Erin, a suburban Minneapolis teenager, began to grapple with serious depression and anxiety in the seventh grade. By ninth grade she was cutting herself dangerously, and she spent several weeks in residential treatment. But facing hostility at school proved to be the hardest part of her struggle.

After word of her illness spread, “I lost friends rapidly,” Erin says. A barrage of verbal attacks marred her days. “I was called crazy, and kids said, ‘Why did you come back anyway? Nobody likes you. Why don’t you kill yourself? You’d be better off dead.’”

“It made me feel a lot worse and made me not want to go to school,” Erin recalls. When teachers heard the taunts, “they turned around and acted like nothing was said.” Her mother sought help from school staff but says she was rebuffed. The taunts prompted a downward spiral in Erin’s life that ended with her return to residential care. Rather than attempt to return to her school, Erin finished high school online.

Erin's experience of social rejection at school is quite common, suggests research on teenagers with mental health problems. In one study, nearly two-thirds of teens coping with mental illness reported stigma from their peers. In another study at four middle schools, just half of students said they’d be willing to sit next to a classmate with mental illness. Although hurtful stigma is only one of myriad challenges faced by teens with mental health issues, it is an area where classroom teachers can provide immediate assistance.

Adolescence is a uniquely painful time to confront mental health challenges, experts say. “There’s a great push toward peer conformity, and being different in any way is perceived as a negative; it carries a stigma,” says Joseph Allen, director of the Virginia Adolescent Research Group at the University of Virginia.

“Normalizing” challenges with mental health is the key to reducing stigma among teens, Allen says. “If they see that ‘Whoa, this is not so uncommon,’ they can feel better about dealing with their own problems and others that have them.”

A study conducted by the Adolescent Communication Institute at The Annenberg Public Policy Center showed that discovering that people can be successfully treated for mental disorders also curbed negative stereotypes. “You have to give kids facts that counter their stereotypes, and then many are open to change,” says the study’s leader, Dan Romer.

Wendy Sunderlin, who teaches life skills classes at St. Paul’s School for Girls in Brooklandville, Md., hands out a needs-assessment survey at the start of the year to find out what students would like to learn about improving mental well-being. She uses this survey to steer her teaching. And she gently evokes personal disclosure. “I have them sit in a circle, and I ask something like, ‘How many of you have been affected by depression?’ A surprising number seem to raise their hands, and right away it takes away the ‘I am alone’ shame that kids feel.”

Sunderlin also assigns students a final project about a health topic of their choice—they often select a mental health issue. Her students have built informative websites on mental illness topics that remain live after the end of the school year to continue educating the entire school community. Students have created posters and paintings titled, “This Is What Anxiety Looks Like,” and they’ve written poems about mental illness. “Their number one concern is how they’re viewed by their peers, and their number one influence is their peers. So I have them use what they’ve learned in my class to educate one another,” Sunderlin says.

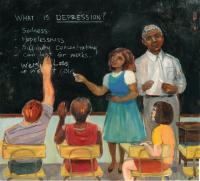

At Commack High School on Long Island, N.Y., teachers decide on a schoolwide theme around a social or emotional issue every year. Often it has been a mental illness topic, such as depression, says school psychologist John Kelly. That theme is then carried out across the curriculum. English and social studies teachers incorporate the topic into their curriculum. There are plays, dance concerts and spoken- word performances. Photography students take pictures keyed to the theme. Physical education teachers may discuss athletes with mental health issues.

“Whole classes are working on this; we’re talking about it a lot. And we find it gives kids permission to express their own struggles. It breaks down the shame and fear,” says Kelly.

All of us have problems, none of us are perfect, so leave your masks at the door.

The credibility of slightly older classmates has proven a powerful stigma-fighting tool for Kelly Iacobucci, who teaches a ninth-grade health class at Bishop O’Connell High School in Arlington, Va. Once, an 11th-grader who was a survivor of sexual abuse volunteered to visit Iacobucci’s class.

The volunteer discussed her challenges with body image and self-esteem. “It was amazing to see how [the students] opened up and shared after she came in,” says Iacobucci. One girl disclosed that she was receiving therapy for an anxiety disorder that impels her to pull out her hair. “Suddenly, another girl across the room said, ‘Oh my goodness, I have the same thing!’ It was mind-boggling, and I said, ‘See, if we shared more often we could support each other,’ and I think they got it. I tell them, ‘All of us have problems, none of us are perfect, so leave your masks at the door.’”

Alex Winninghoff, formerly an English teacher at Federal Way High school in Federal Way, Wash., posts colorful infographics on her walls to show that illnesses such as depression and anxiety are common in young people. “That communicates I’m available to discuss these issues with them—and they do come to me,” says Winninghoff.

Like Sunderlin, Winninghoff distributes an interest survey as the semester starts to help her get to know students better and develop personal relationships with them. If a student looks down, she’ll put a sticky note on his desk that says “I’d like to chat with you after class,” and then she gently asks about what’s going on. Self-stigma around mental health problems can prevent kids from getting care, she says. “I’ve had them burst into tears and tell me about something they need help with and have been too ashamed to tell anyone.”

Monitoring strategies also can help educators identify any stigma at their school before it can cause students harm. For example, at Bishop O’Connell, students deemed to be at risk are matched with compatible teacher-mentors who frequently check in to make sure the students are faring OK. Among those mentored are students returning from residential care for mental illness, says Erin O’Malley, the dean of faculty. When harassment is identified early on, it can be dealt with before it escalates.

Kids with mental illness often long for help; they want to overcome their own shame and to not be teased about their problems, teachers say. “But they don’t want you to label them or point to this as a terrible deficiency,” adds Winninghoff.

Even one teacher can make a huge difference.

Katie Williams, 21, knows that for sure. She had fought serious obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression since age 10, and by 11th grade was hiding her condition to avoid rejection. But Williams’ history teacher talked to Williams about her strengths.

“Nobody had ever done that before,” says Williams. “She told me I was so compassionate because I’d experienced so much stigma. I could help others. She asked me to become a tutor for kids who were the first in their family to try for college, and I did it. She kept saying, ‘Your illness is not you, it’s just a part of you.’ … Really, she helped me to stop stigmatizing myself, and that made all the difference.”

Her history teacher’s support prompted Williams to disclose her illness to classmates, who were mostly accepting, “and those that weren’t, they just dropped out of the picture for me,” says Williams. Her grades shot up, and now Williams is a senior at California State University, Sacramento, where she speaks to college-level classes to reduce stigma around mental illness.

“That teacher changed the course of my life,” Williams says. “She’s the reason I made it to college and am doing so well now.”

Myths vs. Facts on Mental Illness

MYTH

Mental health problems are rare in childhood and adolescence.

FACT

About one out of five U.S. children has a diagnosable mental disorder in any given year. Half of all lifetime cases of mental illness begin by age 14.

MYTH

Very few students become so troubled that they think about committing suicide.

FACT

About one out of six high school students say they have seriously thought about attempting suicide.

MYTH

Males and females are about equally likely to become depressed.

FACT

Before adolescence, rates are the same. From midadolescence through adulthood, depression is about twice as common in females as in males.

MYTH

People with mental illness are often violent.

FACT

Many people with mental disorders are not violent, and most violent acts are not committed by people who are mentally ill. Overall, they’re responsible for just 5 percent of violent crimes. Those with serious mental disorders are, however, far more likely than others to be victims of assault and rape.

Sources: National Alliance on Mental Illness, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, Mentalillnesspolicy.org