An elementary student is sent home from her Texas school for wearing her hair in Afro puffs. A Louisiana senior is forbidden to wear her tux to prom. Three students in Pennsylvania are told they can’t use the bathrooms that match their gender identities. An Illinois school releases a dress code flier that features two young women, one labeled “distracting” and “revealing,” the other “ladylike.”

These are not isolated incidents. Similar stories have been reported in K–12 schools across the United States, and more unfold every day. Nor are they unrelated. Each situation was the result of a policy that treats students differently based on their identities.

These policies may be based on good intentions and rely on aspirational words like “respectable,” “safe” or “appropriate.” But when, for example, a hair policy disproportionately affects black students, it reveals a harmful bias: the perception that natural black hair is none of those things.

“[W]hile I teach my daughter that her natural beauty is perfect, this assistant principal is giving my daughter the message that her natural beauty is not good enough!” lamented the mother of the Texas student in an April 2016 Facebook post.

Gender-based dress codes and regulations preventing students from using gender-aligned facilities send a similar message to students: “Your identity is a problem.”

A Culture of Respect

Thomas Aberli, former principal at Atherton High School in Kentucky, says it’s important for school communities to consider what it really means—on a practical level—to respect someone whose identity is different from yours. Making sure school policies are inclusive is a reflection of “how we should treat one another in society,” he says.

In 2014, a freshman student at Atherton High School approached the teacher sponsor of the school’s gay-straight alliance looking for help telling the administration that she was transitioning. Under Aberli’s leadership, Atherton High School assessed how to make its bathroom, locker room and dress code policies more inclusive—a process that drew some criticism from the wider school community.

Opposition to the policy changes was more philosophical than practical, says Aberli. He recalls a conversation with one parent who said, “My daughter will not see a penis until her wedding night!” Aberli says he responded, “You know what, I have no control over that, but I will tell you that this policy is not going to permit your child to see sexual organs of any child of any gender in the restroom. That’s not what the intent of this is, and if that becomes an issue, then we can deal with that from a disciplinary standpoint.”

Opposition to the policy changes was more philosophical than practical, says Aberli. He recalls a conversation with one parent who said, “My daughter will not see a penis until her wedding night!” Aberli says he responded, “You know what, I have no control over that, but I will tell you that this policy is not going to permit your child to see sexual organs of any child of any gender in the restroom. That’s not what the intent of this is, and if that becomes an issue, then we can deal with that from a disciplinary standpoint.”

“By the end of a 15- to 20-minute conversation like this,” says Aberli, “most parents were like, ‘You know what? Not only do I respect the decision that you’re making, I feel like this makes our school safer for every child in the building.’”

Fear of the unfamiliar or threatening is often at the heart of policies that target traditionally black hairstyles as well. Attorney Anna-Lisa F. Macon, who has written about racialized hairstyle prohibitions, says educators may not be consciously targeting black students with their hair policies, but they need to stop and consider why a certain hairstyle seems disruptive or inappropriate. Is it truly disruptive, or is it just different? If the answer is different, says Macon, then “educators should adjust their perception of what is appropriate rather than requiring students to fundamentally alter their bodies and identities.”

Putting Policies in Context

School policies reflect the culture of a particular school and community, but they also—often inadvertently—reflect both the good and the bad aspects of our larger society.

Macon says problems arise when appropriateness is judged by schools in a way that favors certain ethnicities and races. “Race in America is about more than just skin color. It extends to certain traits and stereotypes that become inescapably intertwined with how we view certain groups,” she says. “Afros, dreadlocks, Afro puffs, cornrows, et cetera, are correlated with prototypical ‘blackness,’ and any associated negative connotations. In banning black hairstyles because of those subconscious associations, educators implicitly devalue black students.”

The impact of these policies goes beyond individual students. Denigrating hairstyles connected historically with marginalized groups sends the message that it’s OK for institutions to decide whose bodies are acceptable and whose aren’t.

Joel Baum, senior director of professional development at the nonprofit advocacy group Gender Spectrum, says the same principle applies when students aren’t allowed to use bathrooms and locker rooms that align with their gender identities. These restrictions can amount to an endorsement of discrimination by schools. “If the institution specifically says you don’t get to use the spaces that the other boys and girls get to use ... [i]t’s not just saying you’re stigmatized,” says Baum. “It’s saying, ‘We not only think you’re different—we think you’re dangerous. We think you’re a problem. We can’t expose the other students to you.’”

Baum finds gender-biased dress codes equally harmful, particularly if they imply that a student’s body is shameful or if they focus on preventing sexual arousal in boys. “Some kids have vulvas and some kids have penises. It’s OK to see one person’s belly button, but not the other’s?” he says. “And what are we saying to our girls? It further objectifies them, further sexualizes them.”

It is easy to get caught up in the intentions or conventions underpinning a given policy; taking a step back and thinking more broadly, say Baum and other experts, allows a school to evaluate whether its policies demand that students conform their bodies to a dominant-culture expectation. Such policies undermine the school’s obligation to support all students and guide them toward becoming adults able to function in and appreciate a diverse society.

Gender-based dress codes and regulations preventing students from using gender-aligned facilities send a similar message to students: 'Your identity is a problem.'

As Baum says, “We end up putting the onus on a kid wearing [certain] clothes, or trying to use the bathroom, or being trans, or wearing a particular hairstyle or wearing the hijab—or whatever it might be—that is ‘inflammatory’ for other people. Whose issue is it? … If you are not creating—[with] direct behavior and not just [with] your existence—a problem for another person, then why is it anyone’s business?”

Changing policies isn’t easy, but making both administrative and cultural shifts toward being more inclusive is possible. Aberli says, in the end, the Atherton High School decision-making council voted to change the school’s policies to be more inclusive; they’ve had no further opposition since the policy was implemented. The mother of the little girl with Afro puffs put several follow-up posts on Facebook thanking those who had helped further the discussion. She reported that her daughter’s school apologized and would be revising its dress code.

Aberli says he’s proud that Atherton embraced the idea that respecting individual differences is a strength rather than a weakness.

“When you feel and see that a variety of different life views provides a strength in a community as opposed to a divisiveness, then you’re better able to embrace dealing with change and dealing with how to manage a situation in which you have to address how we are different from each other.”

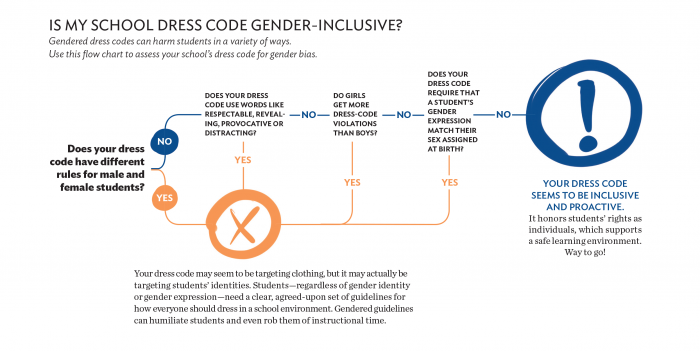

Is Your School Dress Code Gender-inclusive?

Use this chart to assess it.

But It’s Distracting!

It’s not uncommon to hear aspects of a student’s appearance or behavior dismissed as distracting or inappropriate. Because these assertions are so vague, they can be difficult to rebut. Try these suggested responses.

Complaint: Cornrows glorify “street” culture.

Response: This coded language associates a traditionally black hairstyle with criminal behavior. Remind the speaker that hair doesn’t “do” anything, and that the associations we have with hairstyles are contextual; if we don’t examine these associations, we run the risk of communicating our biases to students. If a student is engaging in criminal behavior, address the behavior. Being overly controlling about a student’s self-expression is counterproductive when it comes to helping them feel valued and invested in school.

Complaint: That outfit isn’t “ladylike.”

Response: School communities have a right to agree on and enforce dress codes—just not dress codes that have different requirements for some kids than for others. Encourage self-reflection. Ask, “Do our clothing policies differ based on gender?” “What do they imply about our society’s gender norms?” “Do our policies objectify young women by sending them the message that their bodies are inherently sexy?” “Do they reinforce rape culture by implying that young men are unable to control themselves?”

Complaint: I’m uncomfortable being in the bathroom with a student who is transgender.

Response: Point out the difference between accommodation and discrimination. If someone is uncomfortable being in a shared space—for whatever reason—give them the option of a more private facility. Just remember that their discomfort isn’t justifiable cause to force another student to use a different bathroom or locker room.