“With driver cards, illegal immigrants will take Oregon jobs.”—Op Ed, Oregonlive.com, January 2014

“Local protestors fast and pray for immigration reform.”—CW39 News, KIAH-TV, Houston, Texas, February 2014

“Illegal immigrants deserve deportation.”—Letter, The Baltimore Sun, February 2014

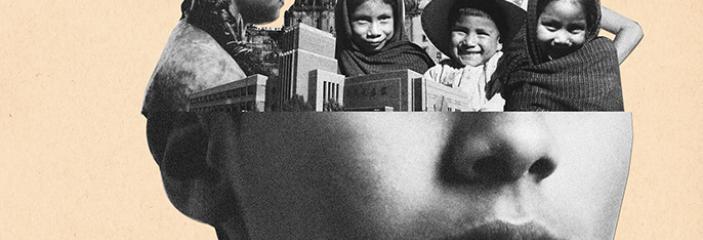

For at least a decade, headlines like these have shaped the way students and their families think about immigration. They have opinions; many have first-person experience. That range of opinion and experience makes teaching about current immigration policy a daunting task, one that some teachers choose to avoid.

Everyone—across the political spectrum—agrees that our current immigration system is broken. Although it’s by no means certain that Congress will pass comprehensive immigration reform this year, the issues are too important not to discuss in class. And, the issues are perennial. We face many of the same questions policymakers have faced since the 1790s.

Immigration policy concerns us all, and students deserve to be part of the debate surrounding it. If anything, the fact that the topic is controversial makes it even more urgent that we help students untangle emotions from facts and see how complex policy can emerge from the democratic process.

Facilitating those discussions is easier with some background knowledge about the legacy of immigration in the United States and the current state of U.S. immigration policy.

Who’s Invited?

It’s a question barely asked for the first 85 years of the country’s history. Even as the states voted to ratify the Constitution, the doors to immigrants—at least to Western European immigrants—were wide open. The nation needed settlers to fill up the newly-organized territories that extended to the Mississippi and, except for some worries about immigrants entangling the country in foreign intrigue, most immigrants were welcomed without question and with little red tape.

The process of immigration was virtually unregulated. There was no national office to oversee the admission of immigrants. If a person could afford to pay for passage, he was almost guaranteed entry into the United States. Only those with terrible diseases (such as yellow fever or smallpox) were kept out, and they were simply quarantined until they were no longer contagious.

In the mid-1840s, when the first great wave of poverty-stricken Irish immigrants arrived, new factories and a growing web of railroads absorbed the unskilled labor. Even though Irish labor was welcome, the Irish themselves weren’t—groups like the nativist Know-Nothing Party saw these immigrants’ Catholicism, poverty and lack of education as a cultural threat.

The need for labor, coupled with a seemingly endless expanse of open country, kept immigration wide open until the 1880s. That decade brought the first restriction in the form of the Chinese Exclusion Act, passed only after the West Coast railroads were built and the low-cost labor the Chinese supplied was no longer needed. This decade also ushered in federal control, most notably in the establishment of immigrant intake stations, such as Ellis Island.

Racial and ethnic fears, as well as a decreasing need for foreign labor, shaped a rising tide of anxiety about immigrants over the next 40 years as new groups—this time from Eastern and Southern Europe—arrived. Like the Irish, these new immigrants were often poor and uneducated. Unlike the Irish, they arrived speaking no English; many of them were Jews.

By the 1920s, the assembly line and increasing automation meant that business no longer needed an endless supply of unskilled labor. The gates could close, and close they did with the passage of the National Origins Act, a law that set quotas for entry based on ethnicity. Congress made it clear: British, German, Scandinavian and Irish immigrants were fine, but everyone else was more or less undesirable.

The Act set up a “line” to get in; it set quotas and, for the first time, required immigrants to obtain visas before leaving their country of origin. With the arrival of the Great Depression, the doors closed even tighter; many Jews trying to escape from Germany and Eastern Europe were denied access because of the quota system. With the beginning of the Cold War in the 1950s, the United States opened the doors a crack for refugees from Communism, but people from Africa, Asia and most of Latin America were still out of luck.

In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson threw out the racist quota system when he signed sweeping immigration reform. Sitting at the feet of the Statue of Liberty, Johnson said that U.S. immigration policy “has been twisted and has been distorted by the harsh injustice of the national origins quota system.” The old law, he added, was “un-American,” and he promised “that it will never again shadow the gate … with the twin barriers of prejudice and privilege.”

The new law dramatically changed whom the United States welcomed. It opened, for the first time, large-scale immigration from the Americas. Numerical limits still applied, but this law gave preference based on skills and residential status of family rather than nationality.

More recently, reforms in the 1980s and 1990s tinkered with these numerical limits and introduced greater border security (nonexistent for most of U.S. history). The system of limits and preferences meant that, for some people, there was no way to enter the country, so the laws also attempted to deal with the problem of illegal immigration.

Warm Welcome or Cold Shoulder

The country’s gates may have been open wide during much of the 19th century, but American arms were not. As early as the 1750s, Benjamin Franklin famously complained about the Germans settling in Pennsylvania. “Not being used to liberty,” he grumbled, “they know not how to make a modest use of it.” He worried that they were clannish and refused to learn English.

That complaint would be echoed in one form or another, against different targets, for the next 250 years. In the 1790s, Americans feared French immigrants would bring revolution; in the 1840s, some claimed the Irish were a separate race that took away American jobs; and, in the 1890s, Jews from Eastern Europe were accused of being too different and bringing anarchist thinking. The Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s was as much anti-immigrant as it was anti-black, and early 21st-century rhetoric about Mexican immigrants follows this old pattern.

Can I See Your Papers?

Before the 1880s, there were no illegal immigrants, because there were no limits on immigration. With restrictions—of Chinese, then Japanese, then the quota systems—came illegal immigration, and deportation.

It wasn’t until the 1940s, though, that noncitizens needed “paperwork” to live in the United States. As war began in Europe, Congress passed the Alien Registration Act, which established for the first time two categories of noncitizens: legal residents and those who weren’t. It was the beginning of what we now call the green card.

Today, we’ve multiplied those categories, complicating the paperwork. People who have permanent residency status (the green card) may become citizens if they want. Others, however, only have permission to be in the country for the time being. Their visas spell out the conditions under which they are here: as students, visitors or guest workers.

The Bracero program, created in 1942 as a wartime measure, ushered the first guest workers (mainly Mexican) into the country to harvest crops. That program ended after two decades, but not before being replaced by another guest-worker program that was also mainly for agricultural workers. Under immigration reform passed in 1986, the guest-worker program grew larger. Today, many guest workers toil in agriculture, but even highly-educated immigrants, such as teachers, can become trapped with no path to permanent residency or citizenship.

Guest workers have no path to citizenship; their visas typically allow them to stay in the country only for a year. They are often tied to an employer who has paid to bring them here, and they are easily exploited. With temporary residency, guest workers have few legal protections or rights.

I Will Support and Defend

The history of naturalization—the process by which a person becomes a citizen—stands in stark contrast to that of immigration. While immigration started out wide open and gradually came under federal control and grew more restrictive, the rules for naturalization have been firmly under federal control from the beginning. Two hundred years ago, the process of becoming a citizen was relatively easy—but few people qualified.

The Naturalization Act of 1795 set up a path to citizenship, but only free white persons were eligible. For others, like Asians and free persons of color, there was no path. Their children were not citizens either. That didn’t improve with ratification of the 14th Amendment and birthright citizenship; it took 30 years of court cases for natural-born children of people of color to be guaranteed citizenship. Until passage of the 19th Amendment, a woman shared the citizenship status of her father or husband.

For a freeborn white man, the process was simple. He had to live in the country for five years, swear allegiance to the United States, renounce other loyalties and convince his local court that he believed in the principles of the Constitution, was of sound character and was a productive member of society. Virtually all of this could be done in a simple two-step process: Go to the county court to declare the intention to seek citizenship, and then appear before the judge again three years later to petition for it.

Today, eligibility is broader, but the process has become more difficult and expensive. Two requirements endure: a residency period and belief in American ideals and values as represented in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution. Under the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, the residency period grew to 14 years, but it was rolled back to five years in 1802. In the 1850s, the American Party (the Know-Nothings) fought unsuccessfully to have it lengthened to 21 years.

Since then, other requirements have been added. The ability to speak English was added in 1906. Today, you need to be a permanent resident (have a green card), take a civics and language test and appear in federal court. The application is complicated and many prospective citizens employ lawyers.

Today’s Debate

Students should know that the United States has a checkered history when it comes to immigration, residency and naturalization. Our need for immigrant labor has offset (but not neutralized) the fear of those who are different. At times, we’ve celebrated the great salad bowl, and, at other times, we’ve worried about assimilation and threats to our ways of life. Immigrants have been allowed in or turned away based on the needs of powerful economic interests, and those who are allowed in have often been met with xenophobic and nativist reactions.

It’s important for students to look at today’s immigration debate in light of past policy debates. How were previous policies made? How were economic, racist or other factors at play? What is different today, and, more importantly, what is the same?

Conversation Starters

Immigration reform is complex, but a few key issues pop up again and again in the media. These topics can be great for classroom conversation—if you ask the right questions.

DREAMers

Millions of undocumented youth who were brought to the country as children are unable to get jobs or gain admission to college. Republicans and Democrats agree it is time to provide them a path to legal residency—the question is how? What should DREAMers have to do to secure legal status?

Amnesty or Deportation

About 11 million unauthorized immigrants live and work in the United States today. Some say they should be deported, while others support a path to legal residency. What would deportation of 11 million people involve? What would be required to receive amnesty?

Path to Citizenship

For 250 years, the United States has recharged its spirit and economy by extending citizenship to immigrants. The question now is, once the undocumented gain legal status, will we extend the same opportunity to them? If not, how do we reconcile that decision with our ideal of equality?

Visa Eligibility

The current system’s quotas and preferences mean there is no way some people can ever enter the country. Guest-worker visas mean some will labor here with no representation, few legal protections and no chance to earn citizenship. How do we make rules that are fair, generous and in keeping with our values?

Enforcement

From border security to deportation and fines, we must decide how to enforce the law with employers and employees who are undocumented. What’s realistic, and what reflects our goals and values?