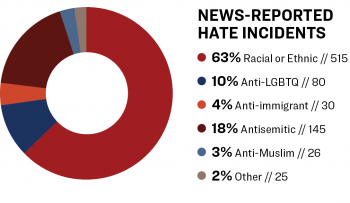

No one knows the extent of the problem nationally. In 2018, the SPLC’s Learning for Justice project, then Teaching Tolerance, collected hundreds of news reports detailing hate in schools directed toward individuals or groups on the basis of their perceived race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender expression, gender identity, immigration status, religion and more.1

We counted 821 verified hate and bias incidents spanning every state and Washington, D.C. We define “hate and bias incidents” to include actions—verbal, written or physical—that target someone on the basis of identity or group membership. They include slurs, hate symbols, graffiti and harassment.

Most of the incidents that made the news (63 percent) were racist. They included racial slurs, primarily the n-word, along with a dozen accounts involving blackface and a handful involving nooses. Antisemitism accounted for 18 percent of the incidents. They often involved swastikas or invoked Nazis or the Holocaust. These incidents tended to happen outside of the classroom in more public spaces, such as the outside of the building or at a sporting event. In the case of swastikas, it was not uncommon for them to be found in bathrooms. Social media often played a role in making these incidents public.

Many of the incidents drew outrage because they were perpetrated by adults, including coaches, school bus drivers, school board members and teachers.

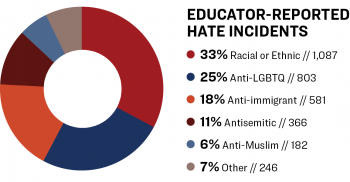

We know, however, that only a fraction of the incidents that occur in schools ever makes the news. To get a clearer view of the bigotry that students are facing every day, we reached out to educators in elementary, middle and high schools.2 More than 2,700 responded to our request, and they reported witnessing 3,265 hate and bias incidents in the fall of 2018 alone—an average of 1.2 percent incidents per respondent.

As with incidents reported in the media, race was the most common. Anti-LGBTQ harassment was not far behind. Many educators reported that anti-gay and anti-transgender slurs were extremely common and difficult to stop. Because educators were asked to describe incidents they had seen, the incidents they reported were more likely to have happened in class or in the school building.

Our data, though based on an unscientific survey, raises important questions: If 2,776 educators—from every U.S. state and Washington, D.C.—have witnessed this many instances of hate and bias in a single school semester, just how commonplace are these incidents? And what are schools doing about them?

This report fleshes out and describes the problem. It uses data from both the teacher questionnaire and news reports. The teacher reports confirmed our suspicions: There are far more hate and bias incidents than make the news. And school leaders vary considerably in how they respond.

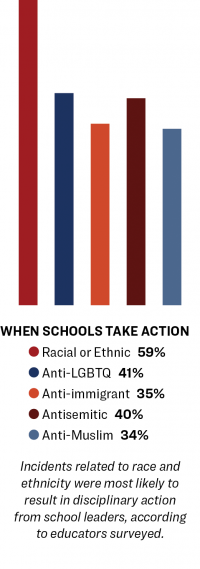

School leaders are responsible for nurturing and maintaining a healthy school climate. Best practices in countering hate and bias call for a range of actions to investigate, communicate, repair harm and restore the social fabric of the school. We asked educators about the actions their school leaders took to address incidents on their campuses: communicating with families; issuing public statements; providing professional development for school staff; investigating beyond the one act; supporting marginalized students; organizing pro-social activities; disciplining the offenders; denouncing the act; and reaffirming school values. The most common response was discipline, and even then, the vast majority of incidents resulted in no discipline at all.

To be clear, not every school is affected. About one-third of the teachers responding to our questionnaire witnessed no incidents in the first four months of the current school year. Many cited a positive school climate and lauded school leaders who work every day to create welcoming environments where hate and bias cannot thrive.

Negative Trends in School Climate

In 2016, Learning for Justice, then Teaching Tolerance, brought public attention to the school climate crisis in two reports, The Trump Effect and After Election Day: The Trump Effect. Based on surveys of thousands of educators during the campaign and immediately after the election, the reports revealed a wave of political and identity-based harassment in schools, where students across the nation were emboldened to bully and target classmates.

Educators detailed heightened anxiety among students from immigrant families and an uptick in verbal harassment and derogatory language based on race, religion and ethnicity. Ninety percent of the educators said that the campaign and election had negatively affected the climate at their schools. More than half of elementary teachers and one-third of high school teachers were reluctant to teach about the election or current issues because of the climate. Most believed the negative climate would be long-lasting.3

Evidence Is Mounting That They Were Right:

- In 2017, the Institute for Democracy, Education, and Access at the University of California at Los Angeles surveyed high school teachers. Educators reported that their schools had become hostile environments for racial and religious minorities and that white students especially had become more polarized and combative in class.4

- The FBI’s 2017 hate crime data—widely acknowledged as underreported—showed that hate crimes in K–12 schools and colleges increased by about 25 percent over 2016, considerably outpacing the national increase of 17 percent.5

- In 2018, Education Week partnered with ProPublica to analyze school-based hate incidents from 2015 to 2017. They found 472 incidents. Most, they reported, “targeted black and Latino students, as well as those who are Jewish or Muslim.”6

- In January 2019, scholars from the University of Virginia and the University of Missouri published a study in the peer-reviewed Educational Researcher comparing Virginia school climate survey results with 2016 election results and found an increase in middle school bullying in districts “favoring the Republican candidate.”7

How Bias at School Affects Students

We’ve long known that discrimination has measurable, adverse effects on the health of those who are targeted. Researchers first connected racism to hypertension in African-American subjects in the 1990s.8 And there’s no shortage of studies on the effects of discrimination on young people’s health in the years since. We know that when students are targeted for their sexual orientation, gender identity, immigration status, race, ethnicity, or other identities, their mental and physical health suffer.9 These students are more likely to report symptoms of stress, depression, ADHD, risk-taking activities, school avoidance and more.10 Recent research suggests that racial-ethnic discrimination can cause behavioral problems for children as young as seven.11

These effects vary based on whether the bias comes from school personnel, peers or others.12 Students bullied by peers deal with both physical and emotional fallout that can follow them throughout their lives.13 Studies show the damage is compounded when the bullying is based on one of their identities.14 And when students are targeted for more than one of their identities (e.g., race and disability), they are even more likely to report negative effects.15

Discrimination and biases from educators also have long-lasting effects. “Children who experience discrimination from their teachers are more likely to have negative attitudes about school and lower academic motivation and performance and are at increased risk of dropping out of high school,” reports the Migration Policy Institute. “In fact, experiences of teacher discrimination shape children’s attitudes about their academic abilities above and beyond their past academic performance. Even when controlling for their actual performance, children who experience discrimination from teachers feel worse about their academic abilities and are less likely to feel they belong at school, when compared to students who do not experience discrimination.”16

But the harm of a toxic school culture, where students are singled out for hate and bias based on their identity, isn’t limited to students who are targeted. The authors of a 2018 study published in JAMA Pediatrics surveyed just over 2,500 Los Angeles students and asked them to report their concerns about “increasing hostility and discrimination of people because of their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation/identity, immigrant status, religion or disability status in society.” They found that the more concern or stress students reported feeling, the more likely they were to also report symptoms of depression and ADHD, along with drug, tobacco or alcohol use. Unfortunately, it appears student anxiety may be rising: In 2016, about 30 percent of surveyed students reported feeling “very or extremely worried” about hate and bias. By 2017, that figure had jumped to nearly 35 percent.17