Nicole: An Intersectional Case Study

Ninth-grader Nicole is a mature, creative, hardworking student who gets along well with others. But she’s always late for school, frequently misses her first-period class and rarely submits homework in any classes. Needless to say, her grades are suffering. Nicole’s teachers know very little about her life. When they look at her, they see an African-American student who isn’t doing well. They also see a typical example of the deep racial disparities that exist within absenteeism and dropout rates nationwide.

But a teacher who took the time to peel back the layers of Nicole’s identity would see another characteristic—her socio-economic status—and a more nuanced understanding would emerge. Nicole isn’t just a black student; she’s also a girl from a low-income family who bears the responsibility of taking care of her two younger siblings. To fully and adequately support Nicole, an educator must see her situation through an intersectional lens: recognizing that race-, gender- and class-related circumstances are contributing to her achievement issues.

Legal scholar and law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw, who coined the term intersectionality in 1989, explains.

“We know, if we have a gender lens, that girls are more likely to have to engage in caretaking activities,” she says. “They’re the ones who often have to pick up the slack when mothers are unable to, either because of work or other circumstances. The girls are the ones who prepare the siblings for school, make sure they get to the bus on time, pick them up from school. That might make it difficult for them to get to school on time, contributing to their truancy and ultimately leading to them dropping out.”

What is Intersectionality?

Intersectionality refers to the social, economic and political ways in which identity-based systems of oppression and privilege connect, overlap and influence one another.

Crenshaw introduced intersectionality in her groundbreaking essay “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” In it, she examined the ways in which the legal system handled race and sex discrimination claims, observing that black women—historically lacking race, gender and class privilege—consistently had their discrimination claims denied. Her reflections led Crenshaw to describe intersectionality as “a framework … to trace the impact of racism, of sexism, other modes of discrimination, where they come together and create sometimes unique circumstances, obstacles, barriers for people who are subject to all of those things.”

In Nicole’s case, the problems she faces aren’t just about her multiple identities, but stem from the multiplied oppressions that accompany her particular combination of identities: Her situation reflects the experiences of low-income people more than affluent people, girls more than boys and black students more than white students. Specifically, Nicole must navigate parents who work long hours outside the home plus the standard that, as a female, she must care for her siblings plus low expectations on the part of her teachers.

Social Justice Standards

For more on how to talk to students about intersectionality, see the grade-level outcomes for Identity anchor standard three (ID.3) of the Teaching Tolerance Social Justice Standards: "Students will recognize that peoples’ multiple identities interact and create unique and complex individuals.” Even very young children can learn about intersectionality. For example, the K-2 outcome for ID.3 is, “I know that all my group identities are part of me—but that I am always ALL me."

Oppression, Power and Privilege in the Classroom

Although the term first entered the lexicon in a legal context, intersectionality isn’t just about legal discrimination. In the classroom, educators can use an intersectional lens to better relate to and affirm all students—like Nicole—and to help young people understand the relationship between power and privilege through the curriculum.

For Christina Torres, who teaches seventh- and ninth-grade English at the University Laboratory School in Honolulu, Hawai’i, teaching with intersectionality in mind means “seeing your students as more than just the thing that stands out in the classroom, as far as race or their gender, and understanding that there’s a long background to all those things.” Understanding context is also key, Torres says. “A woman who is Latina in L.A. is going to have a very different experience from someone who’s in the middle of Arkansas. The place matters, too.”

Torres’ ninth-grade class recently read and discussed To Kill a Mockingbird, providing the perfect opportunity to dig into intersections of race, gender and place. “We’ve done a lot of different discussions about femininity and what it means to be a woman,” Torres recalls. “But to push that further, we also discussed what that means for Scout, as a little girl who is white, versus Calpurnia, who is black, and what does it mean for both of them to grow up as women in the South. Especially for Calpurnia, who would say [to Scout and Jem], ‘Kids, don’t do that. That’s what Negroes would do.’”

Torres and her class used this passage as a jumping-off point for a discussion about power, internalized oppression and seeing value in one’s culture and community. At the beginning of the year, Torres had assigned her students to consider where and how they fit into their communities and what makes them feel worthwhile there. Recalling that assignment during the Mockingbird conversation, Torres asked the class, “If Calpurnia talks about her own fellow African Americans like that, do you think it’s easy for her to see value from her culture?” The discussion offers an opportunity to explore why Scout might think it is OK to act a certain way but Calpurnia does not.

Intersectionality 101

Need a brush-up on intersectionality? Watch—and share—our animated video!

Navigating the Intersections

An identity-based discussion that directly focuses on layers of oppression might seem too difficult to navigate in class. But for Torres, raising these issues is a way of privileging her students’ identities, experiences and stories. She hears students talking about race, gender and other identity layers outside of class, giving her the green light to bring up these topics in class. In fact, the arc of Torres’ course begins with students examining their own identities—including instances in which they’ve experienced judgment and bias—and closes with the ways in which they’ve exhibited bias against others. By emphasizing intersectionality, she equips her students with the skills to examine why they believe what they believe, why their beliefs might differ from others’ and to determine how their beliefs might be influenced by power and privilege.

Khalilah Harris, former deputy director of the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans, observes that “adults are responsible for helping students to have a safe space to navigate how they identify themselves and what intersections they see of themselves.” Without this safety, she says, students will struggle to embrace, express and advocate for their multiple identities.

“Not … viewing yourself as intersectional and human limits your own growth,” Harris warns. “It certainly limits the students’ capacity to make the strongest connections they can to the content.”

For Torres, helping students like Nicole navigate the world—and the way the world responds to them—is fundamental to her responsibility as an educator.

“Everything in a classroom is dictated by me,” she says. “Every day kids enter our class, there’s an opportunity for them to be empowered or oppressed. When I don’t consider intersectionality and what they might need, I run the risk of oppressing my kids. ... When we stop seeing our kids as whole people—as whole, nuanced people, with context to gender and race and class—we stop seeing them as real people.”

Intersectionality in the Court System

In 1989, legal scholar and law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw applied retrospective analyses to three discrimination lawsuits, each filed by black women. Presented in “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” these cases gave rise to her thinking about intersectionality and its importance, not only in the legal realm, but also in feminist and antiracist discourse.

The first case she examines, DeGraffenreid v. General Motors (1976), illustrates how the courts at that time interpreted existing anti-discrimination laws, previous legal decisions and plaintiffs’ claims to be members of a protected class. In DeGraffenreid, five black women claimed that their employer, General Motors, discriminated against black women by laying off employees on the basis of seniority during the 1970 recession. Because GM did not hire black women before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, “all of the [black] women hired after 1970 lost their jobs,” Crenshaw explains.

The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri ruled in favor of the defendant, however, stating that, because the layoffs did not also affect white women, there was no legitimate sex discrimination claim; and, because the layoffs did not also affect black men, there was no legitimate race discrimination claim either. “[Black women] should not be allowed to combine statutory remedies to create a new ‘super-remedy’ which would give them relief beyond what the drafters of the relevant statutes intended,” the court stated. “Thus, this lawsuit must be examined to see if it states a cause of action for race discrimination, sex discrimination, or alternatively either, but not a combination of both.”

Crenshaw argued that the court’s failure to see the ways in which sex and race compounded the injustice against the plaintiffs indicated a systemic failure—one that isn’t limited only to black women.

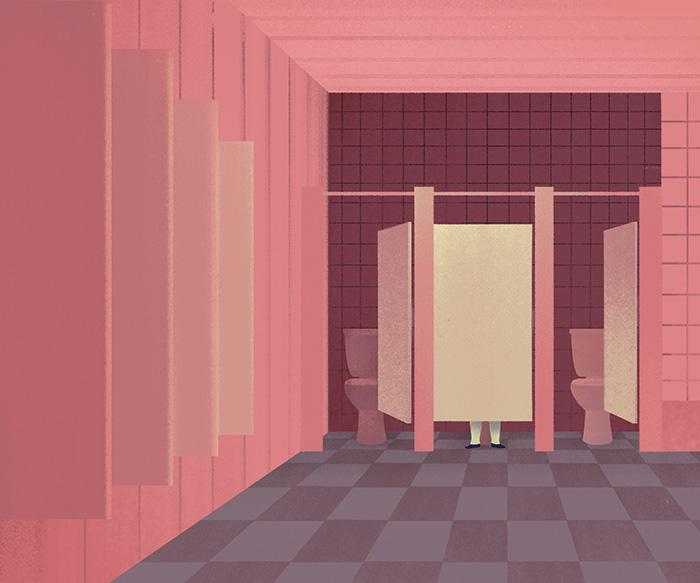

Fast-forward 26 years from Crenshaw’s 1989 examinations to the case of G.G., a 16-year-old transgender student in Gloucester, Virginia, whose school prohibited him from using the men’s restroom. Represented by the American Civil Liberties Union, G.G. took his case to court in June 2015, arguing that his treatment violated Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which protects people from sex discrimination in schools. The U.S. Department of Justice agreed with G.G.’s intersectional argument, making this statement in a brief filed in June 2015: “Discrimination based on a person’s gender identity, a person’s transgender status, or a person’s nonconformity to sex stereotypes constitutes discrimination based on sex. As such, prohibiting a student from accessing the restrooms that match his [or her] gender identity is prohibited sex discrimination under Title IX.” The district court later dismissed G.G’s Title IX claim and denied his injunction against the school board. But, in April 2016, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the dismissal of G.G.’s Title IX claim and ruled that the district court must reconsider G.G.’s injunction against the school board.

In this case, the school’s reaction to the combination of G.G.’s sex assigned at birth, gender identity and gender expression—important elements that make G.G. who he is—directly contributed to the discomfort and stigma he experienced at school when it came to using the restroom.