Ninth-grader Sadie Bauer was walking hand-in-hand with her girlfriend in a hallway of Kennewick High. It was a brave act of affection, considering bigoted attitudes toward same-sex relationships in this rural area of Washington State.

The words rang out, “You ******* dyke!”

Sadie braced herself for more profanity and slurs, when out of the crowd came one of the school’s math teachers. The teacher was probably a head shorter than the bully she confronted, recalls Sadie. But she still got in the name-caller’s face until he backed off. Later, Sadie’s tormentor came up and apologized.

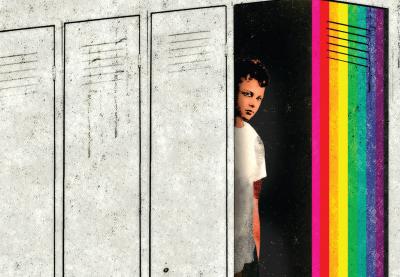

For Sadie, now 19, the teacher’s intervention was a memorable moment in an otherwise miserable high school career. “School was horrible,” she remembers. “I was so stressed out. There were only two or three teachers I could talk to about being gay.” She describes being so fearful of the school locker room that she lied to her doctor to get a note to escape the teasing and taunts. By sophomore year, Sadie says, she showed up at school only twice a week. In the end, dropping out was a mere technicality, though she proudly shares that she recently earned her GED.

Being an LGBT youth in America has never been a Gay Pride Parade, no matter the community setting. But most rural schools prove an especially unhappy and dispiriting place for kids whose sexuality or gender expression does not fit within community expectations. Those are the findings of researchers for the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN), published in the Journal of Youth and Adolescence last August.

“We keep finding that youth in rural areas—whether gay or perceived as gay—are more likely to be victimized verbally and physically,” says Dr. Joe Kosciw, lead researcher in the national study. In fact, the study found that these students are more at risk in rural districts than in urban districts with a history of bullying problems. “In addition, rural schools and communities often lack resources such as Gay-Straight Alliances or youth centers that can help offset the negative experiences of victimization.”

Where might help for these students come from? The work of GLSEN and other national groups are increasingly entering frays to offer support. But as LGBT teens are eager to share, the intervention of friendly math teachers is not to be underestimated. “You learn very quickly to identify safe teachers,” says Korey Gaddis, also a former Kennewick High student. “You pick up on their vibe.”

For a decade now, GLSEN’s biannual National School Climate Survey has revealed and quantified the bias encountered by many LGBT students in middle and high schools across the United States. Lowlights from the most recent 2007 survey include 86 percent of LGBT students reporting verbal harassment; 61 percent saying that they feel unsafe at school because of their sexual orientation; 33 percent indicating that they have skipped a day of school in the last month due to feeling unsafe; and 22 percent reporting that they have been physically assaulted because of their sexual orientation. The idea that rural students are at greater risk for these abuses sounds alarm bells for LGBT youth advocates.

Out in the Country

As Dr. Kosciw and his fellow authors discuss in their article, “the overall climate of a school is … influenced by and potentially reflects the attitudes, beliefs and overall climate of the larger community”—for better and worse. For rural areas, the “better” includes local recognition of schools as integral parts of the community, with area businesses and service organizations actively supporting school programs. Schools and students may benefit from strong values promoting the care and education of “their kids.”

The “worse” is most evident when school and community leaders encounter values they consider alien. Many rural residents pride themselves on their conservative social and religious values, and distrust those whose identities and lifestyles fall outside those strictures. The relatively recent emergence of the national gay rights movement, and the fact that gay kids are growing up and coming out in their small towns, presents unnerving challenges to many rural residents and their ideas of how the world should work. These are among the views put forward by Mary L. Gray in her insightful book, Out in the Country: Youth, Media, and Queer Visibility in Rural America.

Mark Lee has spent the last three years trying to communicate across this cultural divide in the Tri-City Area. In 2006, Lee moved from urban and progressive Portland, Oregon, to this farming region that includes the cities of Kennewick, Pasco and Richland. “The Tri-Cities are an incredibly conservative, white, religious community,” Lee says. He quickly recognized the lack of an oasis for gay kids, and soon after his arrival established the Vista Youth Center, dedicated to the wellbeing of LGBT youth, ages 14-21. The center offers a support network and social outlet for dozens of teens and young adults, some who drive more than an hour each way for meetings.

Lee has witnessed the struggles of area LGBT students close up. “[LGBT] kids at Kennewick High learn quickly how to sneak in and out of school so as not to be screamed at,” he says. “Youth have gotten beat up. They have to deal with frequent insults, sometimes from teachers as well as classmates. With all the bullying and harassment, I personally don’t know how they make it through the school day.”

At the same time, Lee describes the positive effect even a ray of support has on LGBT youth. “I’ve seen radical change in most young people who come to [Vista Youth Center],” he says. “I’ve seen them go from belligerent and depressed to being sweet, regular kids.”

“It’s an amazing place,” adds Sadie about VYC, “a home away from home where I can be myself. If the youth center wasn’t here, I don’t know what I’d do. It’s a lifesaver.”

Lee recognizes that part of his mission is to reach out and educate community leaders about LGBT youth. He has brought in panels of educators to listen and respond to concerns and complaints from students. He plans to invite local ministers and church leaders to discuss the area’s religious intolerance for homosexuality, which frequently fuels gay-bashing. “There’s a lot of consciousness-raising that needs to happen,” Lee says.

Not Rising to the Challenge

So why aren’t more teachers and administrators in rural areas taking the lead in creating safer space for LGBT students in their schools? For some districts, it may be a lack of awareness, says Heather Rodriguez, program director for Triple Point, a youth group for LGBT teens in Walla Walla, Washington. While virtually all U.S. schools now trumpet anti-bullying policies, most fail to include language specific to sexual orientation and gender expression. And some educators don’t even acknowledge that anti-gay references qualify as harassment.

Other reasons for failing to protect LGBT kids can be tied even more directly to bigoted attitudes, Rodriguez notes. Some teachers are fearful of being ostracized by colleagues and harassed by parents. Many rural educators carry their own anti-gay attitudes into the school building. Korey Gaddis, now 21, recalls an assistant principal telling him to his face, “You shouldn’t be gay.”

Then there is the threat to job security. In some rural districts, even engaging the subject of homosexuality can threaten careers. “Administrators in our area fear parents lashing out, whether about sex education or creating a GSA [Gay-Straight Alliance],” Rodriguez says. “Teachers and school counselors fear for their jobs. Nobody wants to rock the boat.”

These are not phantom fears, as events in the small town of Grandfield, Oklahoma, revealed last year. As part of her ethics class, high school teacher Debra Taylor received her principal’s permission to feature The Laramie Project, the play and movie about the murder of gay college student Matthew Shepard. Her goal was to explore the roots of hate and intolerance. A few weeks later, the principal abruptly told Taylor to stop, which she did. But when she subsequently held a 20-minute class wrap-up on the material, the district superintendent suspended her for insubordination. Taylor resigned before she could be fired.

“I would be naïve to think what has happened to my students and me is an isolated incident,” Taylor later wrote in her blog. “Unfortunately, those in charge of the school just don’t get it. I know any gay student at Grandfield High School has been taught a dubious lesson. They have learned they better keep quiet until they are old enough to leave town.”

“We Can Be Better”

Many small-town LGBT teens have learned that lesson well: Endure lives in the closet until adulthood gives you the means to move to more accepting communities. A quarter of gay teens who come out get thrown out of their homes or run away. Others kill themselves. Studies have consistently shown that LGBT youth are at elevated risk for dropping out of school, substance abuse, homelessness, depression and suicide. The lack of support in rural communities only heightens these risks.

The attempted suicide of a former student motivated veteran visual arts teacher Allison Kleinstuber to take a leadership role in helping LGBT kids and their allies at Golden West High School. The school is located in Visalia, a small city set in the center of California’s rural Central Valley.

“There are few resources for LGBT youth here, and we don’t have an environment that makes it easy to come out,” Kleinstuber says, noting that the area has a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. “A lot of people here have a very literal way of looking at religious teachings.” While she embraces her faith-based belief that “Nothing else matters but love,” her friends and colleagues have made clear their condemnation of homosexuality as well as their disapproval of her decision to act as advisor for the school’s new GSA, launched last fall.

School administrators and GSA members are still working around their mutual distrust, Kleinstuber observes. And parents have protested when they discover that their children—whatever their sexual orientation—have attended club meetings. “But I think there’s a lot of staff, a lot of kids, who are glad [the GSA] is here,” she says.

A self-described “tough teacher,” Kleinstuber applies the same high standards to her school and district that she sets for students whose class work and behaviors do not meet her expectations. “We can be better,” she tells them. And she thinks teachers and administrators have an obligation to make schools safe places of learning for all kids, whatever their race, ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation or gender expression.

Heather Rodriguez hopes teachers and counselors would at least educate themselves about the means to help LGBT youth. “I want educators to know where their local resources are,” Rodriguez says. “Even if they’re not comfortable dealing with the issue of homosexuality themselves, they can at least know where these kids can go to get support.”

As part of in-school efforts, Mark Lee would also like to see more teachers in his area crack down on anti-gay speech in classrooms. He presses administrators to demonstrate leadership and courage to embrace student-empowered GSAs rather than stonewall their creation. He encourages teachers and counselors to post “Safe Zone” signs on classroom doors to send a clear signal to LGBT youth—and their tormentors—that gay students are not alone when running the gauntlet of hallways, bathrooms and locker rooms.

“I really think those signs make a difference,” Lee says. “They signal these kids that there are places they can go where they know they’re not crazy.”

Student Non-Discrimination Act

Federal non-discrimination laws specifically address discrimination based on characteristics that include race, color, sex, religion, disability and national origin. But they do not specify sexual orientation. This leaves LGBT students and their parents with few legal options when faced with the hostility and prejudice that are so common in public schools.

The Student Non-Discrimination Act (SNDA) would establish a comprehensive federal prohibition on discrimination in public schools based on actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity.

First introduced in January 2010, the bill is modeled after Title IX, which prohibits discrimination based on sex. If approved by Congress, the SNDA would help ensure that all students have access to public education in a safe environment that is free from discrimination and harassment.

For additional information and resources, see the Safe Schools Coalition. Also, check out Teaching Tolerance resources.