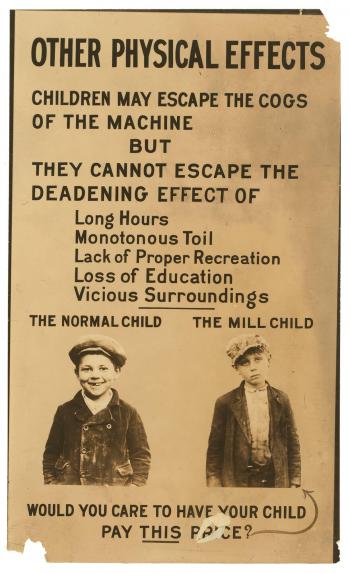

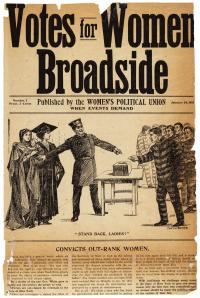

A black flag emblazoned with stark white letters that read, “A MAN WAS LYNCHED YESTERDAY.” A newspaper article written by a suffragist on hunger strike describing being force-fed by her jailers. Photographs of weary children on a poster underneath the title “Nearly Two Million Child Workers Under Sixteen Years To-day.”

All of these objects are powerful records of some of the country’s great social justice movements. They are primary sources, the raw materials of history.

Primary sources are documents or objects that were created during the time under study, often by participants in or eyewitnesses to historic events. These windows into the past are excellent teaching tools for engaging students with complex subjects, while also supporting the development of higher-order thinking skills.

By preserving evidence of the actions, voices and daily lives of social justice advocates and everyday people, primary sources represent history at its most personal. Engaging with these unique artifacts in an informed and critical way empowers students not only to grapple with the richness and complexity of history, but also to bring the voices of the past to bear on the issues of today.

Discovering Primary Sources

One of the world’s richest sources of primary source documents is available at students’ and teachers’ fingertips: the website of the Library of Congress, loc.gov. The Library’s online collections span centuries of human history and include millions of items in a wide variety of formats: handwritten letters, sheet music, photographs, oral histories, maps, films and more.

Rebecca Newland, the Library of Congress 2013-14 teacher in residence, has placed primary sources at the core of her instruction in multiple settings, from the English classroom to her middle school library. “Engaging students with primary sources immerses them in historical study in a way that nothing else but a time machine could achieve,” Newland says.

The “time machine” offered by primary sources invites students to ask questions that beg answers—and motivates them to seek those answers. In this mode of inquiry, many students will:

Engage with content.

Examining materials from the past personalizes history, establishing a connection that allows students to navigate distant or challenging subject matter.

Develop critical thinking skills.

By analyzing primary sources, students move from making concrete observations to questioning and making inferences about the materials and the role they played in history.

Construct knowledge.

Including primary documents in the curriculum encourages students to discern the context in which they were created, synthesize information from multiple sources and form reasoned conclusions based on a variety of evidence.

Primary Sources and Social Justice

The types of higher-order skills supported by working with primary sources are critical to participation in civic life and have particular relevance for students investigating social justice issues and movements across disciplines.

The United States is the country it is today only because of the concerted efforts of engaged, informed citizens. Through the study of materials they left behind, students can really learn how it came to be. Analyzing primary sources requires students to observe and question each document or artifact, applying an informed skepticism about its purpose and the perspective of its creator(s). No single document tells the entire story of any event, and students seeking a definitive account will quickly find themselves weighing multiple, often contradictory, points of view. At the same time, many historical movements, events and even entire populations are woefully underdocumented; the few firsthand accounts or traces that do exist invite students to draw lessons from the silences as well as from the artifacts themselves.

Working with primary sources reveals the partial and incomplete nature of history and helps students see the power that they themselves have to complicate and expand current understanding of the past. In addition, close examination of the documents left behind by social justice advocates from history, such as crusaders for women’s suffrage or the anti-lynching movement, makes concrete the debates, tactics and personalities of earlier struggles. These traces and testimonies of activists from the past also empower students, reminding them that substantive social change is possible, however daunting the task may seem.

Skills and Techniques

Primary Source Analysis

A good way for educators to launch students into the exploration of primary sources is with a simple primary source analysis. The Library of Congress’ Primary Source Analysis Tool is a graphic organizer that helps students engage with any kind of primary source (e.g., a photo, map, movie or manuscript) and record their responses in a way that helps them build understanding.

When students analyze a primary source, they respond to it in a number of ways: observe the item, identifying and noting details; reflect on the item, generating and testing hypotheses about what they see; or, ask questions, leading them back to the item or launching new investigations and further research.

These responses don’t need to come in a particular order. A reflection leads to an observation, which might prompt questions, which could drive the student back to make more observations or reflections.

Encouraging student analysis through the lens of social justice invites them to reflect on point of view—not only that of the item’s creator but also of other individuals who interacted with the item. For example, consider questions a student might ask in response to this exhibit panel.

- Who are the children in this poster?

- Why do they look the way they do?

- What points were the creators of this poster trying to make?

- Why did they select the images they did?

- Why did they add the words they did?

- Who were they trying to reach with this poster?

By recording their thinking, generating a set of reflections supported by concrete observations and posing questions, students will create an intellectual foundation and a blueprint to guide further research.

Sourcing and Contextualizing

After students become familiar with primary source analysis, they can explore primary sources more deeply to seek answers. Two important strategies for engaging critically with a primary source are sourcing the document—thinking about the document’s creator—and contextualizing the document—situating it within time and place.

Working with primary sources carries with it the risk that students will assign the authoritative version of an event or situation to a single artifact or account. Even though primary sources were often created by participants in or eyewitnesses to significant events, each item still comes with its own context and history and requires students to evaluate it carefully in light of background information and other accounts. Students can ask a series of questions to help them source and contextualize:

- Who created the item?

- What role did the creator have in the event(s) referenced by the item?

- Who else played important roles in the event(s)?

- Who was the item’s intended audience?

- What was the item’s intended purpose?

- What was happening when the item was created?

The primary source itself and the bibliographic record may offer answers to some of these questions. (Most items in the online collections of the Library of Congress are accompanied by a bibliographic record. Look for the “About This Item” link.)

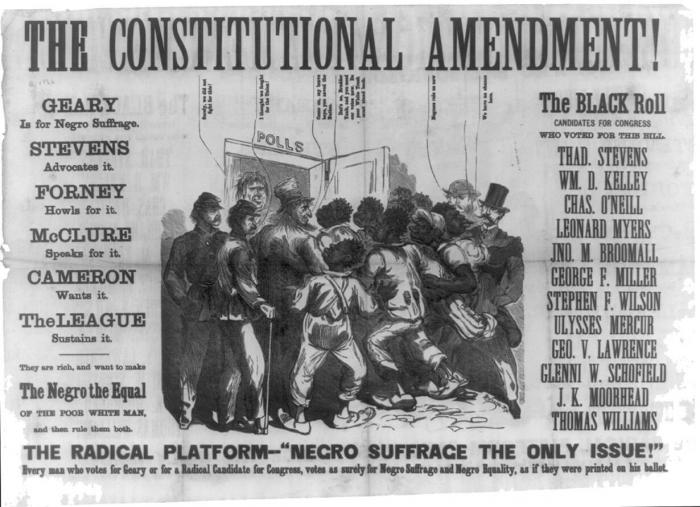

Consider this example of a sourcing and context exercise, based on the poster “The Constitutional Amendment!”

Educators could begin by inviting students to analyze the poster and asking how it adds to their understanding of the struggle for African-American suffrage in the years following the Civil War. Students could then apply the sourcing and contextualizing questions, and consult the poster’s bibliographic record to address any that remain unanswered.

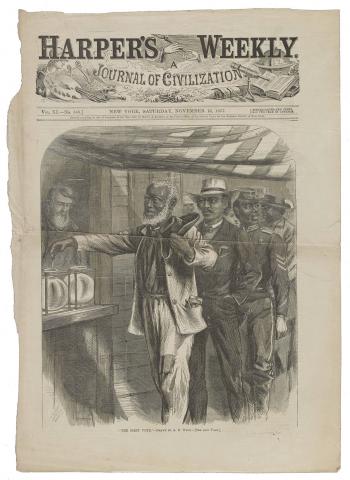

Students could then compare “The Constitutional Amendment!” to a contrasting document, the engraving “The First Vote.” They could begin the comparison by applying the same sourcing and contextualizing questions to “The First Vote” that they applied to “The Constitutional Amendment!”.

What additional details might students discover when answering questions about source and context? How does thinking about source and the context influence possible responses to the portrayals of African-American voters seen in the two images? What biases might they identify in both images? How could students use each of these documents as evidence to support their conclusions?

Sourcing and contextualizing historical artifacts that express a wide range of viewpoints help students deepen their understanding of an event or era. The questions that arise can also help them identify topics for further investigation across subject areas and disciplines.

Inspiring Research Questions

Historical primary sources often include long-forgotten language, attitudes and arguments, fostering curiosity among students that can be harnessed to direct and focus research.

After students analyze primary sources and investigate the sources and contexts of each, they will be prepared to formulate hypotheses and identify research questions to help drive their investigations. For example, students working with “The Constitutional Amendment!” and “The First Vote” could begin by asking how each documents advances a different position. They could also speculate about other possible positions in the debate over the rights of black citizens to vote and identify strategies for finding other primary sources that deepen their understanding of a complex period in U.S. history.

By developing research questions based on primary source analysis, students not only build their critical thinking and inquiry skills, but they may be inspired to apply what they’ve learned to social justice pursuits of their own. This is yet another way the “time machine” of primary sources can positively affect young people. Teaching with primary sources today may inspire the social justice leaders of the future.

Give your students the skills to read primary sources and better understand change throughout histoy.