On July 25, 2016, when First Lady Michelle Obama addressed the Democratic National Convention, she pointed out the significance of hers being an African-American first family of a country with a long legacy of racial injustice, commenting, “I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves.”

Her words touched off a small-scale media debate about whether or not her assertion was true. News sources like Fox News, PolitiFact and The New York Times fact-checked her statement and confirmed that the federal government had indeed relied on the labor of enslaved people during the construction of the White House. Regardless, thousands of Americans took to social media expressing disbelief.

Obama’s speech—and the nation’s reaction to it—reflects a current and critical need that curators and educators at the Smithsonian Institution’s newest museum hope to meet on a broad scale: the need for a fuller, more robust understanding of freedom, justice, citizenship and history, informed by the voices and lived experiences of African Americans. The much-anticipated National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) is slated to open in Washington, D.C., September 24, 2016.

The Hundred Years Story

Although Congress passed the legislation that launched the NMAAHC in 2003, it could be argued that the museum has been in the making for the last 100 years.

“During the 50th anniversary of the Civil War in 1915, an African-American veterans organization was allowed to participate in the triumphant parade down Pennsylvania Avenue,” explains Esther Washington, NMAAHC’s director of education. “They had been excluded from the 1865 parade; their participation in 1915 was a sign of progress. It was this group that first envisioned a national memorial.” The group began fundraising and established themselves as the National Memorial Association. In 1919, Congress held hearings on legislation to authorize a building that would, in the words of the National Memorial Association, “depict the [N]egro’s contribution to America in the military service, in art, literature, invention, science, industry, etc.” But funding was derailed by the stock market crash of 1920.

Over the next 100 years, the idea for a memorial evolved into the call for a museum, a place where African-American lives, history and culture could be documented and shared with Washington, D.C.’s hundreds of thousands of yearly visitors from across the country and around the world. But the journey to September’s opening was plagued by “fits and starts” (as Washington describes it) that mirrored African Americans’ unsteady march toward equality and full citizenship. Proposals to launch the museum stalled in Congress. Planners and city officials went rounds over the location. Finally, in 2003, President George W. Bush signed an act of Congress establishing the NMAAHC as a Smithsonian institution. The five-acre museum site on the National Mall was selected in 2006.

The Importance of Space and Place

Opening a museum documenting the legacies of African-American life in Washington, D.C., is significant for many reasons.

Slavery was legal in the nation’s capital. Like most African Americans across the South, Black people living in D.C. during the Jim Crow era suffered segregation, disenfranchisement and brutality. Today, D.C. remains a very segregated city where many African-American neighborhoods have been disrupted by gentrification. And the fact that the demand for a national space to memorialize the lives of Black people wasn’t met for 100 years is, to many NMAAHC supporters, an indication that the United States still has a long way to go in the journey toward racial equality.

The location on the National Mall is also critical to the identity of the museum. The 1963 March on Washington and the 1995 Million Man March both took place on the Mall. The museum is within view of the White House and the Washington Monument and near memorials to Martin Luther King Jr., Abraham Lincoln and George Washington, all figures whose influences on African-American history are documented in the NMAAHC.

The Museum

The NMAAHC has a four-part mission: to provide an opportunity to explore African-American history and culture through interactive exhibitions; to help all Americans see how their stories, histories and cultures are shaped and informed by global influences; to explore what it means to be an American and share how values like resiliency, optimism and spirituality are reflected in African-American history and culture; and to serve as a place of collaboration that reaches beyond the nation’s capital.

September’s opening represents nearly a decade of searching for artifacts across a country whose history books have—as reactions to Obama’s speech revealed—largely erased, ignored or denied the lived experiences of Black Americans. The museum will display over 37,000 artifacts grouped into exhibits on civil rights, clothing and dress, education, religion and slavery, among other topics, organized into three themed galleries: history, community and culture. Curators spent years collaborating with institutions that were independently documenting African-American history by collecting rare surviving artifacts. Some of the most notable installations: a 19th-century slave cabin from South Carolina, a segregation-era railway car and the Parliament-Funkadelic Mothership.

“From birth to every age that follows,” Washington promises, “we are planning something for you.”

Looking at the Whole Learner

Like their curator colleagues, staff from the NMAAHC education department have been working for years in anticipation of the museum’s opening, piloting curricula with the goal of making them available to educators nationwide. Their primary focus? Telling stories of agency and resiliency through the African-American lens. “We want students to be more comfortable having conversations about identity than generations have been previously,” says Candra Flanagan, coordinator of student and teacher initiatives.

To accomplish this goal, NMAAHC’s educational programming begins with early childhood and is rooted in positive identity development. Using art, literature and touchable objects, the early childhood facilitators drive home each child’s sense of self and role in a community while also enhancing their literacy skills.

“It’s all inquiry based, and it’s focused on how each person is unique,” Washington says, adding that children as young as 6 months old notice racial differences. “The research shows that if you can work with children on those areas as they are in their formative stages, they grow up much more open-minded and accepting of others.”

In the program Everyone Makes a Difference, little ones from pre-K through early elementary explore what people do to make a difference in their neighborhoods, homes and schools. Through art, literature and objects, they talk about people in history who have helped to effect change. A facilitator might, for example, use a gavel to discuss how African-American activists and attorneys have employed the courts to make the United States more racially just. Washington also gives an example of the role art plays in the curriculum: “We’ll talk about a story that an artist is telling, and it might be a piece that specifically focuses on justice or civil rights.” Children create self-portraits illustrating how they can make a difference.

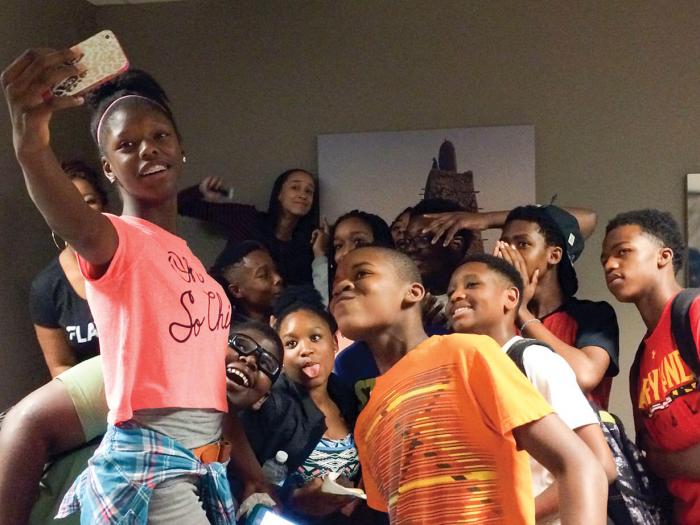

Ashley Bessicks, a high school English teacher in D.C. Public Schools, has taught one of the most successful workshops developed by the museum: a five-day teen literature and writing workshop called Power of the Written Word. According to Bessicks, students engage in “intensive study of African-American literature, while honing skills in writing (like writing complex sentences, finding our own voices in writing, drafting narratives).” When Bessicks plans a workshop—which she’s taught for several summers—her objective is for the students “to share a learning experience—about literature, about writing, and open an authentic dialogue about self-identity, African-American culture, and explore our history.”

Each year, Power of the Written Word closes with a celebration that involves students and their families and allows students to share pieces they’d composed during the workshop. For Kelly Sidner, currently a high school senior, the summer 2015 workshop made her see herself as a poet.

“We had to write about invisible societies and invisible people in society, and I wrote about single Black mothers because that’s who I was raised by,” Kelly reflects. “When I wrote about it, it opened me up to my more poetic side, and I realized how I really enjoy writing poetry—and that’s also one of my most famous poems.” She’s performed the piece a number of times, and received her first-ever standing ovation.

Supporting Educators

While the museum will have tons to offer people of all ages and walks of life, its programs will also cater to educators. One of their programs for educators centers on difficult subjects like slavery, race and racism. Let’s Talk!: Teaching Race in the Classroom is a week-long workshop in which teachers grapple with these topics—including their own personal journeys with them—and then gain techniques for teaching about them. “When we are working with educators, we seek to give them very age-appropriate language,” says Flanagan. “We work with educators and say, ‘Let’s start by talking about where your students are. Let’s think about where they’ve been and where they’re going developmentally. Then, let’s see how we can support you to teach about issues around race and identity from a place of strength.’”

Education is at the heart of this museum, from the interpretation of the exhibits to the downloadable print materials describing the artifacts to the in-person and online programming. “One of the first things we embraced was the role that education has always played in the African-American community and bettering people’s lives,” Washington observes, noting that it was once illegal for African Americans to be formally educated, but that Black people throughout U.S. history have literally risked their lives to seek knowledge and preserve their heritage. NMAAHC staff honor that legacy and the work of educators. “We appreciate, applaud, respect, are in awe of the work that classroom educators do every day,” Flanagan emphasizes, “and we want to be here to support them.”

Not in D.C.? You Can Still Engage With the NMAAHC

Right now, you can explore over 7,000 of the artifacts featured in the NMAAHC with your students via the museum’s website.

To expand the experience, search for “African American” at the Smithsonian Learning Lab for over 17,000 results that can be filtered, downloaded, shared and “favorited.” Select the “Learning Lab Collections” tab to explore specific images and objects in depth. You’ll find learning materials provided by the Smithsonian’s education staff, including lesson plans and ideas, activities and discussion questions. Each Learning Lab Collection is also labeled by subject (e.g., civics, U.S. history, writing and literature) and age level.

Over the next few years, resources for all NMAAHC collections—and the programs described in this article—will be available at nmaahc.si.edu. Materials for Let’s Talk! Teaching Race in the Classroom will be online by the end of 2016.

You can also celebrate the September 24, 2016, opening of the NMAAHC at your school through the “Life Every Voice” campaign. Host an event, and tell the museum—and communities around the country—how you and your students are celebrating African-American history and culture. Register here.