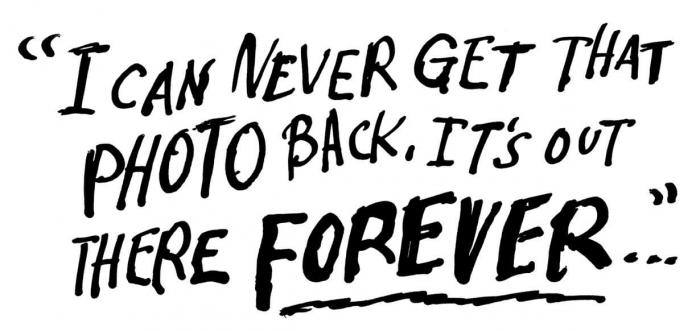

On September 7, 2012, 15-year-old Amanda Todd uploaded a video to YouTube. Using handwritten flashcards, she silently told her story. She had been coaxed into flashing a man on the Internet. He blackmailed her and then sent the images to her friends, family and peers, igniting a series of cyberbullying attacks. Struggling with depression, anxiety, cutting and thoughts of suicide, she changed schools, but the bullying only escalated.

On October 10, Amanda was found in her home. She had killed herself.

Research shows that sexual bullying starts in elementary school, usually in the form of verbal insults, typically by boys and directed toward girls. But sometimes girls are the instigators. Regardless of the source, this type of bullying is often referred to as “slut-shaming.”

“Slut-shaming is the shaming [or harassment] of a girl because she has casual sex or is perceived to have casual sex,” explains an 18-year-old female member of a Facebook group called Stop Slut-Shaming.

Slut-shaming isn’t new. But social media is, and it’s a powerful tool in the hands of teenagers who aren’t fully aware of the consequences of their online actions. The majority of bullying behavior now takes place through social media platforms—many of which are unfamiliar to educators.

Capturing the Moment: Webcamming, Sexting and Screen-Grabbing

Teenagers have become their own paparazzi. Four out of five teens have cellphone cameras. From selfies to food porn and photo-bombing, kids are constantly “capturing the moment.” They rarely seek permission from their subjects—making what were once private moments now very public.

Gone are the days when house rules could keep kids out of one another’s bedrooms. Now they are simply webcammed in without parental knowledge. Practically every computer has a camera and the ability to screen-grab, and services such as BlogTV, Tinychat, FaceTime, Hangouts and Skype allow kids to interact live with friends—and strangers.

When Amanda wrote on her YouTube flashcards, “I can never get that photo back. It’s out there forever …,” she was not alone in her despair. One in 10 junior high and high school students has had embarrassing or damaging photos taken of them without their permission. An equal number reported feeling “threatened, embarrassed, or uncomfortable” by a photo taken of them, specifically a photo taken with a cellphone camera. An MTV-AP study on digital abuse reports 39 percent of teenagers engage in sexting, including video, images and text. And one in five students has sent sexually suggestive or nude photos of themselves to others, reports the Cyber Research Bullying Center.

When Snapchat (an application through which users can send images, text or video that can ostensibly be seen only once before they “disappear”) came out, teen users flocked to the promise of consequence-free sharing of explicit images. The reality was less comforting: Snapchat images don’t actually disappear. After they are viewed and seemingly erased from the application, a media file remains, and it is simple for users to retrieve it.

The Social Media Underground

Some cyberbullying takes place out in the open, as in Amanda’s case. A Facebook page dedicated to shaming her was created, using an image captured without her permission and knowledge. It was shared with her community via email, creating a gang who then posted on her Facebook wall, texted her, emailed her and shamed her at school.

Slut-shaming isn’t always so easy to spot. Mainstream social media platforms (like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube) may be where cyberbullying starts, but the harassment often continues and worsens in more hidden online venues. Although Facebook is still rampant with bullying, its use is slowly decreasing due to its very public nature, explains a 14-year-old Connecticut girl who has admitted to sexual bullying and being bullied herself, “because kids are smart and know parents and college people see it.” Cyberbullying is sinking further below the surface as teens harness new technology and more creative methods. These stealthier attacks leave their targets mentally and emotionally taxed, carrying around a terrible secret, out of adult view.

Take, for instance, Twitter. Ask most adults what a “tweet” is, and they’ll probably be able to tell you. But what about a “subtweet”?

“A subtweet is a tweet about someone else on Twitter that doesn’t directly mention them,” explains Digital Trends writer Kate Knibbs. “Instead of being confrontational, subtweets are sneakier—they’re not the locker room brawls of Twitter; they’re the cruel lockerside whispers.” For example, instead of including @FakeStudent’s Twitter handle in a tweet about her, bullies might create a hashtag to represent her, refer to her through inference, use the hashtag #oomf (one of my friends or followers), or use initials that people inside their circles can identify easily but parents and schools cannot.

The Dangers of Anonymity

Nothing breeds irresponsible behavior like anonymity—and apps that promise just that are on the rise. Whisper, an app that allows users to anonymously post their feelings and thoughts via images with overlaid text, is becoming more popular with high school students. According to a Florida sheriff’s daily crime report, student use of the app “to post anonymous comments about one another, about relationships and about school” caused two counts of battery, an investigation into cyberstalking and an incident of disorderly conduct, all in the span of one day.

A similar application, slowly gaining popularity, is GO HD. Users can post images, video and text anonymously and “pin” them on a location. Posts are available to the public via map browsing or search. Images are available for the public to see and share via Facebook and Twitter without the fingerprints of the original poster. Although GO isn’t marketing its app as a secret-sharing program, users are encouraged to “broadcast videos, photos or text from your GPS location instantly” and “view realtime streams of what’s happening anywhere in the world.”

Advertised as applications for pranksters, professionals and people doing business online, apps like SpoofCard, Hushed and Burner allow users to disguise themselves and send texts or make phone calls anonymously. Burner, an application for disposable or temporary phone numbers, allows users to purchase an anonymous number for $1.99. It’s referred to as a “privacy layer.” These layers, depending on the app, can also include voice changers, background noise additions, the option to record calls and the ability for others to listen in.

Acting Fast

When the world hears about gender-based bullying, it’s because the silent abuse has finally boiled over. But slut-shaming takes place every day. It starts small and simmers beneath the surface for months or even years.

There is no easy cure for cyberbullying. Much of it happens off campus. It’s hard to define—and harder to locate. What educators can do is create an atmosphere in which respect is valued. They can teach their students about digital citizenship and the real-world impact of online actions. But first and foremost, educators must commit to staying abreast of an ever-changing digital landscape.

Students may be savvy social media users, but educators can learn to speak their online language. Doing so is the first step toward being able to respond quickly when the message is “help.”

Learn the Language

a/s/l/p age/sex/location/pic

BOM bitch-of-mine

bop to have oral sex

bopper someone who gives oral sex

CD9 code 9, parents around

FYEO for-your-eyes-only

honeydip main girl on the side

HSWM have-sex-with-me

jumpoff a girl used strictly for sex

NIFOC naked-in-front-of-computer

OH overheard the following information

PAW parents-are-watching

POS parent-over-shoulder

sugarpic a suggestive or explicit photograph

THOT that-hoe-over-there