One month after their city became a hashtag, students at Murray High School in Charlottesville, Virginia, are building birdhouses.

For some students, it is the first time they’ve built something with their hands. The process requires care—and time. The students all start with the same raw materials, but each shelter is unique; different birds require different kinds of habitats to thrive.

The birdhouses bear messages intended for the individuals who sought to bring hate into their community. Painted on one: “Humans are born to love.”

The naked display of hatred in Charlottesville sent shock waves across the United States. Educators scoured the web for resources to answer the question burning in torch-borne flames: How do we address this within the classroom? How do we address this within ourselves?

It just so happened that one of the school districts most ready to respond to the crisis was at its epicenter.

On Saturday, August 12, the rally marched past the offices of Albemarle County Public Schools (ACPS) administrators. The offices were empty, but the staff still felt the presence of the marchers.

“There were tears in my eyes,” says Superintendent Pamela Moran, recalling seeing her building on television. “It was almost as if they were insulting the work of the people who are in this community trying to do the very best that we can do for our kids.”

That work has been a decade in the making—the result of a districtwide commitment to culturally responsive education led by the Office of Community Engagement and its executive director, Bernard Hairston. Although shaken by the visceral images on the news, ACPS officials found strength in this foundation.

School leaders exchanged phone calls. Long-established plans went into motion.

According to the district’s strategic communications officer, Phil Giaramita, this made all the difference.

“There was a value in having these things in place around the issues of diversity and openness and responsiveness,” Giaramita says. “And those things, in a crisis situation, really provided a good foundation so we didn’t need to do anything special.”

That’s because, in Albemarle County, Hairston and others know that building a shelter for all students requires care—and time. The raw materials must be malleable, because the mission calls for it: Different students require different resources to thrive.

“If you don’t have that kind of mindset in place, frankly, there aren’t enough resources anywhere that you can go out and find when the situation is blowing up,” says Student Services Officer Nicholas King. “It’s long-term work.”

And it’s replicable.

The House That Care Built

The work, according to Hairston, began in the early 2000s with an emphasis on Glenn Singleton’s call for courageous conversations about race. But in 2008, the elimination of a district-level position focused on equity and diversity catalyzed a broader movement centered on culturally responsive teaching. Now, instead of one person tasked with promoting equity, the responsibility is shared across a team of trained educators and bolstered by professional development and collaborative meetings focused on best practices.

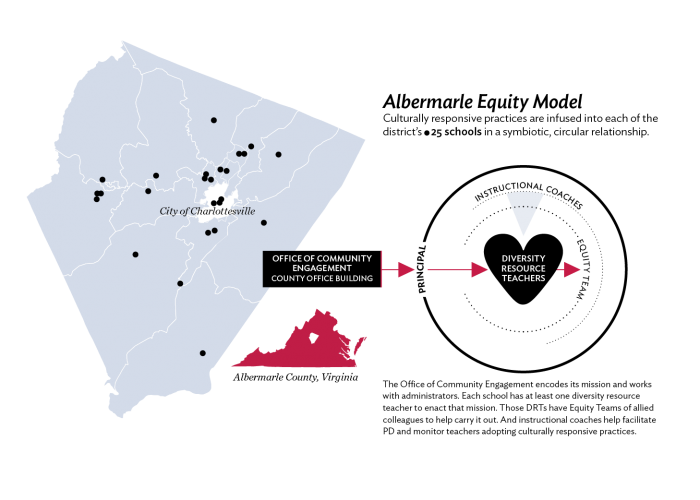

Each of the district’s 25 schools employs one or more diversity resource teachers (DRTs), and—since the 2015-16 school year—equity teams of various sizes surround those teachers. These teachers meet monthly and evaluate their efficacy at the end of each year. DRTs create workshops and provide supports for teachers in their respective buildings. These supports are tailored to the needs of the students in their schools. The district incentivizes teachers to take a deeper dive into culturally responsive pedagogy by offering a rigorous, one-of-a-kind certification program.

“Part of a culturally responsive teaching model is to make sure that people are able to talk about these issues,” Hairston explains. “And now we’re coming back to those courageous conversations.”

Knowing their students and how to talk to them served teachers like Murray High School’s Catherine Glover well. Her students experienced August 12 in a variety of ways. Some were shielded, taken out of town. Others attended the rally. Most students could put names to faces on the news. For one boy, Marcus Martin is not just the man famously photographed, midair, after saving his fiancée from the oncoming car. He’s “the man who works with Dad.”

Murray High is Albemarle County’s nontraditional school. An underlying mission informs the culture there. As Moran puts it, “if we really want to effect change and positivism in our communities … we really have to learn how to shift power from the teacher to the kid.”

At Murray High, unique identities and needs are honored. Conflicts are handled through mediation. The birdhouses now hanging in the hallway are a metaphor for the building around them, itself a microcosm of the district’s goals.

And so—in a nontraditional classroom featuring armchairs and dim lighting—students are talking about what happened on August 12 and the ways to cure what ails a divided United States.

The students start to talk about solutions: modeling behavior and having empathy for how environmental factors can shape people’s perspectives. And you can see the rewards of culturally responsive teaching work in real time.

“Stop hiding from uncomfortable conversations,” one young woman offers. “We’re all one race, the human race; that’s lovely. But we have to address times that everybody isn’t true to that. We can’t let it slip by.”

Another student says, meekly, “I wonder if it will ever go back to normal.”

His peer challenges him. “But what is normal?”

When Nicholas King held a virtual meeting with principals on August 18, he understood that the events of the previous weekend would have a lasting effect on the way students interacted with leadership, activism and politics. School leaders embraced the opportunity to talk about their fears and how to address them.

“We’ve not been one of those places that has had our head in the sand,” King says.

Over the 10 years of equity initiatives, ACPS has responded to many challenges and changes, both in its population and in the surrounding community. Today, students from 95 different countries of origin attend school in the district. The enrollment of English language learners has increased tenfold as compared to student population growth. The district is recognized for its high graduation and low dropout rates, and for its innovative programming. But it keeps going. As Principal Lisa Molinaro says of Woodbrook Elementary—where the majority of students are children of color and nearly half experience economic disadvantage—“I believe that if we can do it here, we will send a message everywhere else to say it can be done.”

The Three Characteristics of Culturally Responsive Teaching

at Albemarle County Public Schools

- Communicating and practicing high expectations to empower all students, with an awareness of differing cultural lenses.

- Acknowledging and incorporating the relevance of cultural heritages of students into instructional strategies and design.

- Building positive relationships with and among students in the context of culture and their communities.

Support at Every Level

Years of advocacy and conversations have created a unified front in Albemarle County, and the ramifications are huge. Equity is the lens through which all decisions are made.

Most importantly, classroom and school leaders engaging in equity work receive support instead of pushback.

“You can’t both hold the power close and also give it away,” Moran says. “It’s the people who try to consolidate power that end up probably having the least influence.”

Instead, district leaders like Hairston, Moran and Deputy Superintendent Matt Haas use their positions to codify the mission of equity into the policies (and budgets) of Albemarle County Schools. The district is even working to make sure all policies pass an equity test.

“It’s kind of a point of departure,” Haas explains. “If you don’t address what your vision is through policy, it is kind of a Wild West where people do whatever they want.”

This approach has helped reduce suspensions across the district and increased the number of social emotional learning specialists in schools with the highest populations of marginalized students. But perhaps the most influential district-level mission is the one that allows teachers to lead the way: Hairston’s credentialing program for culturally responsive teaching.

“When you push something out like culturally responsive teaching, that’s a carrot,” Haas explains. “It’s a program that you can get involved in, feel passionate about.”

The program isn’t easy. Only eight teachers, thus far, have completed the certification. But the positive results are already obvious, as evidenced by the leadership by teachers like Lars Holmstrom, Leslie Wills-Taylor, Brandon Readus, Monica Laux and others; they are spreading the word—by design.

“Everybody’s a teacher and everybody’s a learner,” Moran says. “How [can] the work that Dr. Hairston has put in place with a team of people ... start to go viral?”

That “ever-expanding group” was key to many teachers finding their way forward when #Charlottesville went viral.

“There was an open wound in our town,” Wills-Taylor says. “If I go to the downtown mall, it feels different to me.”

Wills-Taylor spent much of that weekend finding solace in her colleagues, knowing they shared a commitment to providing students a safe, but engaged, space.

“I had a refuge,” she says. “I had people that I could call and reach out to and figure out how we could use our pedagogy, how we could use our discourse among teachers, to begin to heal.”

So when Wills-Taylor and Holmstrom led professional development sessions the following week, they gave their fellow educators a chance to unpack.

“Before we teach, we reflect,” Wills-Taylor says.

Confronting the fear of addressing August 12 in class helped teachers repackage their own reactions and find a comfort zone—because they had to.“As tragic as this event was,” says Wills-Taylor, “I’m incredibly enthused and excited about what our division has in place to press that ‘activate’ button. “The tools are here.”

Responding to Hate and Bias

If a hateful event happened in your school or community, would you be ready? Create a plan with our resource, Responding to Hate and Bias at School.

Flattening the Hierarchy

The Office of Community Engagement offers resources to district teachers, including the work of Zaretta Hammond, Teaching Tolerance, EduColor and more.

But Hairston’s work has gone far beyond dropping resources into at-risk environments. A nonprofit he founded helps recruit young teachers of color to Albemarle County, and he offers learning and leadership opportunities to young, culturally responsive teachers so they can more quickly become recognized in the district.

“I think one of the most important things that I really believe in is, how do you flatten the hierarchy?” Moran says.

Even an abridged tour of Albemarle County’s schools reveals a company of principals and teachers recruited to enact a districtwide commitment to equity and to shape and evolve what that commitment looks like.

“I feel confident that I can be put on record to say, yes, that does make my work easier,” says Lisa Molinaro.

And Molinaro’s work isn’t easy. When she became Woodbrook’s principal in 2010, Molinaro encountered a school with kids of color sitting in the hallways and a full-size trailer serving as a suspension center out back. A dozen or more kids spent their entire days there, silent.

“I had arrived to a school that really had its culture stripped,” Molinaro says.

Seven years and an almost entirely different staff later, Woodbrook is barely recognizable. There is no suspension center. There is no classroom with traditional, industrial seating. Across the building, staff share a collective mission to serve a diverse student population responsively.

“It’s no longer a single voice,” Molinaro says of the culturally responsive teaching effort. “I have, I don’t know, 18 classroom teachers, a staff of roughly 45 and our diversity resource team is 20 people. And they’re there because they want to be there.”

Before moving into an administrative role, Wills-Taylor taught at Woodbrook. After the events of August 12, she wonders how the school and district might have responded without the current support system in place.

“I honestly can’t imagine it,” she says, explaining the domino effect that spreads best practices from professional development to diversity resource teachers to instructional coaches to schools across the district.

That network of educators empowered Catherine Glover to respond to the events of August 12 with urgency.“I felt more strongly than ever that … the fact that we are a community is going to sustain us,” Glover says.

Read more about Lisa Molinaro’s journey to Woodbrook Elementary School.

Looking Forward

At ACPS, they now call the “Unite the Right” rally “what happened on August 12”—an attempt to disempower white supremacists and nationalists by omission.

“When people hear the term Charlottesville, their immediate association with that is intolerance and divisiveness,” Giaramita says. “It’s not representative of our school division. And we don’t want to be defined by that.”

The work of educators in Charlottesville is helping the next generation define their values and the types of schools they want to attend. When they go out into the community, when they listen and empower diverse voices, when they emphasize the importance of context and empathy—it trickles down.

And so the students at Murray High have ideas as to how they can halt hate before it marches again.

“Taking ownership of your community,” one girl says.

“Care,” another boy adds. “Just do small things. Make sure people are cared for.”

Different students have different ideas about how to inoculate their community against hate. But outside in the hallway, the birdhouses communicate a common message: Hate does not belong in Murray High or in ACPS or in Charlottesville—because humans were born to love.

Collins is the senior writer for Teaching Tolerance.

After August 12 …

Albemarle County Public Schools was ready because they had response plans in place. This timeline summarizes the actions district leaders took in the days immediately following the deadly “Unite the Right” rally.

August 14

ACPS Superintendent Pamela Moran and Charlottesville City Schools Superintendent Rosa Atkins release a joint statement, declaring, “Our schools are where we make acquaintance with civic responsibility.”

August 15

Instructional coach Lars Holmstrom and TT Award Winner Leslie Wills-Taylor lead professional development sessions, helping teachers in the district to unpack the events of Charlottesville, then bring that conversation into their classrooms.

August 17

Bernard Hairston, ACPS executive director of community engagement, sends resources to his colleagues. He reiterates the focus on “aligning classroom activities with our core values, excellence, young people, respect and community as well as the benefits that come from culturally responsive teaching strategies.”

August 18

Nicholas King, ACPS student services officer, holds a virtual meeting with all district principals stressing how staff should respond to personal and student needs after August 12. “It is our responsibility to respond to student needs in a way that is measured, supportive and non-judgmental,” he says.