Joey, now in 11th grade, is thriving at the Bronx Design and Construction Academy (BDCA). That fact is far more remarkable than it may at first seem because most other schools would have suspended, expelled or otherwise pushed Joey out before ninth grade was over.

BDCA is a small New York City public high school committed from its inception to using an inquiry-based, restorative and accountable approach to discipline and student support. It’s a different model than Joey was used to, and during that first year, he was, in the words of his teacher and advisor Nathaniel Wight, “struggling to adjust.”

That struggle put Joey right at the heart of BDCA’s discipline policies. At BDCA and other schools that employ restorative discipline practices, when students engage in behaviors that violate classroom or schoolwide norms, agreements and expectations, educators intervene in ways that keep students engaged in classroom and school life as they learn ways to self-correct. For the small percentage of students who exhibit severe behavioral difficulties, teachers and school administrators involve social workers, school counselors and school psychologists to offer appropriate levels of support. Accountable consequences aim to restore students to their classrooms and school communities rather than punitively and pointlessly suspending them or, as often happens, criminalizing their behavior.

A restorative and accountable approach to discipline and support begins with a commonly agreed upon code of conduct describing a safe and respectful school culture; outlines explicit student expectations, rights and responsibilities; and calls for mutual accountability among all adults to support students’ academic, social and emotional development. When students violate this code of conduct, disciplinary consequences and interventions require students to own the problem, reflect on the impact of their behavior on themselves and others, and understand why the behavior was unacceptable or unskillful.

Restorative inquiry, a nonjudgmental discussion technique, allows an educator to listen to and understand a student’s experience and then guide him to examine who was impacted by his actions and commit himself to words and actions that will enable him to right himself, repair the harm he has done to others and restore his good standing in the community. This can mean that students sometimes need to make things right not only to others but also to themselves.

Carol Miller Lieber, a writer and consultant with Educators for Social Responsibility, reminds educators that “[n]ot all interventions are the result of interpersonal conflict. Many students experience problems related to self-management, personal distress or family crisis.” Because of this, it’s important to take an approach (such as restorative inquiry) to student discipline and support that is both socially restorative and self-restorative.

Engaging Schools

Based in Cambridge, Mass., Engaging Schools works primarily with urban middle and high schools to maximize the capacity of educators and school leaders to create engaging schools and classrooms that foster academic achievement, healthy social and emotional development and postsecondary success. ESR collaborated with BDCA to implement Guided Discipline, a classroom-level system of discipline and student support that is aligned with Getting Classroom Management RIGHT: Guided Discipline and Personalized Support in Secondary Schools, by Carol Miller Lieber.

A key element of the restorative and accountable approach emerged from the federal initiative called Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS)—a three-tier system of graduated supports and interventions that meet the needs of all students. Universal supports and practices (tier one) promote positive behavior and prevent minor disciplinary infractions from becoming major disciplinary incidents. In PBIS’s second and third tiers or stages, more targeted and intensive interventions are provided for students at greater risk.

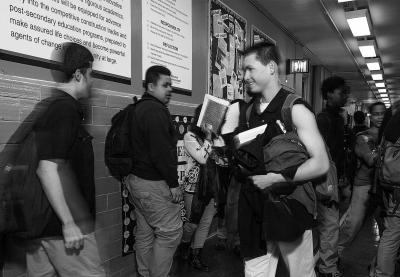

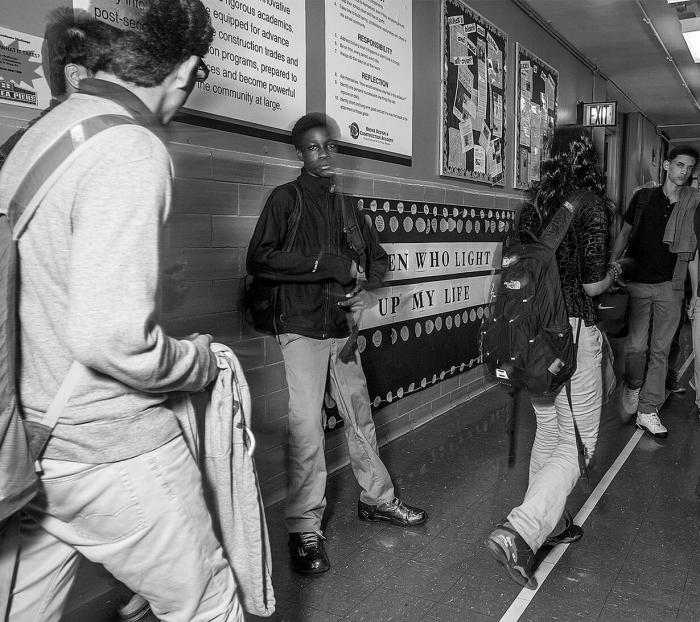

All of these elements of a restorative and accountable approach to discipline and student support inform the school culture at BDCA. The BDCA’s code of conduct, called the BDCA Ways, is explicitly taught during student orientation and advisories and posted in the hallways and in every classroom. Adam Paredes, dean of students for BDCA, notes, “The BDCA Ways are the core of our school culture—without them, we would have been lost.”

We create a culture in which it’s an honor to be in class. We’re not going to suspend students, but we will hold them out of class. If they want to go to class, they have to earn it by correcting before moving forward. They become part of the solution.

At BDCA, teachers also note student disengagement in an online behavior log that the dean of students and advisors review daily. Patterns quickly emerge, and when administrators greet students as they enter the building the following day, they can address situations before they escalate into days or weeks of learning loss. “We have many students struggling as they adjust to high school and our expectations here,” says Paredes. “We get a lot of behavior logs going at first, but for most students, the commitment to keeping them part of the community works, and we find that we’re seeing behavioral progress significantly in short order.”

In classrooms, BDCA uses universal practices that build a coherent community of learners based on cooperation and respect, such as effective teacher talk. In Getting Classroom Management RIGHT: Guided Discipline and Personalized Support in Secondary Schools, Lieber describes effective teacher talk as the use of “verbal prompts you use to respond immediately to problematic behaviors in ways that invite cooperation and self-correction, help students get back on track, and prevent potential confrontations and power struggles.” This might mean a quick personal check-in with a student who has lost focus or a reminder to review classroom expectations when small groups are not managing their time and tasks skillfully. Effective teacher talk takes advantage of big and small opportunities in which students can take responsibility to change their behavior in the moment—and stay in class.

BDCA also supports students who continue to demonstrate harmful or disruptive conduct after repeated invitations to reflect and self-correct. With these students, the school focuses on accountable consequences. Aimed at restoring one’s good standing, repairing damage that’s been done and helping students learn new behaviors and ways of thinking that will support them in the future, accountable consequences are carried out by students with adult support to correct and change unwanted and unacceptable behaviors. Consequences and interventions are presented as outcomes of the choices students make and the skills they need to learn. By investing time and effort in consequences that are logical, reflective and corrective, students account for their unwanted behavior.

One fundamental, inquiry-based consequence schools can use is restorative conferencing. Conferencing allows students to resolve interpersonal problems so they can resume attending class in good standing. When a cohort of students or an entire class needs to address and resolve a problem, a group conferencing format can be useful with the support of a teacher or other professional to facilitate the conversation.

At BDCA, when Joey persisted with disruptive acts, such as writing on the walls, teachers sent Joey out of class to an administrator, who helped him reflect on what happened. Paredes says, “We create a culture in which it’s an honor to be in class. We’re not going to suspend students, but we will hold them out of class. If they want to go to class, they have to earn it by correcting before moving forward. They become part of the solution.” Joey took responsibility by initiating a conference with the teacher whose class he had been asked to leave. During the conference, Joey and his teacher discussed what had happened and made a plan that allowed him to rejoin the class.

In schools that use restorative and accountable discipline and student support, students necessarily take an active role. Discipline is not something that is externally imposed. Instead, students engage in inquiry and must have a voice in determining next steps and consequences in a context of support, strong relationships and effective communication. “We put the responsibility on the shoulders of students to correct mistakes when they happen,” says Paredes, “and we are fully committed to their success.”

As Wight notes, “Joey had constant feedback from school staff members. He experienced our ‘never give up attitude,’ and through it all, we made sure we were working with him, not talking down to him. We were determined to pull him in, not push him out. We choose language that empowers students, that doesn’t minimize or shut them down.”

Of course, establishing restorative and accountable discipline and student support within a school isn’t easy, and few schools have the opportunity that BDCA did to start with these ideas from the ground up. But even small changes can make a big difference. Effectively implementing strategies such as co-creating classroom expectations and agreements with students, employing effective teacher talk and using early warning systems can shift the dynamic in a classroom. Schoolwide changes require more coordination, planning and effort but can be transformative, especially for students who face greater intra- and interpersonal challenges.

Get Started Using Restorative Inquiry

Whether social restoration or self-restoration is your goal, these questions will help you guide the conversation.

Social Restoration

- Tell me what happened. What was your part in what happened?

- What were you thinking at the time?

- How were you feeling at the time?

- Who else was affected by this?

- What have been your thoughts since?

- What are your thoughts now?

- How are you feeling now?

- What do you need to do to make things right? Repair the harm that was done? Get past this and move on?

- What can we do to support you?

- What might you do differently when this happens again?

Self-Restoration

- Tell me what’s been happening. What has not been working for you?

- What are you thinking about this situation?

- How are you feeling about this situation?

- How is this getting in the way of your learning? Feeling okay about school? Being the person you want to be at school?

- What do you need to learn/to do to make things better? Make things right? Reset and get back on track?

- What can we do to support you?

- What might you do differently the next time you find yourself in this situation?