In West Virginia, a public high school refuses to remove a painting of Jesus that hangs outside the principal's office. In Georgia, legislators vote to include the Bible in a statewide public school curriculum. And in New York, officials prohibit the scheduling of standardized tests on religious holidays, after protest over a statewide exam held on a Muslim holy day.

For decades, educators have wrestled with how to handle the increasingly diverse religions of an increasingly diverse student body. Sometimes, the line between church and state – what schools can and cannot do under the Constitution – can feel confusing and slippery.

Today, religion has become a subject one high school teacher calls even more controversial than teaching sex-ed. Teachers feel ill-equipped to talk about it. In a post-9/11 world, students increasingly face harassment for what they believe.

And yet, today's students will interact with a far more pluralistic society than their parents or grandparents did. Some educators see in this a call for urgency. If faith-based intolerance is ever to be confronted, they say schools are exactly the place religion should be addressed.

"Schools are the one place where all of these different religions meet," said one educator. "It follows that religious diversity must be dealt with in school curriculum if we're going to learn to live together."

For the past seven years, the school district in Modesto, Calif., has done just that.

After a divisive, public battle over the role of tolerance in the city's schools, a small group of teachers developed a world religions curriculum for every 9th-grade class in the district. Now, Modesto stands out as the only school district in the country that mandates a world religions course for high school graduation.

New research shows the course has increased students' respect for religious diversity. And teachers here hope their efforts will encourage other districts across the country to follow their lead.

California's 'Bible Belt'

Modesto was a surprising birthplace for such a risky venture. The city of about 200,000 sprawls across Northern California's Central Valley, about 90 miles east of San Francisco. Residents call the area the "Bible Belt of California," for its conservative roots and vocal evangelical community. But a growing immigrant population has infused Modesto with a jolt of religious diversity, adding to the mix growing numbers of Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs.

Several years ago, a move to add gay and lesbian students to the school district's safe-schools policy, titled "Principles of Tolerance, Respect and Dignity," caused an uproar among local religious leaders. The conflict lasted for months. Finally, district officials turned to Charles Haynes, director of the Arlington, Va.-based First Amendment Center, for help.

"I thought I was meeting with the committee appointed to deal with this issue," Haynes said. "I went into the school cafeteria, and there was a 'committee' of about 115 people. Everyone wanted a voice in this issue – gay and lesbian students, local pastors, teachers, administrators – but people were speaking past one another."

He suggested they abandon the word "tolerance" – many religious conservatives thought it meant the school district was "taking a stand on homosexuality." Instead, Haynes asked the group whether all students, regardless of their beliefs or lifestyle, had the right to be safe at school and free from bullying. Everyone agreed.

"The pastor who was in charge of the opposition stood up and said, 'If this is what the district means, we're fully for that. We're Christians – we don't want anyone beat up or hurt'," Haynes recalled. "A gay student stood up and said, 'Well, that's all we want, too.'"

Together, they crafted a new safe-schools policy grounded in the First Amendment right of free expression, and the responsibility to safeguard that right for others.

The school board unanimously adopted it.

From the policy stemmed many new initiatives, such as a character education course and human rights clubs. Among them was a new focus on teaching about religious diversity.

"When you don't know about something, you fear it – and when you fear something, you become more likely to strike out against it," said Modesto teacher Yvonne Taylor. "We wanted students to understand that even if we disagree with a group of people, they still have the right to be here."

'You Can't Teach Religion'

Modesto requires that every 9th-grader in the district enroll in a semester-long world religions course. Ninth grade made sense – students were old enough to handle the subject material, and the emphasis on religious diversity happened to coincide with the district's desire to enhance the 9th-grade history and social studies curriculum. Since then, state standards have changed – the world religions course no longer fulfills specific state curricular requirements, but it's been so successful in changing attitudes that school officials decided to keep the course in place.

"(At the beginning of) every semester, the kids say, 'You can't teach about religion!'" said Jennie Sweeney, the curriculum coordinator who organized the course's development. "And we say, 'Yes, we can – we're going to teach about religion, we're not going to teach religion.' There's a big difference." By law, public schools cannot show preference to one religion. Yet they can legally address religion in ways that are both fair and neutral.

Modesto's world religions course is modeled after the same First Amendment principles that guided the safe-schools policy. "You can be staunch in your own personal beliefs, yet also staunch in respecting and protecting the religious liberties of other people," said Sherry Sheppard, who teaches the course at Modesto's Johansen High.

The class begins with an overview of First Amendment rights and responsibilities. Teachers emphasize the importance of respectful inquiry, and students learn catch-phrases for keeping each other in check to minimize disrespectful remarks.

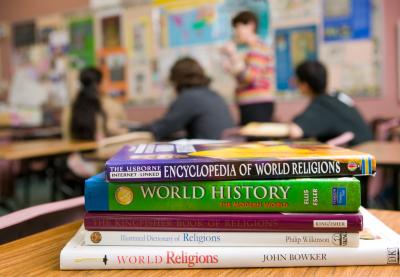

Next, students delve into six religious units, covering Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism and Sikhism. The class spends equal time on each unit, studying the history of each faith, the basic tenets, and examples of each religion's societal significance (i.e., Hinduism's influence on Gandhi and the concept of nonviolence).

For the sake of neutrality, teachers aren't allowed to share their own faith backgrounds during the semester, nor are outside speakers welcome. Every class in the district reads the same textbook, watches the same videos and follows the same scripted lesson plans. "It can almost feel prescribed," Sheppard said, "but it prevents teachers from sliding in their own biases."

Students, though, are encouraged to share their own beliefs and ask questions.

As a result, the course provides a safe space to talk about sensitive issues in ways that otherwise might be inappropriate or impolite. It's not unusual, for example, for students to come to class with questions about the man wearing a turban in the grocery store, or a person sporting some other form of religious garb.

"They get excited as the course goes on, because they realize it's something they've never learned about before," said Taylor, who also teaches the course at Johansen.

During the course's inaugural semester, a student who was Buddhist left school on a Friday afternoon with a full head of hair and, to everyone's surprise, returned Monday with a shaved head. His uncle had died, and, in his honor, the student became a Buddhist monk over the weekend, committing to six weeks of service to the temple.

The world religions course became a forum where the student could speak openly about his experience. Because the class had spent weeks exploring different aspects of multiple faiths, classmates viewed the student's decision with interest and respectful curiosity instead of derision.

"For a lot of non-Christian kids, they feel validated at school for the first time," Taylor said. "They say, 'I have a voice now, I'm proud of who I am, and now I can share that and talk about it in a safe environment.'"

The district provides an opt-out policy for parents uncomfortable with the curriculum. Since the program's launch seven years ago, fewer than ten parents have taken advantage of the policy.

"My parents thought it was really interesting," said Lakhbir Kaur, now a senior. "They asked a lot of questions and talked about it at dinner. There was some stuff I learned (during the class) about my own religion that I didn't know, and I went home and asked my mom about it. It was eye-opening."

'Not Different After All'

In May 2006, researchers from the First Amendment Center released the results of a comprehensive study of Modesto's world religions course. They wanted to know if teaching about diverse religions had any impact on students' religious tolerance.

"We've never really known what effect it would have if we taught more about different religions in public schools," Haynes said. "We've always said it was a good idea – but in terms of empirical evidence, what it does for our kids, this study is the first indication of what it might do."

Researchers interviewed students before, during and immediately after the semester, and again six months after the course ended. Over and over, they found that students had become more tolerant of other religions and more willing to protect the rights of people of other faiths.

In their own words, students say the course broadened their views and empowered them to fight back against faith-based bullying.

"I didn't know anything about any religion other than mine," said Kristin Busby, now a senior. "By the end [of the semester], we were all much more accepting toward one another. You realize that we're all not that different after all. We all have these necessities, and these religions provide for those necessities, just in different ways."

Added Ishmael Athneil, a freshman: "If some of my friends are talking about someone and saying, 'Wow that's weird,' now I can jump in and say, 'Well, actually, this is why he does that.'"

However, this increase in religious tolerance was not accompanied by a change in students' personal religious beliefs, a finding of huge interest to researchers. "This is important," Haynes said. "It means that learning about different religions will not undermine the faith of the family."

Students who began the semester with strong religious convictions ended the semester with the same beliefs.

"My mom and dad were biased against this course," said 9th-grader Richard Dysart. "They were afraid I'd convert and get confused about what my family believes. But if you're part of a culture, you won't switch just by learning about how other people live."

The course's ability to offset religious intolerance was put to the test at the beginning of its second year.

"We had just made it through the first year without a single complaint from a parent," Sheppard said. "We walked into that September feeling kind of cocky. Then 9/11 happened."

The training for the world religions course prepared teachers to handle the issues and questions that arose that year.

"We realized we'd have to be very delicate with this, making sure the difference was explicit between Islam as a religion and the people who committed that act," Sheppard recalled. "We still emphasize that point when we get to Islam."

Across the country, reports of schoolyard harassment against Muslim students escalated in the months immediately following 9-11. In Modesto, not a single act of harassment was reported against a Muslim student during the 2001-2002 school year.

'Not In This Alone'

These results, teachers said, didn't happen by accident.

The teacher-led committee that created Modesto's curriculum worked closely with the local community during the course's development. First, teachers identified each religion that would comprise the curriculum; next, they worked in teams to research the different faiths.

Part of that research involved field trips. Teachers toured several houses of worship and invited religious leaders from multiple faith backgrounds to attend a meeting at the school, to explain the purpose of the curriculum and ask for input.

Before the course launched, teachers asked local religious representatives to review the textbook. "There are an equal number of pages given to each religion," Sweeney said. "We knew they would count."

In addition, the book contains a section on nonbelievers; whether teachers delve into atheism (some do, some don't) seems to be one of the few ways that different classes deviate from the curriculum.

For all of its successes, researchers did identify some curricular shortcomings. They faulted the Modesto course for failing to address the negative aspects of religions, to give students a more accurate picture. Researchers questioned the policy of forbidding guest speakers, and they suggested that Modesto's teachers would benefit from more robust training.

Teachers, for their part, questioned these criticisms. "They weren't sensitive to what we were trying to do and the limitations we faced," Sweeney said.

Currently, teachers who volunteer to instruct the course must first attend a 30-hour workshop on how to teach about religion. In addition, the district tries to provide time and space throughout the year for the world religions teachers from each campus to meet, share ideas and discuss concerns.

While this in-service training isn't as frequent as the researchers would like, it does add value to teachers' experiences. "We know we're not in this alone," explained Taylor. "I think this is one of the best things I've done in 35 years of teaching."

'If Here, Anywhere'

The moral of Modesto's success isn't that every district should rush to create its own world religions requirement. "Not all districts can, because there simply isn't room in the curriculum," Haynes said.

But schools can reconsider how and what they teach when it comes to religion. More schools could offer world religion electives, improve the religion sections of their social studies curricula, or implement school policies that are more inclusive of diverse faiths (i.e. not scheduling tests on religious holidays).

Specifically, Modesto's success suggests more schools should do the following:

Improve teacher training.

"The biggest barriers (to teaching about religion) are not parents or the community or the law," said Haynes. "The biggest barriers are that teachers do not feel prepared to teach about religion." Researchers at the First Amendment Center suggest a world religions requirement for every pre-service social studies teacher in the country, religious studies courses incorporated into teacher training programs, and improved in-service training for teachers already on the job.

Understand the law.

Many school districts still think it's constitutionally problematic to discuss religion in schools. Some districts think neutrality means silence. Others address some religions but exclude others (i.e. an elective on the Christian Bible, but no equivalent for other religions). "Neutrality, in a word, means 'fairness,'" said Haynes. "School officials are supposed to be the fair, honest, neutral brokers who allow various voices to be heard."

Work with communities, not against them.

Parents and religious leaders can be seen as the enemies of efforts to address religious pluralism in schools. But teachers in Modesto attribute their success, in part, to how well they worked with the community. As a result, Sweeney said, parental complaints have been minimal: "Because we have support from the religious community, I think they've told their members not to worry about this."

Consider it a core mission.

"Students need to learn these things," said Modesto student Edward Zeiden, of his school's world religions course. "It should be required, just like history."