When the Teaching Tolerance Educator Grants program launched in 2017, we wanted to support educators in embedding anti-bias principles throughout their schools, creating affirming school climates and educating youth to thrive in a diverse democracy.

An important aspect of this work is meaningfully addressing the ways in which racial injustice grounds American history and our present.

This year, two educators who received Teaching Tolerance Educator Grants braved the topics of white supremacy and racial injustice in their classrooms and tied the roots of those topics to the lived experiences of people of color today.

While one class thought creatively about Confederate monuments in their city, the other explored racism and privilege in a thematically designed curriculum. Both projects modeled the power of student voices to shift the narrative about race in the United States, and to enact change in their communities with curiosity, solidarity and strength.

New Orleans, Louisiana

When New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu ordered the removal of four Confederate monuments from his city in 2015, he announced a public process to determine their replacement. Amy Dickerson, a third-grade teacher at Homer A. Plessy Community School, wanted to give her students a voice in the decision. Two-thirds of Homer A. Plessy students identify as people of color; 57 percent are African American. Dickerson intended for her students to write persuasive essays on how to reimagine the public space of Lee Circle, where a statue of Robert E. Lee had been removed.

But first she needed to provide historical context. Louisiana state standards offered scarce guidance, with no mention of slavery until fifth grade. She decided to traverse the terrain on her own, being careful not to shelter her students from the truth while presenting the information in an age-appropriate manner.

“It was interesting for me to navigate through the material because they are third-graders and haven’t been exposed to that history yet,” she recalls. “So we talked about how slavery began, what people thought about it, how and why the Civil War began, and important figures in the civil rights movement. I tried to tie it all together in a way that made sense to them.”

Dickerson did not dwell on the controversy about Confederate monuments, as the statues had already been taken down. She instead focused on the question of what should replace them. This tactic, she says, helped build community investment.

Christina Kiel, mother of one of Dickerson’s students, initially hesitated at the thought of discussing the topic at an early age. “When I first heard about it, I was excited,” she says, “but I was also really nervous. I thought, ‘How do you talk to third-graders about Confederate monuments without indoctrinating them into your political views?’” Overall, however, Kiel supported the project. “There’s really no way of making this pretty,” she recollects. “You have to learn about it.”

After visiting the sites where the monuments once stood, Dickerson led her students in an open inquiry about their symbolism. “This man was a general in the Confederacy,” Dickerson told her students. “[H]ow does it make you feel to know people didn’t want that taken down? That they wanted to continue to celebrate that person?”

Students explored the complexities underlying the simplistic narrative of good and evil and concluded that no history is black and white. Instead, they determined that the past transpires in shades of gray. “[Confederate leaders] might have done good things in other ways,” Dickerson’s students speculated. Eventually the class decided that, while the men honored by Confederate monuments may not have been wholly bad people, the monuments themselves represented exclusionary ideals.

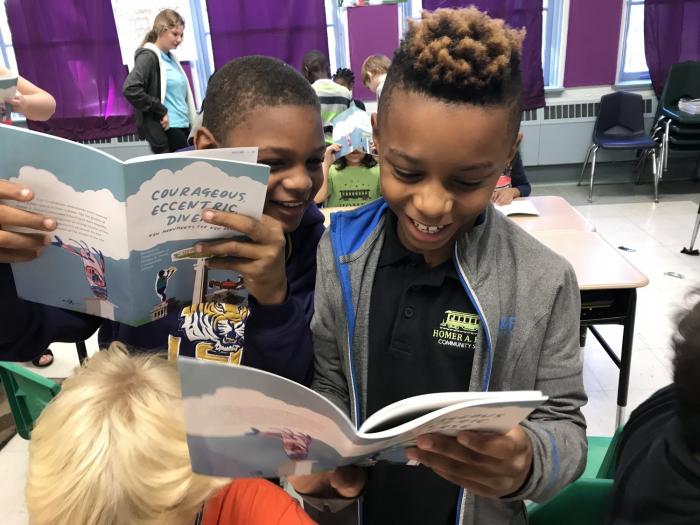

Students then considered how to inclusively represent New Orleans’ identity. They worked with 826 New Orleans, a national network of nonprofit youth writing and publishing centers. Tutors from 826 conferenced with students about their ideas, research and writing. Students illustrated their proposed monuments, mounting their drawings on photographs of the empty spaces where the Confederate monuments once stood. The class’ selections ranged from alligators, beignets and crawfish to artists, civil rights activists and Solomon Northup, a free black man who famously wrote about being abducted into slavery. Students published their work in a book they titled Courageous Eccentric Diverse: New Monuments for New Orleans.

Upon the book’s publication, students read their pieces at a community brainstorming session for selecting new public monuments. One student wrote about local artist George Rodrigue and presented the book to Rodrigue’s widow, Wendy, when he spotted her in attendance. “She looked at it, started reading it, and she just started crying,” remembers Dickerson. “The student saw his impact. He saw that his words have power and meaning.”

Educators can use their Teaching Tolerance Grants to fund projects for their classrooms, to start initiatives in their schools and to embed anti-bias programs throughout their school districts. Awards range from $500 to $10,000 and help students develop strong identities, honor diversity and think critically about injustice.

Grants are awarded on a rolling basis. Visit the grants page for more information.

Floyd, Virginia

Jenny Finn lives in Floyd, Virginia, a one-stoplight rural Appalachian town with 425 residents. After moving to the area several years ago, she heard about black residents feeling unwelcome. When numerous Confederate monuments were being taken down in the region, for instance, the town circulated a petition to keep their Confederate monument outside the courthouse.Finn says when high school students flew Confederate flags from their trucks parked in front of school, no one commented.

Finn explains that overt racism has occurred in Floyd, like when a white teenager shouted, “White power!” at an African-American student on school grounds. Yet more common, she says, are the subtle racial tensions, which are as persistent as they are insidious. “It’s shoved down underneath,” she says. “Kind of like the rest of our country.”

To start a discussion about race in her community, she created a course called Courageous Conversations: A Course on Race, Racism and White Privilege and the Role of Creativity in Transformation. She implemented the curriculum at Springhouse Community School, where she is the head of school and a teacher. The 99 percent white micro-school (a modern equivalent of a one-room schoolhouse) serves students in grades 7–12.

Finn strove to cultivate a culture of discomfort from the outset. “If you want to be comfortable, things will continue in the way that they have,” she told her students. “To be a citizen of this country who cares about everyone in it, you’re going to have to take on some discomfort.”

Finn’s students completed the “Difficult Conversations” self-assessment in the Teaching Tolerance guide Let’s Talk! to initiate reflection. They composed a list of their vulnerabilities when it came to talking about race, such as, “I’m overwhelmed by the complexity,” “I don’t have it all figured out” and “I’m scared I might be racist.”

Next, the class dove into a firsthand history lesson about white supremacy. With the help of the TT grant, they traveled to Charleston, South Carolina, where they visited the Slave Dwelling Project—a program that brings together historians, writers, educators and legislators to document and preserve dwellings of enslaved people. Students spent the night in restored slave quarters on the Magnolia Plantation and learned about the dwellings’ history from the project’s founder, Joe McGill. Rather than engaging students in a simulation, the project focused on remembering the past and preserving these spaces.

The class met with a historical scholar at the Old Slave Mart Museum, a site where enslaved people had once been sold. They also met with Cleveland Sellers, a survivor of the 1968 Orangeburg Massacre—an act of police violence against segregation protesters. Students completed research projects related to a site they had visited in Charleston.

With historical grounding in place, the class turned its attention to allyship. Finn emphasized the importance of listening and standing beside—not in front of—those experiencing the effects of racism and white supremacy. “Can we as white people develop the skills to listen to people of color? To those who are having a different experience in this country?” she asked her students. She led students in lessons about the pitfalls of colorblindness and “reverse racism,” exploring people’s tendency to evoke these notions to avoid honest discussions about race and racism.

The semester culminated with a series of conversations hosted at the predominantly African-American Mt. Zion Christian Church in Floyd. Congregation members spoke about being black in Floyd County and about the town’s potential to overcome its racial divide. One couple retold their experience as the first black members of the town’s rescue squad. When students asked if they had encountered racism while entering people’s homes, they replied, “Honestly, there were a couple of times when we were coming into somebody’s house, and you’ve got people who are hurting and they’re asking if there’s anybody white they can call.”

“It gave the students pause,” recollects Kevin McNeil, the church’s pastor. “For them it was like, ‘Wait a minute.’ You hear about things, you see them in movies, but to have somebody sitting there in front of you—that makes it very real. It makes it live in your moment.”

The conversation series ended with a community potluck. “We had fellowship together,” remembers McNeil. “We experienced a very spiritual moment where people who would not normally be found together were singing together, laughing together.”

Finn’s curriculum exemplifies her profound investment in mutual partnership. “Her commitment to the exposure of truth is remarkable,” recalls project collaborator Shana Tucker. “It’s infectious. Her integrity is transparent. She brings all of that in when she asks, ‘Will you participate in this with me?’ That makes it very easy to say yes.”

Ehrenhalt is the school-based programming and grants manager for Teaching Tolerance.

TT Grants in Action!

Massachusetts educators organized a conference focused on self-love, empowerment, self-advocacy and sisterhood for black and brown girls.

The Social Construction of Normalcy

In Charleston, South Carolina, third-graders and their families read children’s books with diverse characters and wrote to each other about what was being perceived as “normal” in the stories.

Housing Injustice in NYC

High schoolers worked with professional photographers and journalists to investigate local housing injustice, then presented their findings at a public symposium.

Humans at the Border

Student activists created a photojournalism project to investigate the collision of politics and culture at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Art for Dreamers

In Chicago, high school students created art to affirm immigrant, refugee and undocumented students; sold their work; and donated the proceeds to a scholarship fund for undocumented students.

A special education teacher in Arizona adapted her school’s playground to be wheelchair-accessible so that all students could enjoy it.

Read more about these TT-funded projects.