In February 2015, Matt Hennick, a teacher at the Hillcrest Youth Correctional Facility in Salem, Oregon, learned that one of his former students had committed suicide while being pursued by police.

“Those are the tough ones,” Hennick says of the sometimes-crushing realities of teaching in the juvenile justice system. “It’s happened more often than I care to remember. But we also have success stories. When I see a young man on the outside and he’s working, that’s a success story for me. I’m like, ‘OK, that one made it.’”

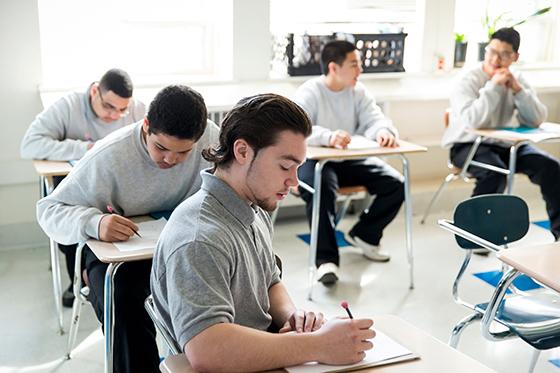

Hennick has a challenging job, as do all educators working in confined environments: juvenile detention facilities, residential treatment centers, group homes and mental health facilities, among others. All confined schools are not equal, but they share similar challenges—varying student ages, abilities and credit levels; many youth with special needs; difficulty accessing school records; varying (often short) lengths of stay; students who have experienced trauma; inadequate funding; and the daily disruptions associated with confinement.

Given these obstacles, it’s not surprising that—according to the Annie E. Casey Foundation—just 25 percent of juvenile offenders make a full year of academic progress per year of confinement; only 1 in 10 will earn a high school diploma. Outcomes for foster children are equally bleak: Seventy-five percent of students are below grade-level for their age and less than half will graduate high school by age 18.

The fact that confined youth aren’t receiving adequate education is both a legal problem and an equity issue.

“Legally, children who are held in county or state facilities are entitled to an equivalent education to what they would get outside,” says Mark Soler, executive director of the Center for Children’s Law and Policy. “That’s clear law.”

It’s a law that affects a significant number of young people. The federal government estimates there are 60,000 youth confined to 2,500 juvenile justice residential facilities in the United States every year. Other estimates are higher. But although current performance statistics reflect some grim realities, a collection of innovative educators around the country is actively working to raise the bar for teaching and learning on the inside. These programs are achieving outcomes that support student success after custody or care and are serving as models for educators in traditional settings.

Maya Angelou Academy

Emphasis: A Culture of Achievement

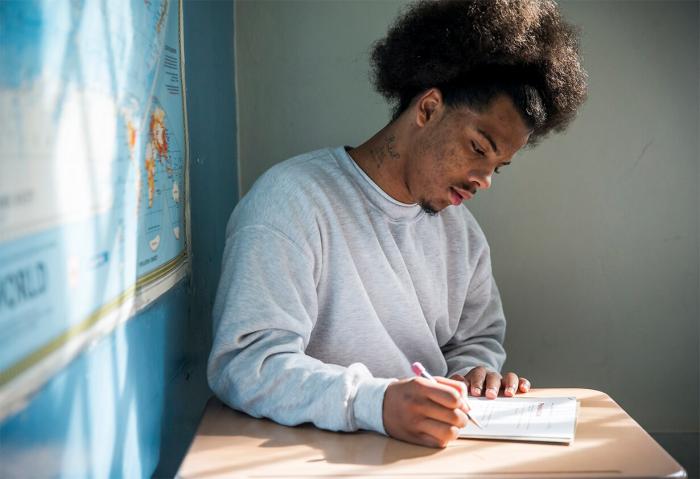

At Maya Angelou Academy in the New Beginnings Youth Development Center near Laurel, Maryland, students are called “scholars.”

Founded in 1997 by James Forman Jr. and David Domenici, the Academy replaced the District of Columbia’s notorious juvenile detention school, Oak Hill Academy.

The founders quickly covered the dour prison school with scholar art, plaques and certificates and turned the auditorium, once nailed shut, into a center for awards ceremonies and gatherings. The staff members use a modified version of a Positive Behavioral Incentive Program to instill values: safety, respect, responsibility, integrity, self-determination and empathy. Scholars receive awards and recognition for academic achievements and for demonstrating values.

“You want to change the cultural norms,” says Domenici, now executive director of the Washington D.C.-based Center for Educational Excellence in Alternative Settings. “Ultimately what you want is the culture to be dominated by achievement by kids who are trying hard.”

Domenici learned to be flexible with curriculum; for example, the short duration of scholars’ stays meant a semester system didn’t work. So the school restructured its curriculum into a series of eight, month-long units, allowing scholars to finish credits. To account for the wide variation in abilities, materials are customized with substitute vocabulary and paraphrasing, allowing all scholars to participate.

When executed by a dedicated and skilled teaching staff like the Academy has, the approach works: Academy scholars earn credits and achieve grade-level gains in math and reading at rates almost three times what they experienced before entering the facility.

“Sometimes there’s a need to convince youth of the importance of education first, before you can actually get into the work of doing it,” says longtime Academy teacher and Special Education Case Manager Quincy Roberts. “You’re overcoming a lot just to get to the point where you can get into completing some work.”

The Missouri Model

Emphasis: A Holistic Approach

Missouri’s juvenile justice system was once the stuff of teenage nightmares, but—after decades of reform—today’s Missouri Model is synonymous with small, residence-like facilities, individual care, partnerships and aftercare.

Education is an integral part of the Missouri Model’s success. Each student has an individual learning program (including special needs Individual Education Plans) integrated into a treatment plan.

“Within that plan, they have an academic goal, a treatment goal and a transition goal,” says Scott Smith, education coordinator for the Missouri Department of Social Services.

Continuity and relationships are key; teachers and front-line youth specialists (treatment staff certified as substitute teachers) work as a team in classrooms of 10–13 students, essentially providing two specialized instructors per class.

Gwen Deimeke was a Department of Youth Services (DYS) teacher for 12 years (she’s now the statewide special education supervisor). Having previously taught at a private Catholic school, Deimeke found she could give more individual attention working for DYS, particularly with special needs students.

“In my math classroom, you’d come in with 11 kids, and typically they’re all in a different place in a different book. So I’m teaching anywhere from basic math to college algebra. It kind of runs the gamut, but they each get individual lessons,” Deimeke says. “The special needs kids have to have a little more direct instruction time, but we’re able to do that.”

In Missouri, 77 percent of youth make academic progress while confined to residential treatment programs.

A service coordinator creates a post-confinement plan for school re-enrollment, employment, community service and extracurricular activities. Those coordinators stick with the kids during a four- to six-month aftercare period, often collaborating with an assigned college student mentor. The result? Missouri DYS reports that 89 percent of youth are “productively involved in school or work” at the time of discharge.

Oregon Youth Authority

Emphasis: Appropriate Use of Technology

Oregon Youth Authority (OYA) Education Administrator Frank Martin is hawkish on tech.

“One of the major goals is that the youth need to be digital citizens,” Martin says. “When they leave, they are going to be online.”

But allowing kids in juvenile justice facilities to roam the Internet freely is the equivalent of a digital jailbreak. Wasting time and engaging in online illegal activity are concerns, but the greatest concern is that a youth offender might contact a past victim. So Martin and OYA worked with Oregon’s attorney general to change rules to allow student access to an enclosed network and use email for educational purposes.

Now students known as the “OYA Geek Squad” refurbish computers that are then loaded with educational content. Offenders in Oregon can stay in youth facilities until age 25, so OYA campuses are drawing on the Massive Open Online Course movement and becoming College Level Examination Program centers.

Working with a grant from Study.com for digital content and textbooks, OYA also offers extensive online credit recovery and blended learning, a combination of brick-and-mortar instruction and digital learning.

Next, Martin plans to network OYA’s schools together using Google platforms and education applications. OYA is also implementing a closed-circuit wireless system that only broadcasts educational content from a contained server, allowing kids to take their studies back to their sleeping quarters.

“What I’ve learned is these kids are hungry for a keyboard. Even if it’s just education content, they’re good for it,” Martin says.

Is Confinement an Opportunity?

In a chapter he wrote for Justice for Kids: Keeping Kids Out of the Juvenile Justice System, Domenici of Maya Angelou Academy notes that many scholars say it’s the best school they’ve attended.

This may seem like a sad fact, but it also presents an opportunity: For many children who wind up confined—disproportionately youth of color and youth with learning disabilities—education in confinement may offer the individual attention they need to succeed. However, sustaining their success once they leave is another story, one that requires reform and responsiveness on the part of public schools.

For Roberts, the fact that some students do better at the Academy than in the public school system represents a conundrum. He can make progress with students if he had more time with them. But that would mean longer sentences.

“You’re not in favor of incarceration. Of course, that’s not the goal,” Roberts says. “It’s just that this kind of intensive work needs to be being done in the community. … It’s rare that we have a student here that, on a consistent basis, was attending school regularly.”

Wisdom From the Inside

Approaches used by teachers working in confinement settings are useful elsewhere too.

Prioritize culturally responsive teaching.

Quincy Roberts, a teacher at Maya Angelou Academy, sees his classes every day filled by children of color. Most of his students have never had much success in school. Roberts wishes the youth in his program had come from school settings that honored their identities and offered topics and texts that were more relevant to their lives. “It’s essential for [students] to see that you have some recognition of who they are,” Roberts says.

Look for unidentified special needs.

Disruptive students are often acting out because they’re frustrated by an undetected learning disability.

“In shorthand, it’s easier to be bad than to be perceived as stupid,” says University of Maryland Professor Peter Leone, who specializes in behavioral disorders.

The answer? Instead of immediately punishing disruptive students, consider whether they might need targeted academic services.

Utilize behavior management other than discipline.

La Crosse (Wisconsin) School District juvenile detention teacher Tamara McRoberts works with students she knows are dealing with tough problems and—often—trauma; students in public schools might be going through similar issues that are unknown to educators. McRoberts has learned to recognize when a student needs compassion rather than discipline. “I’m good at reading if someone needs to take a break, or I just throw a piece of paper at them and tell them, ‘Just write.’ They’re really mad, and they need to just get it out,” McRoberts says. Seeking professional development in trauma responsiveness and behavior management is one way educators can expand their toolboxes.

Keep things moving.

At Maya Angelou Academy, class activities are scheduled and timed to keep things moving and minimize disruptions. Each class starts with students grabbing their subject binders and doing a “warm-up” exercise (an approach partially borrowed from Doug Lemov’s practices outlined in his book Teach Like a Champion). Each class ends with a final quiz or problem, and then binders and materials are returned. Keeping the pace predictable and swift also keeps the students focused.