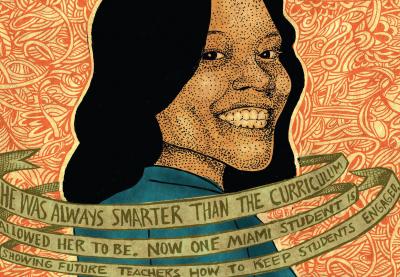

Tranette Myrthil’s favorite subject is English. But during her junior year of high school, the class she loved had become drudgery. There were no discussions about the stories students read in class. There were no explanations of why answers on assignments were wrong. “It was come in, grab a book, do this page,” says Tranette, the daughter of Haitian immigrants.

When a test came around and students still didn’t understand something, Tranette says, “it was too late.”

Tranette never felt comfortable approaching the teacher and went to another English teacher for advice instead. Her classmates just got angry.

Tranette knows teachers can do better. And she has told them so.

Driven by her disappointment — and motivated by teachers who approached instruction very differently — Tranette created a lesson plan last year to give teachers strategies to engage their students, no matter their income or race.

Her ideas were so inspiring that in April of this year, as a senior, she was awarded the Princeton Prize in Race Relations.

“Something very important to me is, you have to get the students involved,” she says. “You have to interact with them. There has to be some kind of discussion.”

Tranette was a student at Miami Edison Senior High School, which serves the Miami’s Little Haiti neighborhood, one of the poorest communities in Florida.

During Tranette’s junior year, education professors from Florida International University in Miami came to her American History class two or three times a week for most of the school year. They taught students about the evolution of American education — everything from Brown vs. Board of Education to Mendez v. Westminster.

Then they asked for students’ ideas about how to engage peers who historically had been marginalized. Louie F. Rodriguez, a professor of education leadership and policy studies, ran the program with an FIU graduate student. He chose Tranette’s school for a reason: he says he wanted to learn about student engagement by listening to students at “one of the most notorious high schools in the county.”

A Tragic Outcome

Public perception has indeed been a problem for Edison. According to the state of Florida, the school is a near “failure.” In 10 years of grading schools based on test scores, Edison has never ranked higher than a D.

The school’s reputation hit a low point last year, when a protest in the cafeteria escalated into a melee that ensnared several hundred students and spilled into the hallways. More than two dozen students were arrested, including Tranette, a mild-mannered teenager who looks younger than her age.

Charges against most of the students, including Tranette, were eventually dropped, but the school’s reputation was further tarnished. The fracas happened right before the tests in reading, writing and math that determine school grades. Instead of building on the prior year’s D, the school receded to an F later that spring.

To Tranette, the whole conflict was the tragic outcome of an honest effort to make a difference. The conflict began when a group of students decided to protest the treatment of a student by a school administrator. Witnesses gave different accounts about the pair’s confrontation, with police reports saying the teen grabbed the administrator and some witnesses saying the opposite.

When the incident happened in February 2008, students’ minds were fresh with lessons about civil disobedience. They made posters and took them to lunch the day after the scuffle, but instead of a peaceful protest, the demonstration swelled quickly into a tangled physical rumble.

“The whole protest situation, I didn’t involve myself for it to turn out the way that it turned out,” Tranette says. She was the fifth to be arrested.

“Students have a voice. We all just wanted to be heard.”

A New Conversation

The protest only made Rodriguez’s efforts more timely. It fueled classroom discussion about the experiences of students of color in the school system.

“We started talking about dropouts,” Rodriguez says. “We looked at the history of inequality in education in the United States; that evolved into why there was such a high poverty rate. That provided a foundation for discussion about the intersection of inequality in education and teacher quality and the distribution of high quality teachers in minority urban high schools.

“Teacher quality was one area the entire class really wanted to tackle,” he says.

Tranette and her classmates had an ideal in mind.

“If a teacher comes into a classroom and we don’t talk, I put myself in a shell and I sit back,” she says. “Some students don’t even have the confidence to raise their hands. It’s the teacher’s job to keep students interacting with each other so they aren’t afraid to ask.”

Teachers may not know what life is really like for students such as her and her classmates, Tranette says. Many of Edison’s students are recent immigrants still learning English. Growing up in Miami’s Little Haiti neighborhood means growing up in the midst of poverty and violence. One of Tranette’s close friends was murdered late last fall.

“The student should feel that the teacher understands where we’re coming from,” Tranette says. “Communication is better when there is understanding.”

Tranette thinks the classroom should always be lively, particularly in urban schools.

“That can be one of the most difficult tasks for teachers,” said American History teacher Nikisha Valdez. It was in her class that Rodriguez worked with students to develop the lessons for teachers, and she nominated Tranette for the Princeton Prize.

“Tranette said that a quiet classroom isn’t necessarily a good classroom,” Valdez says. “A lot of noise taking place in a classroom – it shows that students are engaged.”

Tranette encourages the use of interactive games and activities. Teachers need to be up and moving, not making pronouncements from behind a desk.

“They need to be walking the aisles and sitting next to students,” Tranette says.

Opening Eyes

Rodriguez wanted preservice teachers to hear what the students at Miami Edison had to say. Rather than simply sharing the insights he heard in the class, Rodriguez decided to invite the students to Florida International University to talk to future teachers directly.

Soon Tranette and her fellow students Dashima West and Danielle Dorizar were working on a lesson for preservice teachers.

Their mere presence in a college classroom – as driven students from a “failing” school — was enough to open the eyes of some FIU students.

“When I came into that classroom, I was stereotyping: [Miami Edison] is dangerous,” said Anissa Ramos, one of the preservice teachers in Rodriguez’s course. “You would think there is no parental involvement. Why would I want to go out of my way to work at a low-income school?”

Then Ramos heard what the Miami Edison students had to say. She heard Tranette make a plea for “alive” classrooms, in which students engaged and talked. She saw video clips the students had brought — showing Miami Edison students actively debating controversial issues in class, rather than sitting quietly and absorbing a lecture.

“I definitely think the communication factor was really important,” Ramos said. “The typical stereotypes — that’s not at all what I found with these students. As far as how they communicated with us, they each got very personal and spoke very maturely about the situation. I would definitely work at a lower-income school.”

Tranette’s history teacher remembers a time when she, too, was nervous about Edison. Nikisha Valdez is a Latina, originally from Texas, and she was aware that schools serving students of color often are the subject of stereotypes. Even so, Valdez says she wasn’t entirely sure what she was getting into when she was assigned to teach at Edison.

“I had never met anybody who was Haitian before,” Valdez says.

Although Valdez is often greeted by gasps or knowing looks when she tells people where she works, she wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I have amazing relationships with students that will last for a lifetime,” Valdez says.

Tranette thinks so too. She says she wishes she could bring Valdez with her for her freshman year at the University of North Florida.

‘I Had A Voice’

Tranette says she opened up in Valdez’s class because of the way classes were structured.

“There was a class discussion. We listened to everybody,” she says. “That was one class where they actually cared about what we learned, how we learned, whether we understood or not. They cared how we felt about a situation. I learned that I had a voice.”

And what a voice it is.

“With other youth around the country, students like her, if they don’t participate, they’re seen as disengaged,” Rodriguez says. “They’re dismissed. Here’s a case where persistence and developing trust and patience paid off. Look what happened: She became a star.”

As a senior, Tranette took Advanced Placement classes, was a member of the National Honor Society, spent afternoons separating trash from glass and paper as part of the Eco Club, and ran for prom queen. Most days, she didn’t make it home until 8 p.m. because of all of her school-related pursuits.

But she says she got involved in some of her favorite school activities because of an important lesson she learned from Valdez and Rodriguez. The lesson: You can’t be afraid of rejection.

“They’ve seen a lot in me,” said Tranette, “It’s up to me to notice it too.

“I wish all teachers were like that.”