In May 2013, a group of teachers and students traveled from Salamanca, N.Y., to New York City to sit in a session room at the United Nations. School trips to the U.N. are not unusual given the number of Model U.N. conferences and field trips that take place every year. But this trip was different.

Most of these students were Seneca Indians. They also were members of a student group—the only one of its kind—about to address the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII), described on its website as “an advisory body to the [U.N.] Economic and Social Council with a mandate to discuss indigenous issues.”

On that day in May, as they listened to addresses from indigenous leaders from around the world, the Salamanca students recognized concerns and challenges similar to those experienced every day in their own backyards. As he listened, Nicholas Cooper—a high school senior at the time—felt increasingly nervous. He was waiting to stand and speak himself, to deliver a speech the group had been preparing for months.

In the Beginning

In 2009, there was no group, no speech, no trip planned to the U.N. That changed when Suzanne John-Blacksnake, a guidance counselor at Salamanca High School, saw a need for additional support for her Seneca students who were dropping out and repeating grades at higher rates than their peers. “We’re always looking for in-school support and programs that might interest our students and try to keep them more involved in school,” she says.

John-Blacksnake and the other Salamanca High staff wanted to motivate their students through programming that tapped into their culture and community. The city of Salamanca is located entirely within the boundaries of an Indian reservation—the Allegany Reservation of the Seneca Nation. The town has a unique cultural history but has also struggled with poverty, land disputes and Native/non-Native relations. Seventeen percent of Salamanca residents are Native.

John-Blacksnake reached out to Gerald Musial, a Seneca history and global history teacher, and Rachael Wolfe, a Seneca language and culture teacher. The three teachers knew they wanted a club that would connect students to international politics and the larger world, which, in many schools, would mean a Model United Nations club. But Model U.N. does not directly connect to topics that would resonate with the culture of Salamanca’s Seneca students. To make the club culturally responsive, they needed to focus on such issues as treaty rights, taxation problems and condemned land use on the reservation—issues that are important to indigenous people around the world. John-Blacksnake and the other advisers decided to create the first Model United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (Model UNPFII).

“We wanted to try to build future leaders ... and give them some ways to fight in another arena, on an international level,” says John-Blacksnake.

John-Blacksnake and her colleagues based their Model UNPFII on the actual Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, which meets annually for two weeks at the U.N. to discuss the problems faced by indigenous cultures and advise the U.N. The Salamanca High School students were already familiar with the relevant legal, educational, human rights and social issues—they lived them. The Model UNPFII would allow the students to tie their personal experiences to the global community and look for solutions there.

Getting Started

The Model UNPFII advisers kicked off the new club with an explanation of the U.N. and the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and an overview of some of the relevant issues indigenous populations face, both locally and globally. They also taught how the Permanent Forum functions as a body and how it makes decisions.

“To teach indigenous issues, you must use indigenous understanding of the world as a method of transmitting ideas,” Salamanca teachers wrote in a paper presented to the National American Indian Enrollment Association conference in 2012. Musial says, “[The] idea is to be of one mind,” meaning that, rather than relying on majority rule, everyone must agree to move forward. The students were familiar with this idea—the Seneca Nation has used the process of unanimous consent—and adopted it as their decision-making method.

We stand here as a group of youth who are screaming to all other indigenous youth that yes, we are amazing. We can see it, but please help us make others believe it too.

The inaugural Model UNPFII members researched indigenous issues in each of the six regions identified by the UNPFII. Through interviews with elders and Faithkeepers and other primary research, the students began making connections to the concerns of indigenous people in their own community—and planning how they could act for change.

Musial knew, from an initial conversation with the Secretariat of the Permanent Forum Broddi Sigurðarson, that going to the U.N. was a possibility. Operating with such a trip in mind helped the students remain focused. New York City was where their “model” experience would cross over into real life. Together, they began crafting recommendations to the Permanent Forum for how they could help indigenous youth. They made their first trip to the U.N. in May 2011.

The Speeches

Nicholas describes a whirlwind of work leading up to each of the three U.N. trips the group has now taken. “We’ll outline, take notes, think, collaborate,” Nicholas says. Community members offer suggestions about what the group could add or take away from the speech. The students then go back and discuss—to the point of unanimous agreement—what content should remain in the final draft. “It mean[s] sitting with students for … hours and discussing every line in the statement,” says Musial.

Nicholas was selected by his peers to deliver the Model UNPFII speech in 2013. When he stood at the front of the U.N. conference room, he made several recommendations to the Permanent Forum for how it could empower indigenous youth who face high drop-out rates, suicide, substance abuse and domestic violence. He asked the Permanent Forum to “create youth training programs that allow indigenous youth to interact with the U.N. systems.”

“The simple answer is that indigenous people need empowerment,” he told 1,500 participants from around the world. “We stand here as a group of youth who are screaming to all other indigenous youth that yes, we are amazing. We can see it, but please help us make others believe it too.”

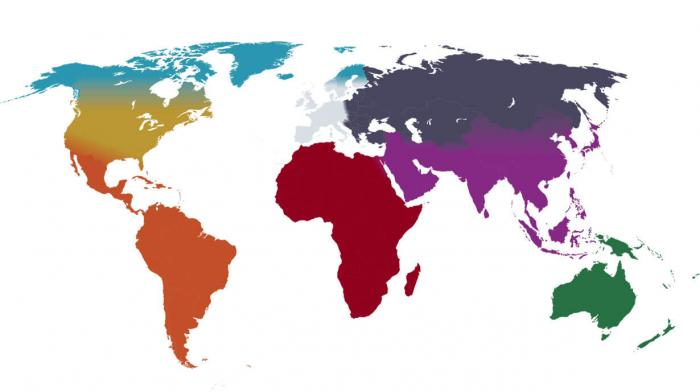

The UNPFII welcomes representatives of indigenous populations from seven regions: 1) Africa; 2) Asia; 3) Central and South America and the Caribbean; 4) the Arctic; 5) Central and Eastern Europe, Russian Federation, Central Asia and Transcaucasia; 6) North America; 7) and the Pacific.

The Lasting Impact

Today, three years into the Model UNPFII program, Nicholas observes, “We’re students but we’re not just your typical high school students. ... Being a part of [Model UNPFII] held us to a higher standard.”

That standard has risen steadily each year as Salamanca watches its young people become experts in local and global issues and solve problems with indigenous people from around the world. They’ve raised funds. They’ve reached out to other schools. They’ve traveled to Native historical sites all over the Northeast. Their relationship with the Permanent Forum has bloomed. In 2012, U.N. representatives visited the school to train Model UNPFII participants about indigenous issues, and UNICEF has elicited Model UNPFII input on a publication designed to educate indigenous youth worldwide.

Staff members at Salamanca High say participating in Model UNPFII has been life-changing for many students. Nicholas Cooper says being around other indigenous peoples has encouraged him to move further in his education and helped him become the first in his family to go to college.

“The values that [Model UNPFII] taught me and speaking at the U.N. will help me no matter what I decide to do,” he says. He just finished his first semester of college. Stories like his are becoming more common as Model UNPFII continues to grow.

“As people say around here,” says Musial, “our kids are fierce.”

Inspire students to become social activists!

- Talk to students and the community to understand what issues are most important to them.

- Empower students to speak from their experience and to reach out to other community members.

- Provide support and resources, but let the students lead the way!