Following record-breaking voter turnout in the 2020 election, several state legislatures passed laws to disenfranchise voters, especially in Black communities. These attempts at voter suppression work in concert with censorship policies targeting education to further undermine civics literacy and engagement in the United States. It is no surprise that these attacks on voting rights and education followed the rise of the two largest civil rights movements of the modern era: Black Lives Matter and the Women’s March. The fear of a diverse society—of young people in classrooms learning of today’s civil rights struggles and their power to effect change—drives this backlash, which employs methods of suppression drawn from our country’s history.

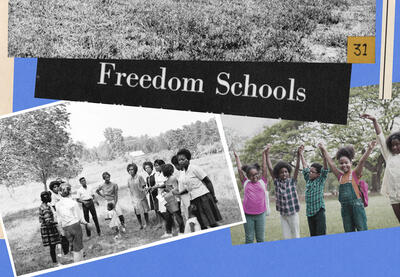

Discrimination is entwined into the foundation and systems of the United States, but so are models of people challenging oppression. In the current fight for justice, strategies from our history can help to develop our present leaders. Today, the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools model inspires and guides the work of both national programs, including the Children’s Defense Fund (CDF) Freedom Schools® program, and local community efforts, such as the Rosedale Freedom Project, part of the Freedom Project Network in Mississippi.

The History of Freedom Schools: The Right to Question

Mississippi stands out as the vanguard of voter disenfranchisement—both past and present. The state has led the effort to prevent Black people from voting ever since its 1817 constitution limited voting to white men who owned property. In 1960, 42% of Mississippi’s population was Black, yet in 1964 only 6.7% of Black Mississippians were registered to vote. In some majority-Black counties, not a single Black citizen had access to register.

Understanding the situation in Mississippi, Charlie Cobb, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) field secretary, proposed a school with the mission to fill the creative and academic void and to teach young people to articulate their own desires, demands and questions. Cobb envisioned students asking teachers questions that would challenge the myths of society and lead to new directions for action.

The fear of a diverse society—of young people in classrooms learning of today’s civil rights struggles and their power to effect change—drives this backlash, which employs methods of suppression drawn from our country’s history.

In 1964, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), SNCC and the NAACP operated as a united coalition called the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), and these organizations focused their efforts on increasing Black voter turnout in Mississippi. COFO developed Cobb’s vision of a school rooted in self-reflection and inquiry, incorporating these new “Freedom Schools” into the 1964 Freedom Summer, otherwise known as the Mississippi Summer Project.

According to COFO’s Freedom School data, 41 Freedom Schools operated in 20 communities across Mississippi in July of 1964, enrolling 2,135 students. Church basements and back porches became sanctuaries of learning for a disenfranchised population. Approximately 175 full-time teachers from all over the U.S. taught students with an average age of 15, ranging from small children who had not yet started school to elderly adults who

had spent their lives toiling in the fields.

The Freedom Curriculum: An Inquiry Learning Model

The 1964 Freedom School curriculum was a three-part exploration of academics (reading, writing and math), citizenship (case studies on education, economics and history), and recreation and the arts. Jane Stembridge, a graduate student at Union Theological Seminary in New York, was convinced by Ella Baker to work for SNCC and helped develop the first six units of the citizenship curriculum. In her 1964 memo “Notes on Teaching in Mississippi,” Stembridge wrote: “This is the situation: You will be teaching young people who have lived in Mississippi all their lives. That means that they have been deprived of decent education, from the first grade through high school. It means that they have been denied free expression and free thought. Most of all—it means that they have been denied the right to question. The purpose of the Freedom Schools is to help them begin to question.”

The purpose of part two of the citizenship curriculum for the 1964 Freedom Schools was to intentionally train students to become “agents in bringing about social change.” However, the curriculum was not designed “to impose a particular set of conclusions;” the goal was “to encourage the asking of questions, and hope that society can be improved.”

Educators used an assortment of questions to help students “look around” to understand their realities and develop an “awareness that there are alternatives.” Some questioning was designed to explore why students were attending Freedom Schools and to consider the difference between

the conditions of “Negro schools” and “white schools.” The students looked at pictures of resources available in non-Black schools and were asked, “What do you see in the pictures that is different from you and your school? Why do these differences exist?”

The segregation that facilitated those differences has persisted. A report by the Century Foundation found that in 2020 nearly half of Mississippi’s school districts were subject to a desegregation order or voluntary agreement with a federal or state court or agency for failure to adequately address segregation. The legacy and the current practices of segregation continue to harm Black students and communities in Mississippi and across the U.S.

The Next Generation of Freedom Schools

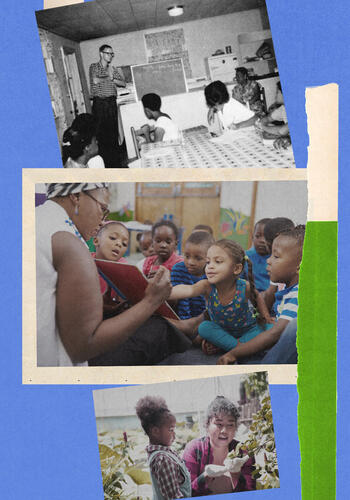

The Children’s Defense Fund (CDF) Freedom Schools® operate with the same spirit as the 1964 schools. “We’re very much mimicking that … same kind of resistance training,” said Kristal Moore Clemons, Ph.D., the national director of the program. “Anything we feel will better support children and families, that’s what you’re going to get on the ground.”

Civil rights leader Marian Wright Edelman founded the CDF in 1973 with the mission “to ensure every child a healthy start, a head start, a fair start, a safe start and a moral start in life and successful passage to adulthood with the help of caring families and communities.” The CDF Freedom Schools® program operates in 15 states and the District of Columbia, implementing a model similar to Charlie Cobb’s original vision with five components: “high quality academic and character-building enrichment; parent and family involvement; civic engagement and social action; intergenerational servant leadership development; and nutrition, health and mental health.”

Recognizing that thriving parents and communities are essential to children’s development, the six-week CDF Freedom Schools® program includes six parent meetings about financial literacy, health and wellness, and voter registration. The program also has students participate in a National Day of Social Action. During the 2022 summer program, students learned how to influence community perception by holding a rally focused on food justice, drawing attention to disparities in access to food and the ability to make healthy food choices.

Clemons recounted her experience one year when the National Day of Social Action theme was children’s health care. After students learned that more than 3 million children in the U.S. did not have health care, they organized a silent protest. “Strangers were coming up to us [asking], ‘What are you doing?’” Clemons said. “And one of the kids says, ‘We’re in a silent protest because the number of children who are not insured in this country is on my back. And that needs to change.’”

CDF’s social justice instruction and intensive reading and language curriculum bolster student learning. According to a 2021 assessment of CDF’s model, 70% of students maintained or improved their instructional reading level, avoiding the common setback of summer learning loss. The 2021 survey also showed that 92% of students agreed or strongly agreed that the program helped them prepare for school.

“What we do in the contemporary Freedom Schools context is similar to instilling [the] capacity to make a demand,” Clemons said. Making a demand is premised on the ability to know what one needs, which requires the skill of intentionally asking questions. Indeed, one of the cornerstones of the 1964 Freedom Curriculum was “education’s most powerful tool: the question.”

“If you look back at some of the old lesson plans from ’64 in the Freedom School, they taught about Black history, they taught about the art, they taught about movement building,” Clemons said. “And that’s exactly what our integrated reading curriculum is doing right now.”

Freedom Projects in Mississippi

Building on the historic 1964 Freedom Schools model, the Rosedale Freedom Project (RFP) has the stated mission to “[support] the Mississippi Delta’s young leaders in the development of critical consciousness and the practice of justice through community building, exploration, artistic creation, organizing, and the study of social history and grassroots democracy.” Founded by parents, students and educators, the RFP oversees a variety of academic and social justice programs, including community organizing for voting rights.

Jeremiah Smith, co-founder and director of programming for the RFP, explained the contemporary challenges of registering to vote in Mississippi. Voter registration in the state requires voter ID, which requires a visit to a Department of Public Safety (DPS) office—Mississippi’s version of the Department of Motor Vehicles—which might require, in such a rural state, a journey of many miles. Once, Smith brought a group of students in search of ID from Rosedale to the nearest DPS office, about 20 miles away in Cleveland. When they arrived, a sign on the doors said they needed to go to the DPS in Indianola, another 35 miles from Cleveland.

“We drive to Indianola, and we get there, and there’s a sign on that door that says you have to go to Greenville,” Smith said. Greenville is about a 30-mile drive from Indianola. “We get to Greenville, and they inform us that we need the student’s birth certificate. We can’t have a copy. We need his original birth certificate.” By the time the group returned to Rosedale, without ID, they had driven more than 100 miles in a circle around the Mississippi Delta.

To stay true to the mission of the RFP, Smith has worked in partnership with Mississippi Votes, an organization whose mission is to “empower young people, encourage civic engagement, and educate communities on voting rights through place-based grassroots organizing.”

“They were really trying to think about not only how we register people to vote,” Smith said, “but also how … do we sort of get at what the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was trying to do in the sense of building movements for more radical political positions [from] elected officials.”

The curriculum of the 1964 Freedom Schools and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party are conceptually linked. In 1964, COFO founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to “aid local citizens in setting up a Democratic Party structure to challenge” the prevailing exclusion of Black Mississippians from politics. In keeping with that spirit, Smith and Mississippi Votes helped students organize a voter registration project in 2019.

“At the time, we were having a district supervisor race,” Smith said. “We did door-to-door voter registration, we went out to a bunch of different public events, we met with the candidates and interviewed the candidates about what they wanted and what their positions were.” Smith’s students communicated with U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson, who was a former Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party organizer. “That’s really the work,” Smith said. “We want children who say to themselves, ‘I don’t have to be 20 years old or 30 years old to participate in making a difference in my community.’”

Education as Mirror and Window

Education and voting rights are inextricably linked, a connection embodied by Marian Wright Edelman, the founder and president emerita of the Children’s Defense Fund. In 1965, Edelman became the first Black woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar Association, and she led the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

“Ms. Edelman, she always said, ‘You can’t be what you can’t see,’” Kristal Moore Clemons said. “We look at providing curriculum for children so that they can see themselves in the curriculum and begin to reimagine who they are in the world.”

Related Articles From Learning for Justice

- No School Like Freedom School

By Lisa Ann Williamson - The End of Freedom School

By Sara Bullard