full map, including Alaska and Hawaii, visit aschmann.net/AmEng

Students noted that “dialects aren’t sloppy versions of Standard English” and that “they follow specific patterns that are logical.” They came to understand “there are tons of stereotypes, which are almost always wrong” and that “dialects represent people’s culture and past.” As one student put it, “[Dialects] are special and hold customs of how people live.”

Teachers also reported strong results. One said the examination of dialect differences “has proven to be empowering for my minority students. For many of them, this is the first time they have been told in a school setting that their dialect is valid and not ‘broken.’”

Teacher Leatha Fields-Carey reports that for both mainstream—and nonmainstream—speaking students “the recognition of language patterns and governing rules made the students feel for the first time that their varied use of ‘standard’ English did not indicate a lack of intelligence.” She observes that “to understand language is not only to know how to speak and write ‘Standard English’ correctly, but also to value the rich tapestry of language in all its forms.”

The study of language and dialect differences challenges a set of “common sense” assumptions, stereotypes and prejudices that too often fly under the radar, even in multicultural education. Unless we confront these attitudes, they will continue to negatively impact those who speak dialects other than Standard English—and that’s now a majority of the American population.

Three Things Teachers Can Do

1. Expose students regularly to language differences in cultural context.

Create opportunities for your students to connect with students from other dialect regions and groups via Skype to collaboratively explore language differences. Have them compare and discuss dialect words and pronunciations from their respective regions.

2. Challenge assumptions about language differences as they occur.

Students who negatively comment on the speech of others should be guided to examine the basis of their assumptions. For example, if a student says a particular pronunciation or word choice sounds “weird” or “funny,” initiate a conversation about the nature of language differences, how they develop and what they signify.

3. Integrate the discussion of language variation into the conversation of cultural and regional differences.

Language and dialect should be discussed as a natural consequence of other historical and culture differences. Include lessons examining how culture and history have influenced language variation when studying the history of Southern Appalachia, African Americans in the United States or American Indians.

Raise students awareness about the impact of language prejudice with our short video and activity.