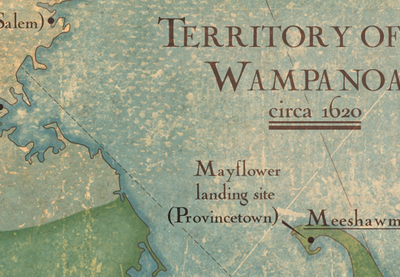

A few days before Thanksgiving, an email went out to teaching staff at my high school, relaying the standard information about the last days before break. It ended with a section on “Thanksgiving Trivia.” I had been prepared for the typical references to Plymouth Rock and the Mayflower, but when I read, “The Native American Indians who celebrated the First Thanksgiving dinner with the Pilgrims were from which tribe?” my stomach dropped. “Trivia?” “Celebrated?” Are we really asking each other and our students this kind of question? As a Native American, an educator and a member of my school’s Equity Learning Team, I had to say something.

I went back and forth, trying to decide what I should do about the email. I wondered how many others had an adverse reaction to the message or if anyone would say something. I wondered if there would be a retraction. I tried to decide whether I should write from my heart and possibly jeopardize a working relationship with my colleagues. I worried that a reply could lead to the sender’s embarrassment, which was not my intention.

We know that Native American history has been rewritten in textbooks and classrooms, obscuring the side effects of colonialism that Native Americans still have to deal with, day in and out. As educators, we cannot perpetuate misinformation. We know that Thanksgiving is a controversial issue for many Native Americans. A one-day reprieve from systematic murder is not a “celebration” for most Natives: We know what happened the next day, and the day after that, and for centuries afterward.

I wrote a private response, including much of what I have written here. I thought I would just play it safe, save the letter as one of the venting files I create when I need to express myself but feel unsafe doing so publicly. It’s good self-care, and it has helped immensely in the past. But this wasn’t just about me. I care for my coworkers, as I care for the students who could benefit from the conversations that this email might begin. I knew I had to say something to all of us—for all of us. I took the plunge and clicked “Reply All.”

I made sure to stress that guilt and shame were not necessary. This was a teachable moment and a perfect example of the critical conversations that are deep in discomfort but still necessary. In my closing, I emphasized that I didn’t expect a response, but I was hoping for personal reflection on how we all address Thanksgiving with each other and our students.

Shockingly, the supportive responses were overwhelming. Of course, there were some dissenting murmurs throughout the school, but I accept that not all people can be reached. At least I opened a line of communication, continuing to scratch away at the layer of protective silence we all envelop ourselves in from time to time.

For 20 years, I have worked to peel back this silence in my high school classroom as well. I ask my students to study historical documents like the travel journals of Christopher Columbus, in which he refers to indigenous people as perfect for potential enslavement. Bartolome de las Casas’ journals bear mortifying witness to Native Americans being mutilated, slaughtered and raped. Students are outraged when they read this. Once they begin connecting the dots to figure out why these early explorers paint Native Americans in such a negative light, the most impressive class discussions and writing samples bloom from these impassioned learners. And we don’t just do this during the month of November.

I always encourage my students to reflect on the past and compare it to the present and future, so we also look at ways to address contemporary silences. My curriculum also includes current stories; I do not just teach ghosts in my classroom. I want my students to see the ways that people of color are present—despite the struggles of their ancestors—still here and still writing, using it all as fuel for their own light when times grow dark.

It can be difficult, sometimes, to resist a culture that silences some voices from our history and trivializes others. However, as teachers, we are rogue activists, finding ways to tell our kids the truth. I highly encourage everyone to research beyond our textbooks and our comfort, and trust that our students can handle the truth about our collective history. There is a lot of discomfort to work through at first, but if the students know they are safe to share their shock, skepticism and curiosity, you will find that your classroom environment will change as they grow closer through stories of struggle and perseverance.

By taking a risk and expressing myself to my coworkers, I modeled for them the exact action needed to evoke change in our school. I hope that this will pave the way for more educators to take a chance and speak up. In doing so, we also show our students what they will need to do if we all wish to continue making progress in the future.

Watkins has taught high school English for 20 years and is pursuing a second master’s degree in creative writing.