Each year, thousands of North Carolina students study slavery as part of the North Carolina and U.S. history curriculum. It’s not an easy topic—in fact, many educators shy away from teaching about slavery beyond the bare minimum requirements. But in Buncombe County, North Carolina, the chance discovery of a cache of slave deeds led to an opportunity for students to move beyond textbooks and worksheets and connect with individuals who lived in their own community during slavery. It didn’t make the topic any easier, but it did lead to a community-wide collaboration that has connected Buncombe residents more deeply to their past and made them participants in history.

The Buncombe County Slave Deeds Project

Fostering agency is a central component of social justice education. But before students can see themselves as agents, they must see themselves as creators of history and connect with historical struggles—and peoples—of the past.

Deborah Miles, director of the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s Center for Diversity Education, knew that primary sources are an excellent vehicle for promoting historical empathy and agency. So in 1997, when local real estate attorney Marc Rudow told her he had stumbled on a collection of slave deeds while researching a parcel of land at the Buncombe County Register of Deeds, she was eager to use them with students. Slave deeds are bills of sale. Enslaved people were considered property, and any transfer of property was recorded between 1792 and 1865 when slavery was abolished. The cache Rudow found included more than 350 deeds.

With support from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, Miles organized a summer internship project for 10 high school and college students. The students worked long hours poring over the records, digitizing the documents and providing an initial analysis of each deed. Through this process they began to better understand both the human face of slavery and the dehumanizing practice of treating people as property, all while developing the skills of professional historians. “[They] became the diggers of history, not just passive recipients,” recalls Miles. “They made history and set in motion a chain of events that is still unfolding.”

It wasn’t long before Eric Grant, a curriculum specialist for the Buncombe County Schools district, took note of the project and extended its reach. Grant, working with students at a local alternative program for high school juniors and seniors, used an array of Google tools to magnify and manipulate the digitized deeds for transcription. Grant’s students begin to recognize names: Woodfin, Merrimon and Vance. These names mark the roads the kids travelled on their way to and from school every day—and they were the names of slaveholders. The connection flipped a light switch: Students began to realize how entwined the history of the region really was with their everyday lives.

Then, in 2012, Drew Reisinger, the newly elected Buncombe County register of deeds, learned of the students’ work and immediately saw the ethical and practical value of placing the deeds online. This act of transparency led Buncombe County to become the first in the country to make such deeds available to the public. These primary source documents could now be accessed not only by historians but also by family genealogists, who had once been locked out of the historical narrative of slavery in every former slave-holding county from Maine to Texas.

As word of this remarkable project spread, more community partners began to express interest. These partners now include state officials, professional and amateur genealogists, other local educators and nonprofit agencies. Faculty at a local university began using the online slave deeds with preservice teachers, many of whom plan to teach in Buncombe County. In one social studies methods course, students transcribed deeds, reviewed previously transcribed deeds, wrote lesson plans based on the documents and created 30-second public service announcement videos to broaden support for the project. The project was enthusiastically embraced. Preservice teachers gained a deeper understanding of the ways in which social justice education can work in the classroom, and, at the same time, became part of a larger community story about slavery, identity, reconciliation and the struggle to more accurately understand local history.

Teaching Transformation

Teaching the topic of slavery at any level can be both emotionally charged and confusing, so the educators behind the Buncombe County Slave Deeds Project took steps to prepare their students. While most of the high schoolers knew basic information about the institution of slavery, many had no real depth of knowledge about the experiences of enslaved people or slaveholders. Miles, Grant and other participants provided students with content knowledge and background information so that the deeds could be appropriately sourced and contextualized—a necessary step if students were going to formulate deeper research questions. Preservice teachers spent time discussing developmentally appropriate ways to address the topic of slavery in their future classrooms.

Working with the primary materials of the past has brought about countless transformative moments for the young people participating in the project. Ashland Thompson, a member of the original cohort of interns and now a Ph.D. candidate, reflects, “What was shocking to me was that so much documentation still existed in our community. I saw the relevance of tracing ancestry. I learned that summer, at a young age, that if I wanted to look at my past here is a way to do it—it can be done.”

“History has always been so distant from [students], both in time and space, but the deeds hit home for many of them,” Grant observes. “They also are confronted with some grotesque facts—the relative price of a young man versus a young female, the sale of an entire family, that some of the names are listed on wills alongside the exchange of furniture. Recognition of this is powerful and becomes personal.”

He recalls a time when one of the students, who had often struggled in school, looked up from a deed he’d been working on and marvelled, “I am holding someone’s life in my hands.”

Meeting Sarah Gudger

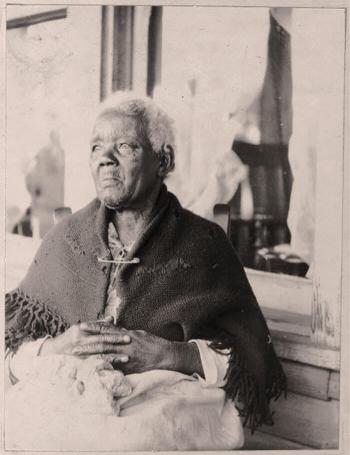

The power of the deeds project can be seen in the story of Sarah Gudger. She was born into slavery in 1816 near Old Fort, North Carolina, and lived to be 122 years old. One of the most compelling discoveries in the Buncombe County Register of Deeds office was the original deed documenting her ownership, allowing for new possible narratives and perspectives of her life. (More of her story can be found at the Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project.)

Drew Reisinger reflects, “Finding Sarah Gudger’s bill of sale was significant for me because I’ve seen Sarah’s picture (above), and I have read her interview in the Library of Congress Slave Narratives. It is her story that shows me what life was like in Buncombe County for a slave, and the connection between that story and the documents recorded in this office brought home to me the magnitude of history that sits on our shelves.”

Future Pathways

As word about the project has spread and educators have seen the value of students working firsthand with the Buncombe County slave deeds, other partners have come forward. Pam Smith with the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History contacted Reisinger and Miles and soon the project spread to Clemson University and the University of Georgia, evolving into a collaborative project entitled People Not Property. Historians, database experts and community advocates are now partnering to create a national slave deeds database using the investigative work of students throughout the country as they too become “diggers of history” in their own communities. In Buncombe County, the YMI Cultural Center will soon host a conference to provide an overview of the project and professional development for 50 teachers who want to use the deeds in their classrooms.

Says Smith, “We want teachers, students and family historians to be able to sit at their computers and access local county records for free—bills of sale, wills, inventories and more—some of the best historical documents available for connecting the dots and more easily finding the enslaved. This is cutting edge. It’s never been done before, and it’s time.”