In November 2005, Alejandra Lalama was feeling hopeful about college. The New Jersey teenager had been accepted at Full Sail Real World Education (now Full Sail University), a for-profit school in Florida specializing in music, video and film production. It seemed she was on the path toward her dream career as an audio engineer.

“The school had the best of the best in hardware, software, stages,” Lalama says. “I guess for a 17-year-old, it looked exciting.” A Full Sail financial-aid counselor laid out a package of government and private loans. After listening to her daughter’s pleas, Lalama’s mother—a single parent and a teacher—put down the $650 application fee and deposit.

Fast-forward eight years: Lalama has her degree, but she now pays $758.51 a month toward her student loans. Due to compounding interest, only $4,360.14 of the $32,000 she has paid so far has gone toward her principal balance. She still owes more than $65,000 overall.

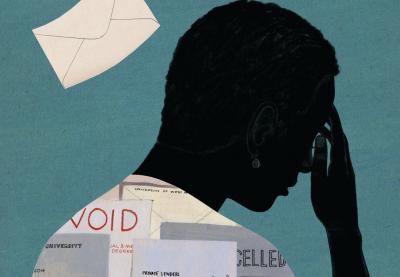

For middle- and low-income students like Lalama, the path to higher education has become fraught with financial traps. Whether these students attend for-profit schools like Full Sail, private colleges and universities or public institutions, shifts in financial-aid policies and questionable lending practices have put a growing number of idealistic students and their families in long-term financial peril. Children of immigrants, students of color and first-generation college attenders are particularly vulnerable.

The Inflation of Higher Education

For the last 35 years, the costs of postsecondary education have been rising at unprecedented rates. According to Bloomberg and the U.S. Department of Labor, college tuition and fees have ballooned 1,120 percent since 1978—an inflation rate that is four times the consumer price index. A year of college tuition for an out-of-state student currently averages about $22,000 a year at four-year public universities.

Policy analysts, including Rachel Fishman at the New America Foundation, trace the skyrocketing costs of the last generation to two main variables: (1) Many schools have taken on heavy debt of their own to upgrade their facilities and better compete for faculty and students; (2) states have slashed public contributions to higher education due to budget crises.

“Many of these financial and educational institutions do not have student outcomes at the heart of their mission,” says Fishman. “Institutions have been shifting the costs to students through higher tuitions and fees.”

Some for-profit institutions capitalize on student aspirations by enrolling students with little regard to their academic or financial qualifications. And some specifically target students of color using slick advertising campaigns that emphasize racial diversity and hopes for a brighter future via education.

What these schools don’t highlight are average graduation rates of 42 percent after six years, according to National Center for Education statistics, significantly lower than the average for private nonprofit colleges (65 percent) and public four-year institutions (57 percent). What might be worse than leaving college without a degree? Not having a degree and being on the hook for tens of thousands of dollars.

For many lower-income students, a shift in financial-aid practices has also widened the money gap they must cross to complete a degree. In order to boost college rankings, schools have been shifting financial-aid dollars from “need-based” to “merit-based” aid in order to lure top-performing students. A study by the New America Foundation reports that, at almost two-thirds of private colleges, students from households earning less than $30,000 annually pay more than $15,000 per school year.

“Colleges are always saying how committed they are to admitting low-income students,” Stephen Burd, the report’s author, told Bloomberg BusinessWeek. “This data shows … the pursuit of prestige and revenue has led them to focus more on high-income students.”

These shifting priorities, policies and practices are pushing students—particularly students of color—into the clutches of private lenders.

Shining Light on College Costs

Some colleges have become masterful at hiding fees and other costs while disguising unsubsidized loan packages as financial aid. A bipartisan Senate bill, the Understanding the True Cost of College Act, S. 1156, hopes to change that. Introduced by Minnesota Senator Al Franken in 2012 and 2013, the bill would require American colleges to issue a standardized financial-aid award letter with clearly itemized information regarding expected costs, grants, scholarships and loans.

Stated the bill’s co-sponsor Tom Harkin: “This bill will remove some of the mystery and guesswork for students and families as they navigate the higher-education marketplace and empower them to make fully informed decisions about where to attend.”

Use this new tool from the U.S. Department of Education to help students calculate long-term lending costs.

Debt Inequity

This past year, student debt exceeded $1.1 trillion—blowing past the country’s total credit card debt. This burden affects African-American and Latino students disproportionately, according to a report by the Center for American Progress and Campus Progress. While 64 percent of white students graduate with debt, that figure is 67 percent for Latino and 81 percent for African-American students.

Twenty-seven percent of black students graduate with more than $30,500 in debt compared to 16 percent of their white peers. Debt burdens also drive unequal drop-out rates: 69 percent of African Americans who leave school without a diploma cite their debt burden as a major factor in their decision, compared to 43 percent of white undergraduates who drop out.

For families and students committed to getting a degree at any cost, however, determination can trump prudence. Parent PLUS loans, which until recently were doled out liberally without considering borrowers’ ability to repay, are notorious money traps. “[Parents] want what’s best for their child,” says Dr. Shelby Wyatt, head of guidance counseling at Chicago’s Kenwood Academy High School. “But they may not have the money for it. All it may take is one missed paycheck and they spiral into economic trouble.”

Loan defaults, especially on private loans, trigger punitive fees and interest-rate penalties that can turn a five-figure financial hazard into a six-figure nightmare. In addition, changes in bankruptcy laws have made college debt nearly impossible to discharge, regardless of financial hardship or even the death of the student. In practice, banks and schools have shifted nearly all financial risk to borrowers, creating a debt trap that can snare both unlucky students and their family members.

Assume Nothing

How can high school counselors and educators help their students sidestep these traps? By sharing critical knowledge with those who need it most—and sharing it early. Beginning in ninth grade, Kenwood students and their families visit colleges, meet with panels of college representatives and attend financial-aid workshops.

“You can’t wait until senior year to get young people to start thinking about these things,” Wyatt says. After students identify their career interests, their next steps include identifying schools—at least two or three—with good programs in their areas of interest.

“We also have them answer, ‘How am I going to pay for this?’” Wyatt says. “We’re not trying to scare people away from loans. … But we want them to have the knowledge and tools to make an informed decision.”

Wyatt, who was named a finalist for the American School Counselor Association’s 2013 School Counselor of the Year award, assumes nothing about students’ prior knowledge when it comes to college searches, financial aid or college culture. While one family may have a firm grasp on these variables, another may lack the financial literacy to spot a predatory loan before signing the papers.

A Dream Deferred

Today, Lalama is back living with her mother. She works for an Internet service provider so she can pay back her loans. “Pretty much my entire paycheck goes to that,” she says.

She despairs of ever producing beautiful music from a studio booth. “I regret going to Full Sail,” she says, and she wishes she’d received more support from her high school counselor. She also contends that the financial-aid representative at Full Sail glossed over the actual sticker price of her degree, a price difficult to calculate due to highly variable interest rates.

Lalama now believes she would have been much better off learning her craft through internships and sticking with a cheaper school closer to home. “I would have saved a lot of money,” she says. And maybe her dream career, too.

Dollars and Sense

Counselors are in a position to guide students through an increasingly treacherous financial-aid system. Here are some tips.

How many schools should students apply to?

At least two or three, Dr. Shelby Wyatt (head of guidance counseling at Chicago’s Kenwood Academy) suggests. Students can request a need-based waiver if the application fee is scaring them away from applying to more than one school.

What if students are unsure what they want to study or pursue as a career?

Encourage students who are uncertain of their direction to consider making a deliberate plan to explore various options, such as a year of work, a technical program, an internship or a volunteer gig in an area of interest.

How can educators help students plan their next steps?

Wyatt suggests counselors and mentors encourage students to define areas of interest, then explore educational paths that lead there. That path may be a four-year college; vocational-technical schools or apprenticeship programs, however, may offer the best value.

How much school debt is too much?

A useful rule of thumb for students paying most of their own way: School debt should not exceed the average starting income of a likely entry-level position, according to Mark Kantrowitz, publisher of FinAid.org.

Besides loans, what other resources can help pay for school?

Family contributions, grants, scholarships, public-service loan-forgiveness programs and military aid can all reduce the amount a student needs to borrow.