At age 15, my grandfather, born into slavery and barely able to read and write, hitched his tuition -- a steer -- to a rope and walked 100 miles across Kentucky to knock on the door of Berea College. The school admitted him and, 14 years later, asked him to deliver the commencement address when he finally graduated.

"In every cloud," my grandfather said, the pessimist "beholds a destructive storm, in every flash of lightning an omen of evil, and in every shadow that falls across his path a lurking foe. He forgets that the clouds also bring life and hope, that lightning purifies the atmosphere, that shadow and darkness prepare for sunshine and growth, and that hardships and adversity nerve the race, as the individual, for greater efforts and grander victories."

This summer, I thought of my grandfather and his steadfast optimism as I read the deeply divided Supreme Court's 169-page decision on school integration, a ruling that severely undercuts our nation's ability to provide equal educational opportunities for its children. Four conservative members of the Court went so far as to suggest that our schools may not take race into account to combat "de facto" segregation and the injuries it inflicts.

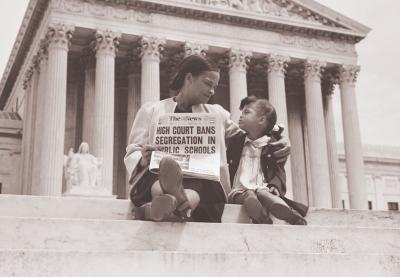

How very far we have fallen since that Spring day in 1954 when a unanimous Supreme Court mustered the moral courage in Brown v. Board of Education to demand, in 11 simple and eloquent pages, that our nation afford equal -- and integrated -- educational opportunities, so that our shameful tradition of white supremacy might be undone. How very hard it is to maintain optimism -- to see the sunshine my grandfather always saw behind dark clouds -- when contemplating what the Court has done in 2007.

Our schools have long been held up as our most important democratic institution, pathways to class mobility and generational progress. A public educational system that is fully integrated and treats minorities and whites equally is the antithesis of the larger society, which has been and remains profoundly segregated and unequal.

I once heard Minnijean Brown reflect on her experiences as one of the heroic Little Rock Nine who integrated Central High School in 1957. Someone asked why she kept coming back to school day after day, despite daily harassment and intimidation that would have driven most people away.

From the ferocity of her enemies, she said, "I knew there was something precious inside that school," and she was more determined to get it than they were to keep it from her grasp. Minnijean and the Supreme Court Justices who delivered and supported Brown understood schools as pathways to righting the wrongs of societal racism.

But today's Supreme Court has embraced another vision for American education: schooling as an instrument for reproducing the class and race privilege of the larger society. At the dawn of the 21st century, one in six African American children still attended what researchers call "apartheid schools" -- schools that are virtually 100% children of color -- and no school district in America has managed to create equal educational opportunities within these schools on a large scale or in a sustained manner, particularly at the secondary level.

Today's Court has turned its back on the millions of black and Latino children currently trapped in highly segregated, underperforming schools, leaving them to hang on the ropes of racial and economic disenfranchisement. The Court has paved the way for many more children of color to join them by outlawing the modest means numerous districts have adopted to promote racial diversity and overcome racial isolation. It has denied the very notion that our nation's schools should serve as equalizers.

Three years ago, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Brown decision, the country asked itself whether our nation had fulfilled Brown's promise. Many emphasized that Brown had brought about a sea change in American life — tearing down the walls of segregation and serving as an impetus for equal rights for groups other than African Americans. Others pointed to the facts that our schools were resegregating and that society was still marked by stark inequalities. The Supreme Court’s recent decision is likely to be remembered as Brown’s final epitaph.

A public educational system that is fully integrated and treats minorities and whites equally is the antithesis of the larger society, which has been and remains profoundly segregated and unequal.

I think again of my grandfather, a man who walked 100 miles to a college that had not admitted him and who, once accepted, labored 14 years for his diploma. His actions are what speak most profoundly to me in this moment: We must persevere. We must strengthen our resolve against the destructive storm that has descended upon us.

If schools can no longer be used to address our country’s racist traditions, then we as a country must attack racism by other means. If our schools are no longer allowed to offset the consequences of persistent residential segregation, for example, then we as a country must attack the problem directly. If our schools are not allowed to serve as equalizers towards remedying the vast inequalities that continue to fester in our country, then we as a country must confront those inequalities head-on. If we cannot rely on the courts, then we must lobby the legislatures.

Only with a renewed commitment will we be prepared to undertake, as my grandfather would have said, the "greater efforts" towards the "grander victories" this new era requires. Only with renewed commitment can our country become the nation it should be. Only with renewed commitment will we fulfill the promise of Brown.