On September 4, 1957, 16-year-old Minnijean Brown headed off to her new school, Central High in Little Rock, Ark. She was nervous, and not just because she'd be a "new kid" in school. She and eight other black youths were slated to become the first African Americans to attend all-white Central High.

When they arrived that morning, the "Little Rock Nine," as they would become known, were greeted, not by teachers or the principal, but by the National Guard. Gov. Orval Faubus had mobilized the troops in order to keep the teenagers out.

The next day, the youths were greeted by an angry white mob and again were turned away.

On day three, the teens made it to their first class, but were sent home after a violent mob gathered outside the building.

President Eisenhower eventually intervened, sending federal soldiers to walk alongside the Little Rock Nine as they went from class to class. Still, for Minnijean and her peers, the 1957-1958 school year would be marked by almost constant harassment.

The following year, the governor closed all public schools rather than allow integration to continue. The Supreme Court soon responded to Faubus' actions, ruling that fear of social unrest or violence, whether real or constructed by those wishing to oppose integration, did not excuse state governments from their obligation to integrate schools. Little Rock schools finally opened to all children, as did schools across the nation.

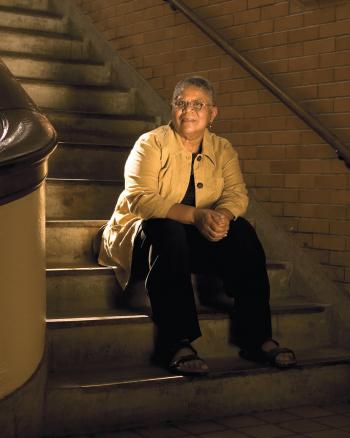

Fast-forward 50 years and meet Minnijean Brown Trickey: public servant, activist, educator.

Trickey's commitment to peacemaking, diversity education and social justice advocacy has earned her numerous awards, including the Lifetime Achievement Tribute by the Canadian Race Relations Foundation. She, along with the Little Rock Nine, received both the NAACP's Spingarn Medal and the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation's highest civilian honor. She's been on Oprah and profiled in People. There's even an award-winning documentary about her life, Journey to Little Rock: The Untold Story of Minnijean Brown Trickey.

Today, Trickey holds the Shipley Visiting Writer Fellowship at Arkansas State University, is deeply involved in the Little Rock Nine Foundation and serves on the faculty of Sojourn to the Past, a ten-day interactive history course that has brought more than 3,000 high school students to the Deep South to study the Civil Rights Movement.

It was during one of Sojourn's visits to Montgomery, Ala., that Trickey sat down with Lecia Brooks, director of the Civil Rights Memorial Center, for a candid discussion about that pivotal year at Central High.

History books rarely capture the true essence of events. What did it really feel like to walk through the halls of Central High School, to sit in its classrooms, that year?

It's almost impossible to describe: stepping on heels, calling names, spitting, kicking us. We (the Little Rock Nine) were never comfortable.

We acknowledged that a specific number of people, probably 50 to 75 students, were really behind the havoc in our lives, not everyone. Most students were neutral; they didn't do anything. And for each of us, there were probably two students who would openly smile or say "hi" to us.

We were really isolated though. The school purposefully placed us in separate classes. Only two of us ever shared a class period together. Over the years, as I've continued to read about it, analyze it and think about it, I believe the school separated us to set us up for failure — and to ensure that we could never serve as witnesses, as corroborators, of the abuse we each endured.

Did any white students step out as real allies, going beyond a smile or a "hi"?

There was one girl named Mary Anne who would actually walk beside me in the hall. We didn't become friends or anything, but I knew she put herself at great risk. I thought she was brave.

The truth is, though, her kindness couldn't balance out the bad.

I understand the human need to believe people are fundamentally kind, and young people in particular don't want the world to be unfair. Even small children have a strong sense of what is fair and what isn't. People want to know if there were nice kids, because they want the world to be fair, but what happened at Central High was not fair. And almost all of the white people were either mean or neutral — "silent witnesses" whose silence spoke volumes.

I don't think the white students knew how to be fair. White supremacy and black inferiority are part of the American training. They couldn't conceive of me as an equal person.

When you were growing up, part of that "American training" was segregation. What was it like to live in segregated Little Rock?

Before Central, Little Rock didn't feel hateful to me. You just didn't go where you couldn't go, and you didn't challenge anybody. I don't remember anyone ever saying to me, "Don't talk back to white people." The rules of segregation were simply understood.

As a child, I knew I lived a separate life. White people lived someplace else and did different things. A white person never told me they hated me. I didn't know any white people!

As a teenager, I knew white kids could do fun stuff that we couldn't. We couldn't go in the drug store and get an ice cream float. When we went shopping, we had to go to the back of the store to buy shoes. There was always a feeling that it was unfair — I shouldn't have to go to the back — and yet, it's how things were. Segregation was a way of life.

Before Central High, I knew racism as condescension. At Central, I came to know racism as hatred.

What had you expected the year at Central to be like?

I was a just a regular teenager, one who liked to sing "do wop" songs and read books. My family expected me to do well. "Do well; do it right." Those were the expectations.

Of course, I understood the moment — opening up the facilities at Central to everybody, eliminating two systems of education, one deeply inferior and one greatly superior — was bigger than me, than us, than the Little Rock Nine. As the school year unfolded, I came to sense a great obligation. The obligation — knowing I had to be a "credit to my race" — is what I remember most profoundly from that year.

You just described yourself as a "regular teenager," and yet history tells me, and I deeply believe, that you are an extraordinary person who has done extraordinary things.

Well, you can't help it when you're in it. Your resistance just flares up. Resistance came into my body with the mob on the second day.

"If they're willing to behave like this," I remember thinking, "I'm coming back."

And it was like that every day: "I'm going to school, because I want to see what they've thought of doing to me today."

I'm not that teenager anymore, but she's still with me. And that's one of the reasons why, when I'm sharing my story with young people, I always reach out to them: "I know that you're thinking and I know that you're analyzing, and I know that you notice things, because I did."

Turn on the news today, and it's all about blond movie stars, millionaires and other "super people." Young people know that's a distraction. They have real concerns — about war, about the environment, about racism, about many things. Young people see the problems in today's world, just like I did 50 years ago.

Discussion Questions

- Trickey shares that she's experienced racism as both condescension and hatred. Define racism. How does it affect your life, and the lives of others?

- In what ways does racism remain a problem in U.S. schools?

- Trickey states that the rules of segregation were simply understood. Are there unstated rules at your school that isolate and unfairly affect certain groups?

- The Little Rock Nine made history by becoming the first African Americans to attend Central High. What boundaries have you crossed at school or in your community? How did it feel? How did others react?

- If Trickey visited your school today, and compared your school experience to her school experience, what changes in attitudes and opportunities would she discover? What hasn't changed? In your school, does kindness balance out the bad?

- Trickey's service as an activist and educator has earned her numerous awards. Imagine you are receiving a social justice award fifty years from now. What earned you the award? What inspired you to make a difference?