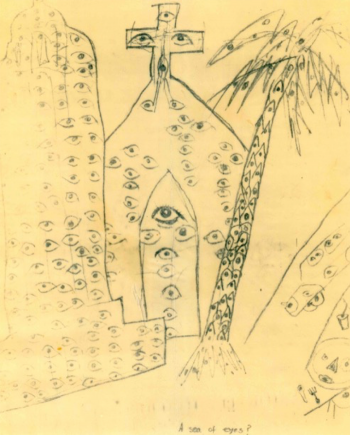

In the drawing, eyes are everywhere: They crowd the doorway of a church and ornament the hood of the car swooping down beside it. They peer from the stones of buildings, from steps, from the roots and fronds of a palm tree.

The artist, Hari Singh Everest, was born in 1916 in what was then British India but is now Pakistan. Like millions of others, his family was forced to relocate during the partition of 1947 following the end of British colonial rule. It was in 1956, two years after he came to the United States, that he drew “Stanford: A Sea of Eyes?”

Everest earned his master’s degree at Stanford, studying communications while working on farms to support himself. His turban and beard not only attracted attention at the school but prevented him from getting a job in the profession he trained for. Professor Nicole Ranganath, the curator and historian at Pioneering Punjabis Digital Archive, recounts a conversation between Everest and an administrator at Chico State after Everest applied for an academic job as a professor. “You're overqualified for this position, but you're not an all-American boy.” This despite Sikhs having been in the United States since the late 19th century. (Sikhs, along with other South Asians, were denied citizenship between 1923 and 1946).

Eventually, Everest became an elementary school teacher—the first South Asian teacher in his district. He taught there for 20 years.

During the course of his career, Everest become a prolific writer, a poet, a community leader, the president of United Sikhs for Human Rights, an editor of magazines and a volunteer at many institutions including the California Department of Education Ethnic Advisory Council and the Sutter County Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Commission. But, despite his successful immigration story, he was never regarded as fully American to many who encountered him.

Harassment, Hate and Bias

It’s been 60 years since Everest drew the sea of eyes. But the ignorance and suspicion the eyes represent is still prevalent today—and it often falls on Sikh families and communities to do the outreach required to create inclusive spaces.

There’s clearly a need. According to the 2013 report Turban Myths, published by the Stanford University Peace Innovation Lab and the Sikh American Legal Defense and Education Fund, there is a profound lack of knowledge in the U.S. about the Sikh community and widespread bias against those who wear turbans. Key findings of the study reveal:

- 49 percent of Americans believe that “Sikh” is a sect of Islam (it is an independent religion).

- Only 21 percent of respondents identified India as the geographic origin of Sikhism.

- When shown a photograph of a Sikh man, about 70 percent of respondents could not correctly identify his religion.

And it’s not just a lack of information. One in five respondents in the same study said that when they saw a stranger wearing a turban it made them feel “angry” or “apprehensive.” Together, this fear and ignorance have resulted in Sikhs being targeted for hate and bias crimes. From the first Sikh victim of the rash of post-9/11 hate crimes to the massacre at a Milwaukee gurdwara in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, in 2012, Sikhs have been paying the price for a toxic combination of ignorance and religious intolerance for decades.

The same hate and bias is evident in classrooms across the nation and has been for years. Prabhu Singh Khalsa, who attended school in New Mexico in the 1990s, remembers, “My twin brother and I were the only Sikh kids and the only Anglo kids in our school. We faced pretty much hourly harassment about our patkas (turbans) from 2nd grade to 6th grade.” Vikram Singh Mangat, who attended schools in multiple districts in the Northeast in the 2000s, says the bullying he faced—and the schools’ poor responses to it—have had lasting effects. “It was mostly in middle school where I got targeted the most,” he recalls. “I was called Bin Laden, terrorist, stuff like that, and it hurt. It was a diverse school, and maybe other kids went through this also. But the school culture was such that it taught me to keep things to myself, and that really affected my mental health later on in life.”

Consequences for Sikh youth continue to be devastating. Go Home, Terrorist, produced by the Sikh Coalition, reports on bullying against Sikh American schoolchildren based on surveys in Massachusetts, Indiana, Washington and California. These surveys reveal that turbaned Sikh children are bullied at more than double the national average. Name calling, psychological abuse and even physical violence have become rites of passage for these children; more than 50 percent of Sikh students report being bullied in school.

Sarabjeet Saluja Bhutani, a counselor in the Maryland public school system, understands how difficult this can be for children and their families. “It’s sometimes very hard for Sikh kids to share with their parents [that they are] being bullied, knowing their parents also face harassment.” She shares a story from her own family: After her son told her that a teacher repeatedly referred to him as a girl (presumably due to his uncut hair), Bhutani decided to address the confusion head on. “This was a prompt for me to engage the teacher [and] the principal and start courageous conversations to answer questions swirling in our heads that we adults hold ourselves from asking,” she explains. “I was able to do presentations for the school, teaching and administrative staff introducing our American story.” Bhutani's efforts led to school staff taking a Saturday morning tour of a gurdwara, dialogue with Sikh students and the experience of wearing a Sikh turban.

Striving for Visibility

Sikh Americans like Everest and Bhutani aren’t alone in their fights against ignorance and bias. Every year, across the country, Sikh parents and guardians visit classrooms to answer questions from students and teachers and to introduce their culture, their faith, their long hair, their turbans—to introduce themselves and their way of American life.

These conversations can be effective, but they also have their limits. Their impact is hyperlocal. They rely on the availability and initiative of parents and guardians. And, perhaps most importantly, they shift the responsibility for creating inclusive classrooms away from schools and educators and drop it on the shoulders of families whose members may be struggling to be included.

For educators committed to culturally responsive and sustaining teaching, family and community involvement is only one piece of a larger picture. The good news is that resources abound for those willing to fight for equity in their classrooms, schools and districts.

Classroom-ready materials are widely available to those interested in educating students about Sikhism.

- The Kaur Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to teaching K-12 students about Sikh Americans, offers free educator resources for teachers of all grades, including Cultural Safari, a 17-minute video with accompanying elementary and secondary Teacher Resource Guides. The curriculum includes quizzes, essays, group activities and research assignments.

- United Sikhs, a global disaster relief and human rights advocacy nonprofit affiliated with the United Nations, has created lesson plans for teaching middle-grades students about the teachings of Sikhism and the lives of Sikh Americans within the context of civil rights.

- And, for high school teachers, U.C. Davis’s Pioneering Punjabis Digital Archive offers a wealth of primary documents and lessons about early Sikh Americans, including Hari Singh Everest.

Educators looking for texts and videos to engage their students and provide mirrors of and windows into Sikh culture and experience also have a range of excellent options.

- Sikh Coalition, the largest Sikh American advocacy and community development organization in the United States working to secure safer and more inclusive schools, offers text and video recommendations for students in all grades. Teaching resources include Who Are the Sikhs to start discussions in elementary, middle and high school classrooms about Sikh communities in the United States.

- For older students, Waking in Oak Creek, a documentary and lessons about the 2012 murder of six worshipers at a Milwaukee gurdwara by a white supremacist, offer insight into the hate and bias faced by Sikh Americans.

- Sikh Kid to Kid (SK2K) is a unique youth-run organization based out of Maryland that helped create a program to train teachers in religious literacy. The 45-hour course features lessons from the Religious Freedom Center, covering five major world religions, and rewarding teachers with three professional development credits in Montgomery County. They also offer video content to highlight basic facts about the Sikh faith.

Many of these organizations have also created resources to support education and fight bias at the school and district level.

- Sikh Coalition provides information about the bullying of Sikh children in schools with periodic reports providing a fresh lens into the extent of the challenge faced by these students.

- Sikh Coalition also advocates for the inclusion of Sikhs in state social studies standards. Colorado recently joined New Jersey, Texas, New York, California, Idaho and Tennessee in including accurate information about Sikhs in their standards.

- For individual professional development or community reading programs, educators might try the book Bullying of Sikh American Children: Through the Eyes of a Sikh American High School Student by Karanveer Singh Pannu, a graduate of New Jersey public schools. Including personal narrative, stories of fellow Sikh students and extensive interviews with experts, the text began as Pannu’s high school capstone project.

Complicating the Narrative

The most effective tools in the fight against Sikh stereotypes may well be stories, such as those found in the video series Digital Stories from the Iowa Sikh Association. Produced in 2013, these short films feature five young Sikhs explaining aspects of their experience and identities. In the first video, 13-year-old JJ Singh Kapur recounts the day he and his family were harassed by teenagers at a restaurant. “I will never forget my father’s eyes,” the teen says, “Filled with anger, but not fear. I wish I was fearless like him. But I’m not there yet.”

Last October, Kapur—now preparing to attend Stanford University, Hari Singh Everest’s alma mater—competed in the National Speech and Debate Association’s 2017 Original Oratory competition. Speaking to a rapt audience, Kapur explains that his father confided he had felt fear following September 11, that he’d told his son he was afraid “that Americans would ... see my father’s beard and turban and think, ‘terrorists.’ In the aftermath of 9/11, our grieving nation quickly adopted what author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie calls the danger of a single story—a simplified narrative where all Sikhs and Muslims are national villains.”

Closing his speech, Kapur calls on his audience to reject that “single story” in favor of a more realistic, more nuanced one, one that “recognizes life’s complexities.” In short, a story that dedicated teachers—supported by the right resources—can help their students understand.

Kapur is a captivating speaker. He’s charismatic and funny; at one point, he even dances. By the time the audience breaks into whoops and applause at the end of his speech, it’s clear he’s won. And every eye is on him.

Vishavjit Singh is a cartoonist, writer, diversity speaker, creator of Sikhtoons.com and Creative Arts & Diversity fellow at Sikh American Defense & Legal Education Fund.

Facts About the Sikh Faith

The Sikh faith originated in the Indian subcontinent in the 15th century. Now, there are 20 millions Sikhs of many different nationalities living worldwide.

Sikhism is now the fifth-largest religion in the world.

When accepting the Khalsa initiation into the faith, Sikhs agree to live by the principles of truth, contentment, humility, compassion and justice.

Sikhism is built on the belief that “We are all created equal.” To see the universal energy in every living being is the foundation of the Sikh way of life.

One way Sikhs honor this belief is through Langar. This is the name of the community kitchen in every gurdwara (Sikh house of worship) and also of the free meals Sikhs serve outside the gurdwara to anyone who is hungry—regardless of their race, color, gender or background.

The belief in equality is also evident in the common use of the names “Kaur” (for women) and “Singh” (for men), which are used as last names to replace surnames that often signaled one's place in the caste system.

Sikh Gurus acted on this belief by emancipating women from discriminatory practices of sati (widow suicides) and outlawing female infanticide. Women were given leadership roles and some led men in battle.

The turbans worn by Sikh men and some women are another example of the belief in equality. Because turbans were used as a signifier of royalty and tools of discrimination for centuries in South Asia, the Sikh faith mandates for all of its adherents to don the turban as an act of ultimate equality and humility.

Baptized Sikhs wear five articles of commitment to their faith, sometimes known as the “five K’s”: kesh (uncut hair), kara (a metal bracelet), kangha (a small wooden comb), kirpan (a religious article resembling a knife) and kachera (long cotton undershorts).

This toolkit provides recommendations for talking with students in elementary, middle and high school about identity, representation and Sikh experience in the United States.