“Half the curriculum walks in the door when the students do.”

—Emily Style

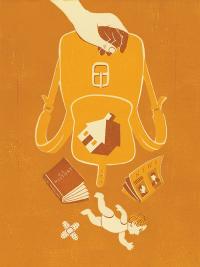

Those who study the dynamics of race, bias and privilege have likely read—or at least heard of—“White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” Excerpted from McIntosh’s longer piece on white and male privilege, the article has been translated into multiple languages and is read and quoted by multicultural scholars and educators all over the world. But while many know the metaphor (“white privilege is like an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions …”) far fewer know the author, feminist and anti-racist educational scholar Peggy McIntosh—or her method of Serial Testimony.

By all conventional measures, Peggy McIntosh was a model of success long before she wrote “The Invisible Knapsack.” From her early school days she moved easily in academic circles, eventually earning multiple degrees from elite institutions. But despite all her accomplishments, McIntosh—a career educator—says her definition of success changed radically later in life when she began to see the education system through lenses of color and gender privilege. What she saw disturbed her.

“I began to see systems at work—in the society and in my own previous education—that prevented me from thinking about most of the world,” says McIntosh. “I realized that this whole system of education had put me in a position of trying to climb up to the so-called top lest I fall toward the ‘bottom’… I was taught to look down on almost everybody.”

McIntosh underwent a period of self-reflection that led her to change her teaching. She cut back on lecturing. She stopped favoring those who always raised their hands. She had her students teach entire classes on topics they selected themselves.

“When I first saw white privilege as a system of unearned advantage … that completely transformed my teaching and my sense of who counts. … I began to teach in such a way that all the children were included, I expanded my curricular choices … [and] I began to think about teaching teachers.”

Over time, McIntosh realized that her classroom innovations were directly linked to the process of revisiting her own story as a white woman in the academic world. She began building reflection, storytelling and personal history into her work with adults as well as children, first at the Rocky Mountain Women’s Institute, which she cofounded, and then at the Center for Research on Women at Wellesley College (now the Wellesley Centers for Women). During this time she developed a pedagogical approach called Serial Testimony, a facilitation method that asks participants to respond briefly to a question or prompt by drawing on their life experiences.

“In Serial Testimony, participants, whether they are adults or schoolchildren, speak in turn around a circle or around a classroom for a limited time without referring to what others have said,” McIntosh says. “They speak from experience—not from opinion—and hearing each other, they also learn more about themselves.”

The gift of Serial Testimony, says McIntosh, is that it privileges the living knowledge of every person in the room. Topics vary greatly but often focus on matters of identity and bias; for example, participants may be asked to describe experiences of having unearned advantage or disadvantage with regard to class, ethnicity, religion, gender or race. Sessions usually begin with an explanation that the individual testimonies will be uninterrupted. The leader uses a timer to ensure equitable sharing. The group neither responds to nor debriefs the testimonies, preventing other points of view from obscuring the personal narratives. Although group members may revisit stories or themes during later discussions, no one is questioned or challenged about their experiences while sharing.

To expand the reach of Serial Testimony (and other teaching strategies that value student experience), McIntosh partnered with other radical educators to launch an in-depth professional development project called Seeking Educational Equity & Diversity, the National SEED Project on Inclusive Curriculum (see sidebar). After participating in the intensive residential New Leaders’ Week, SEED leaders spend a year in their own schools discussing curricular expansion and inclusive teaching methods with colleagues during monthly school-based seminars.

The point is not to begin with abstract frameworks ... but to have students tell their stories of daily life, what happens to them. ... A student who is in a class like that wants to be in school. Because he or she is taken seriously.

Chris Avery is both a SEED seminar facilitator and a summer SEED staff member who uses Serial Testimony with his fellow teachers and his middle school students. Avery notes that Serial Testimony can effectively deepen both curricular engagement and participant investment in subjects ranging from literature to history, from current events to psychology. Sometimes he begins with the curricular material and asks students to react through Serial Testimony; at other times he begins with a question designed to generate topical discussion prior to a reading or lecture as a way to set the stage. For example, Avery has used Serial Testimony to open a history discussion about Woodrow Wilson’s ideological vision for the Treaty of Versailles by asking students to talk about a time when a plan or dream of theirs was realized or not realized.

“[The Treaty] became more than some incident that happened in 1919, when it is 2013 now,” Avery says. “When [students] are allowed to be the experts … it’s amazing how much more they’re willing to learn. … When they understand that their thoughts are valued because they are their thoughts and not because they said the smartest thing or the most incredible thing … you start to get more authentic thought.”

This authentic thought, says McIntosh, allows students (and teachers) to arrive at their own conclusions about how their lives connect to the world around them. Rather than being lectured about power dynamics, the dynamics become visible to students when reflecting on their own and each other’s stories—just as they became visible to McIntosh almost 40 years ago.

“If you see part of your task as a teacher is to elicit what students already know, you needn’t start with words like privilege,” McIntosh explains. “The point is not to begin with abstract frameworks … but to have students tell their stories of daily life, what happens to them. … The teacher needs to support them: ‘In Serial Testimony, you are talking about your knowledge. And the society needs your knowledge.’ … A student who is in a class like that wants to be in school. Because he or she is taken seriously.”

McIntosh asserts that traditional top-down educational models do not take students seriously and—as a consequence—isolate them, particularly students of color, from their own bases of knowledge. Serial Testimony is transformative in that it engages and honors young people, balancing—in the words of SEED cofounder Emily Style— “the scholarship on the shelves with the scholarship in the selves.”

“It is clear to me,” says McIntosh, “that students are not encouraged to study their own experience of school. You can get a whole Ph.D. in education without reading a single thing said by a student about their experience of being in school. They are authorities on schooling, but nobody asks them.”

New Jersey-based teacher Peter Horn participated in a SEED seminar at his school and worked closely with Style. Horn notes that Serial Testimony not only teaches him more about his students and their expertise, it also enriches his own teaching experience and engagement with the curriculum.

“Hamlet … may not be the thing that [they]’re most comfortable talking about,” Horn says. “[But] understanding what the students have to offer by remembering they are half the curriculum … that’s how Hamlet’s going to change even if I teach it for 17 years. … If I hear about where it affects the students and think about the extent to which we’ve all been oppressed by family sometimes like Ophelia is, or a way that you’ve oppressed somebody else … it makes the conversations more interesting, it makes the connections better. It changes how lively and vital the discussion feels. So if they’re willing to put it out there, they’ve got an area of expertise. And if that’s accepted, it can really change the way they feel about sharing.”

Now in its 28th year, the SEED New Leaders’ Week is a seven-day professional development training during which teachers are immersed in methods and processes designed to create “gender fair, multiculturally equitable, and globally informed education.” Participants explore and share their own narratives and learn to apply what they learn about themselves and each other to their own teaching and how to help others do the same.

SEED Leaders bring methods like Serial Testimony back to their own schools, where they lead monthly seminars, allowing more teachers and—ultimately—many more students to benefit from a pedagogical model designed to honor the unique knowledge and capability inherent in each learner. Schools commit to supporting the seminars by providing food, space and materials.

Those trained at SEED form an international network of educators who maintain contact and support each other’s successes as leaders in their schools and innovators in their classrooms. Regional leaders meet face-to-face; the program also supports an active online community through Facebook and the SEED website.

SEED New Leaders’ Week is held twice every summer in San Anselmo, Calif. The National SEED Project on Inclusive Curriculum is directed by McIntosh and fellow pioneer educators Style, Emmy Howe and Brenda Flywithhawks. Associate directors are Jondou Chase Chen and Gail Cruise-Roberson.