Erected in New Orleans in 1891, the Liberty Monument rises in stone, a visible reminder of this nation’s struggle with its racist past.

The Liberty Monument commemorates the Battle of Liberty Place, an 1874 skirmish between the so-called White League and the racially integrated Reconstruction state government. The spirit behind the obelisk is the same spirit that ushered in the Jim Crow era.

In the more than 120 years since the monument’s construction, inscriptions have been removed and rewritten. People have called for its removal or destruction. The Ku Klux Klan has planned rallies around it. It was placed in storage during a street improvement project and then, following a federal lawsuit by monument supporters, re-erected in a less prominent location.

The latest inscription reads:

In honor of those Americans on both sides of the conflict who died in the Battle of Liberty Place. A conflict of the past that should teach us lessons for the future.

“What these lessons might be is left wholly unarticulated,” writes Sanford Levinson in his book Written in Stone: Public Monuments in Changing Societies. “The voice of the tutor is quite muffled, leaving the monument to speak for itself without further elaboration.” Levinson is also a professor of government at the School of Law of the University of Texas at Austin.

Across the United States, there are statues and memorials that illustrate complex lessons of muddled history and regional pride. The challenge for educators is to help students “hear” what these monuments are saying—both intentionally and unintentionally.

In the South, for instance, Confederate memorials are common. A bust of Confederate Civil War General Nathan Bedford Forrest—a slave trader and early KKK member—once stood outside a city government building in Selma, Ala. A decade ago, protests prompted the relocation of the bust to a city cemetery, where it later disappeared, presumably stolen. Recent plans by a Confederate-heritage group to replace the bust have been met with more protests, including heated public testimony during city council meetings.

At one such meeting in September 2012, Selma resident Rosa Monroe asked those assembled, “How are we going to teach our kids anything if we give praise to this man?”

Of course, the dilemma of how to teach the history of monuments steeped in hate and oppression is not confined to the South. Monuments memorializing battles with Native Americans and white exploration of the American West have sparked controversy because of their one-sided version of history—glorifying white Americans and painting Native Americans as savages.

One Connecticut town relocated a statue of Capt. John Mason from its original site, a former Pequot village where Mason led a brutal 1637 raid. The village land is considered sacred by the Pequot Tribal Nation; along with others, the Nation has pushed to have the monument moved to a less controversial spot.

In recent years, stronger efforts have been made to ensure new monuments are inclusive, but those endeavors often fall short. At a 2010 dedication of a Lewis and Clark monument at Dismal Nitch on the Columbia River, for example, a member of the Chinook Indian Nation reminded those in attendance that “Dismal Nitch” is the name given to the notoriously stormy inlet by white explorers. “For thousands of years,” he said, “we just called it home.”

Tips for Teaching About Controversial Monuments

DO promote open discussion.

DON’T ignore connections to hate and oppression.

DO examine monuments in the context of today’s society.

DON’T push students to make a final judgment.

Whose History?

Daniella Garran, a seventh-grade social studies teacher in Massachusetts, says monuments, statues and memorials are a crucial part of her lessons. In the classroom, she uses two-dimensional images, but when possible, she takes her class to visit actual monuments.

In one lesson, she asks her students to put together a proposal for a Holocaust memorial. Where would it be located? Who would fund it? What would its message be? What would it look like?

“You have to analyze the politics behind monuments, whether it’s civil rights or Vietnam or Mesopotamia,” Garran says. “Who is telling the history? When is it propaganda? What is the subtext? Artistic choices—whether in a painting or a sculpture—are deliberate, and we have to ask ourselves what each choice means.”

Did you know?

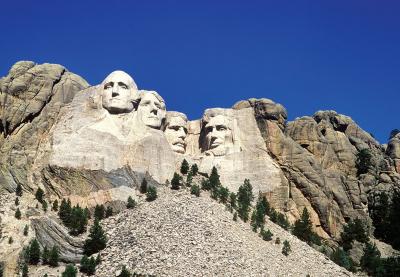

Mount Rushmore

Did you know that this well-known monument was built on land (considered holy by many American Indians) that was seized from the Lakota Sioux without their consent? Or that its sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, had ties to the Ku Klux Klan?

Eternal Questions

A unique aspect of the history of the United States—compared with, for example, the former Soviet Union—is that we are not a nation that topples its statues when leadership changes.

Levinson spends a good deal of time with this dichotomy in his book, Written in Stone. He urges American history teachers to explore with students why statues of Stalin in Russia and other Central and Eastern European countries were torn down.

In this nation, we tend to move our troubling monuments to less visible locales or revamp them, adding cultural context and interpretation. But we don’t see masses of people with ropes and winches tearing down historic statues.

James Percoco, a retired history teacher, likes it that way. “Don’t erase the past,” he says. “Interpret it.”

Percoco believes that spending time in our historic discomfort is a good and valuable thing. He urges educators to be open to discussions about monuments that don’t have clean or easy answers—or perhaps any answers at all.

“It can be tense; these are difficult issues,” he says. “In my classroom, I would have students whose ancestors fought in the Confederacy, students whose ancestors fought for the Union and black students. The tension is right there; it exists.”

That, Percoco says, is why conversation about these controversial monuments and memorials is necessary.

“It’s not about finding the answer,” he says. “It’s discussion, conversation and dialogue about, really, what are eternal questions. All these issues are central to who we are as Americans.”

Closing the Gap

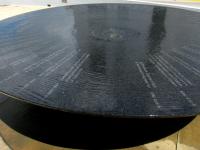

There is a gap in the timeline of the Civil Rights Memorial outside the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Ala. Sculptor Maya Lin put it there on purpose.

The memorial honors those who died during the civil rights movement. Many visitors have never heard the names on the memorial—the names of foot soldiers who lost their lives during the movement. But some know the stories. They rub their hands along the black stone, feeling the water flow down around their fingers.

Each year, more than 20,000 people visit the memorial, which focuses on the period between the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. Lin’s gap comes after that.

Lecia Brooks, outreach director at the SPLC, sometimes leads discussions with groups of students at the memorial. “I call out the gap,” says Brooks. “I remind them that this work is unfinished, and then I ask them, ‘Where are you in the movement?’”