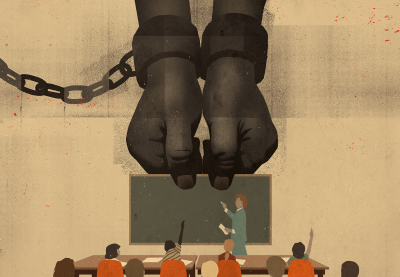

A terrible legacy of slavery and white supremacy undeniably influences life in the United States today. It is present in the U.S. system of mass incarceration, in police violence against black citizens, and in white society’s acceptance of poverty and poor educational opportunities for people of color. Learning about this country’s history of slavery and white supremacy is essential if we are ever to bridge the racial differences that continue to divide our nation.

Unfortunately, even as more and more teachers rise to the challenge of teaching about racism and racial justice, many struggle to teach effectively and responsively about slavery—the institution that poured racism into our national foundation. The subject material is undeniably complex and difficult; when we talk about slavery, we are talking about hundreds of years of institutionalized violence against millions of people. Their descendants—and those of the people who benefited from their forced labor—sit in our classrooms. And even though educators may strive for robust conversations about this topic, they are poorly served by state standards and frameworks, popular textbooks and their own history instruction. Compounding these factors is the reality that there is no consensus among experts on how to teach about slavery, plenty of questionable lessons online, and only a patchwork of solid advice offered by interpretive centers, museums and professional organizations.

Teaching Hard History

How can we fill this void? Teaching Tolerance recently conducted a review of available materials and asked thousands of teachers, students and researchers to tell us what they knew and what they needed to know about this critical topic. Based on this research, we developed a collection of materials titled Teaching Hard History: American Slavery. The collection features a library of texts, a set of inquiry design models and a podcast, all focused on best practices for effective and responsive teaching about slavery and white supremacy, and all vetted by an advisory board of leading scholars in the field. The materials hinge on an original framework for teaching about slavery and white supremacy—the first of its kind—that we hope will influence textbook publishers, state standards and anyone who writes or teaches about this history.

Teachers Talk

Meet four secondary educators whose teaching about slavery reflects the principles of Teaching Hard History: Laura Baines-Walsh of Brookline, Massachusetts; Jackie Katz of Wellesley, Massachusetts; Ryan New of Danville, Kentucky; and Kevin Toro of Arlington, Massachusetts.

We assembled these innovative educators to discuss how they teach about slavery with their predominantly white students. (As part of the Teaching Hard History initiative, we’ll be publishing a series of similar discussions with teachers who teach predominantly African-American students and teachers who teach in racially diverse classrooms.)

As you’ve gained experience as an educator, how has your approach to teaching about slavery changed?

Ryan: I’ve found that using sources, especially with an inquiry, forces students to have to figure things out for themselves. They have to deal with the fact that the source says this thing and there’s nobody else telling them what to think. I was finding that students had a hard time distinguishing between my thoughts on something and what the history was. And so by pulling back, becoming much more of a facilitator, and allowing the sources to speak for themselves. I can then be a person who’s going to prod them with questions or introduce new sources that will challenge their points of view.

Kevin: Getting a clear and precise history I think is so important to teaching this. We teach the economic reasons for slavery when we start out, and the reason why it started being this massive agricultural need and how that compares with a sort of narrative going out now about workers coming over to this country. We talk about all those things so that my students feel prepared to discuss this, I think as all of our students want to, as historians at the end of the day.

Jackie: A huge shift for me has been shifting from teaching slavery as victimization to agency and trying to find ways to incorporate ways that enslaved people tried to change their own situation, so that I wasn’t just presenting negative stories where they’re just the victims all the time. [Without that shift] it becomes problematic; it almost seems like, “Well then it’s white people’s jobs to save black people. Because they’re the victim.”

Can you describe one of the most challenging moments you’ve had while teaching about slavery?

Jackie: A challenging moment that comes up frequently is when students say, “Oh, well it doesn’t sound that bad.” Because I think the double-edged sword of teaching about agency is all of a sudden, kids are like, “Oh, well then they can run away.” Or, “Oh, they can collect coins.” Or, “Oh, they sing songs, so everything’s fine.” I have kids all the time who say things about how, “Oh, well this wasn’t so bad. See how Douglass was able to get away.”

So I think trying to predict how kids are going to respond to the primary and secondary sources and be able to have enough strategies that you can redirect them toward what was a horrible institution is really important.

Laura: One of the things that keeps coming up is this idea of, “This is so awful, it can’t possibly have happened. Why didn’t they just realize this was wrong and stop?” Or, they want there to be the good master. “Was Jefferson nice to his slaves? What about Washington?” Like they’re looking for some sort of good guy in this. And trying to find a way to talk to them in a developmentally appropriate way, so we’re not overwhelming them, but also bringing them to the awful truth that, even if a master wasn’t whipping their slave, they are depriving them of bodily autonomy. And there is not a kind way to do that. So bringing them to that is a very difficult thing, while also, like Jackie, looking for places of agency. Slaves were more than just property. They were wives and husbands and children, Christians and Muslims. And so trying to get that wide variety of slave experience.

What you have noticed that your African-American students need from you? And, for the white teachers in the discussion, do you feel like that’s different for you as a white teacher?

Ryan: Because we have such a large white population and such a small black population, oftentimes I have one or maybe two black students in my class. There’s always a difficult moment where I have to pull the student aside and be like, “Look. We’re going to be talking about some issues and everybody’s going to look to you, and you don’t have to speak on behalf of everybody else.” That’s always an issue. … So the biggest, biggest issue for me is figuring out how to disrupt the narrative in a way that’s effective, but also safe for all of the students.

Jackie: My mom’s from the Philippines. I identify to my students so that they know where I’m coming from and where my perspectives lie when I start off the year.

I’ve made mistakes where I’ve put feelings on to [students of color]. Like I’ve said, “You might be uncomfortable because we’re going to be learning about slavery,” instead of just posing more open-ended questions, like, “Do you have any concerns as we approach this unit? Are there things you might be worried about?” Students need to have a lot of space to have so many different reactions. And that they need their teachers to just be accepting of any reaction that they have.

Kevin: It’s super interesting because I was that kid for a while, sitting in class, and now I’m obviously a teacher of color.

[I]n Arlington we have a lot of white students. A majority, by far. But I have had students of color in my room while I’m teaching these subjects. And it hasn’t come up as a problem to me so far, but … it may be because I am the black teacher in the room and they’re looking to me for that, instead of the students themselves.

I also preface these standards, when we have discussions, speaking from the I, not speaking for everyone. I do preface [with] a lot of my own personal troubles with race as I’ve gone through my life, so we do talk about these sometimes-awkward moments when I was asked to talk or speak for all black people or speak for all Hispanics.

Get drenched in the content because, once you’re in it, it is so clear how so many of the problems that we face in the United States stem from our founding period as a slave nation.

What groundwork do you lay before broaching this topic with students?

Ryan: I show them all these beautiful cities, and I sa[y], “Tell me the name of this city and if you can’t get the name of the city, maybe where it’s from, maybe a continent or something like that.” And every single one of [the cities], of course, is in Africa. And no student in the 20 students that I have, none of them identified the continent of Africa for any of the cities. And we had a conversation about this. And I think that you’re never going to be able to talk about slavery in a very meaningful way if people don’t see Africans as people first, and that they were just as equally capable in every single way.

Jackie: I’d say some of that groundwork happens with just talking about issues of power and privilege and equity and hierarchy with things that are super safe and innocuous. I talk initially about how hierarchies were set up in the colonies. Because kids don’t have a lot invested in that. But if they can understand that those hierarchies existed early on, if you start with stuff that’s not heavy, it takes the defensiveness away from kids. When you get to stuff that’s like, “This is a legacy that you are living in,” it feels a little safer than if you just start with, “You live in a racist country, it’s been racist since its founding.”

Kevin: By the time we talk about [slavery] in my class, they’ve gone through the ideas of inequity, inequality, and the fact of the matter is, even though they know that people will use other people, the greed, all these bad things that people do throughout history that we’re all so well acquainted with, so that when the time comes to get to slavery, and we’re talking about how that leads up to civil rights, they are equipped to talk about how someone could feel like they own someone else and then breed a certain race for agricultural means and profit off of that and really stick to that.

Laura: My groundwork begins in the summer, with their summer reading book. They read Hang a Thousand Trees With Ribbons. It’s a historical fiction about Phillis Wheatley, the first black woman published in the New World for her poetry. She’s great for my school because she’s 13 years old, she’s a black girl, a slave, and she’s living in Boston. What I like about this book is it introduces us to Africa, that people in Africa had families and they loved each other. It introduces us to human evil that is everywhere. And it teaches the girls that, here is this black girl who’s like you, who has the same wants, needs, desires, academic ambitions that they do, but that her life is being defined in some ways by this incredibly evil institution. Even as her owners are kind to her, she still has to deal with oppression. That’s one of the things that I try very hard to do, is to make everybody that we study human.

What advice do you have for teachers who are uncomfortable teaching about slavery?

Laura: Because my students are so young and they’re Northerners, they often want to think [slavery was] a Southern problem. Or they’re really curious about “How could Northerners allow this to happen?”

And so one of the things I like talking about is the fact that most of them own clothes that were made in Bangladesh or an iPhone that was made in a sweatshop in China. Did they consider that? Did they worry about that? Are they writing their elected officials or boycotting Apple? And again, not to put white guilt onto them, per se, but to have them look at the complexity of these issues. And at the end of the day, they probably bought the T-shirt that was cheapest, without worrying about where it was made. So that’s one of the ways I try to connect it to current social justice issues.

Jackie: There’s a lot at stake if your discomfort with teaching about slavery makes you not do it or do it in a way that’s really superficial. The disservice that you’re doing to students is greater than the mistakes you might make when you try teaching it and sometimes fail. We’re all going to make mistakes teaching, but be reflective about where is your discomfort coming from.

I would say get drenched in the content because, once you’re in it, it is so clear how so many of the problems that we face in the United States, not only with race, but also with how we treat women and how we deal with labor, stem from our founding period as a slave nation.

Kevin: We see a legacy that lasts, and is so prevalent in just everything that we are doing today. I see it less as pieces of history that are separated than [as] chapters in the same book. You can’t mention a time in this country where racism and the effects of slavery haven’t been full force. We come out of [slavery]; we get Jim Crow. We come out of Jim Crow; we get the prison-industrial complex. Some would argue that the civil rights movement is still going on today. This is just the next chapter in this book that we’re in. And so, in talking about slavery, the connections to today, for me, are so obvious.

When teachers ask me about this stuff and how to teach about it, I feel like the best way to really start is to really, just like Jackie said, dig in and learn everything there and then get ready. Get ready for the struggles, right? Even I’ve had struggles as a black teacher teaching about slavery. Sometimes I feel like I’m almost militant in class. Which I feel like I’ve scared away some students from the subject. And not to be an apologist, but there is a certain balance there that I need to check, especially when teaching to white students who may not open up to me because they feel like I’ll yell at them because of it.

Ryan: [T]he advice I would give to teachers is to make a clear distinction between heritage and history. And this is something I do at the very beginning of my year for all my classes. So that heritage is the celebration of, the unquestioning of, it’s exactly what it is that we don’t want to do. That history is very critical, it’s full of questions, it’s filled with discomfort.

[W]e just had a monument that was removed in Lexington; it was a big deal. We actually have a Confederate monument down the street here at Centre College. No one’s made a big deal about it yet, but being able to have [conversations] about, “Well, that’s not really history. That’s more heritage. Let’s talk about heritage. Where are all the … monuments to slaves who had to endure this? Martin Luther King Jr. marched on Frankfort, which is our capital, but there’s no monument to Martin Luther King Jr.” So it’s getting into this larger conversation about how it is that we’re going to view what we view. I think it’s very important for teachers to do this, specifically, being able to cleave between what heritage means and what it represents and what history’s about.

Jackie: You need to be comfortable talking about race, and it’s OK to say black and white and talk about skin color—and those things matter. And I think that if you’re going to be uncomfortable talking about that, you’re not going to be effective talking about slavery. So get comfortable with naming skin color, naming race, because it does matter.

van der Valk is the deputy director for Teaching Tolerance.

As a result of our investigation, we identified several guiding principles for teaching about slavery:

Teach that slavery is foundational.

Slavery defined the nature and limits of American liberty; it significantly influenced the creation and development of major political and social institutions; and it was a cornerstone of the American prosperity that fueled our industrial revolution.

Acknowledge that slavery existed in the North and the South.

Slavery was legal in every one of the colonies that declared independence in 1776. Fewer than half (44 percent) of the high school seniors we surveyed knew that.

Talk explicitly about racism and white supremacy.

White supremacy provided the oxygen slavery required to persist—yet none of the 15 sets of state standards we reviewed for this report mentioned racism or white supremacy in the context of the history of slavery.

Rely on responsive pedagogy that is well suited to the topic.

When we asked teachers to tell us about their favorite lessons when teaching about slavery, dozens described classroom simulations, which are inappropriate for teaching about the deeply traumatic events surrounding enslavement.

Center the black experience.

Our tendency is to focus on what motivated the white actors within the system of chattel slavery. But, whether discussing the political, economic or social implications, the experiences of enslaved people must remain at the center of the conversation to do this topic justice.

Connect to the present.

Teach about the influences of African culture that still surround us. Point to examples of structural racism that can be traced back to slavery and white supremacy. Students must understand the scope and lasting impact of enslavement to gain a complete understanding of this history.

Preview one of the Inquiry Design Models featured in Teaching Hard History: American Slavery.