In the following excerpt from the 2019 collection Democratic Discord in Schools: Cases and Commentaries in Educational Ethics, Clint Smith responds to a case study titled “Bending Toward—or Away From—Racial Justice?” The study follows an instructional support specialist tasked with implementing a new, culturally responsive curriculum. The specialist faces challenges from families demonstrating white fragility and educators unwilling or unprepared to teach the new lessons.

From “Holding Complicated Truths Together Enhances Rigor”

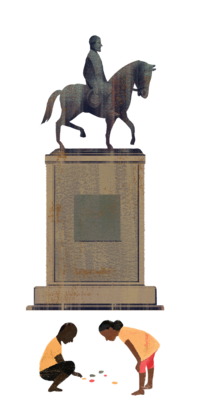

I was born and raised in a city that was filled with statues of White men on pedestals and Black children playing beneath them—where Black people played trumpets and trombones to drown out the Dixie song that still whistled in the wind. In New Orleans there are over one hundred schools, roads, and buildings named for Confederate soldiers and slave-owners. For decades, Black children have walked into buildings named after people who didn’t want them to exist.

What name is there for this violence? What do you call it when the road you walk on is named for those who imagined you under the noose? What do you call it when the roof over your head is named after people who would have wanted the bricks to crush you?

When I was a child I did not have a language for this, and it was not until much later in my life, through the work of teachers and texts, both formal and informal, that I have developed an ability to speak to the way that our country creates myths about who we are and who we have been. As a high school teacher, part of what I attempted to do in my classroom was to ensure that my students were equipped with the tools and the language to accurately name the world around them. I did not want them to experience the sense of paralysis I felt in knowing something was wrong, but not knowing how to name it as such. ...

Beyond providing the language for a young person to name the world around them, engaging with the histories we too often fail to name helps us better understand the contemporary landscape of inequality. One cannot begin to understand what happened to Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, without understanding the decades-long history of state-sanctioned housing segregation that created the conditions of the community in which he lived. One cannot begin to understand what happened at the White supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, without taking into account the ways in which the Sons and Daughters of the Confederacy warped the narrative of the Civil War into an ahistorical caricature of itself. One cannot begin to understand what happened to the nine victims of the Charleston church massacre without making sense of how, two hundred years ago, South Carolina was one of the single most important slave ports in the United States.

And yet, we find ourselves in a moment where our collective understanding of American history is wholly inadequate and purposefully inaccurate. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, only 8 percent of US high school seniors in 2018 were able to identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War.* ...

We do not have to choose between a rigorous lesson and a culturally responsive one. Our current political moment, and indeed our nation’s history, demands both.

The percentage of students who misunderstand the role of slavery in shaping the trajectory of this country is actually a microcosm for a much larger, more pernicious phenomenon in American life. Which is to say, we are so committed, often unconsciously, to the idea of American exceptionalism, that we often suppress anything that would render our history, and thus our country, unexceptional. In our classrooms across the country, our textbooks soften the contours of America’s most violent deeds and most malevolent people to present something more palatable, even if it is, as a result, dishonest. What is also true is that in the process of excavating unexplored truths, we simultaneously must wrestle with what it means to hold virtue and violence at once.

In my primary and secondary education I was taught that Abraham Lincoln was the great emancipator. I was taught that by sheer force of will and by the moral might of his pen he freed the slaves and set America on a trajectory of freedom and equality. I was not taught that in 1858, during the famous Lincoln-Douglas debate, Lincoln stated the following:

“I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races ... I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of Negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races from living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be a position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.**”

While Lincoln believed slavery was immoral, this passage illuminates how he also believed—at the same time—that Black people were neither equal to nor capable of living alongside their White counterparts. The fact that students are rarely invited to grapple with this dimension of Lincoln’s thought reflects the larger phenomenon in the pedagogy of American history in which those who are presented as opposing slavery, abolitionist or otherwise, are then assumed to have also believed in racial equality. But we know clearly that this was not the case. Lincoln seriously considered multiple plans for Blacks to recolonize in Central and South America both before and after emancipation.*** The truth, as Lincoln makes evident, is that it is fully possible for one to believe that Black people should not be held in forced bondage, and also fully possible that one still believes Black people to be inferior. It’s important to be clear about both beliefs, so that we are precise in our account of what the various actors in American history stood for and what they did not.

To be clear, there is much to admire about Lincoln. He possessed a laudable capacity to evolve in his political thinking, he led the nation through its most uncertain time and won a war that preserved the Union, and he did indeed act courageously in signing the Emancipation Proclamation. But that does not mean we should ignore the more unsavory aspects of his legacy. It is essential that we help students learn how to hold these complex truths as one in order to more fully understand the origins of our country, how those ideals wove their way into foundational policies we have always leaned on—and how these origins shape what our country is today.

Any culturally responsive history curriculum must hold these complicated dualities at once. The United States is a country of great opportunity, but we must wrestle with how certain opportunities are contingent on different facets of one’s identity. The United States has provided economic mobility for millions of people, but we must wrestle with the history of violence and exploitation that helped to generate its economic foundation. The United States has freed millions around the world from despots and genocide, and we must wrestle with this same country’s pervasive history of barbarous imperialism. These are all parts of what make this country what it is. Teachers attempting to bring American history into the classroom should not singularly focus on a false narrative of American exceptionalism, just as they should not singularly focus on its violence without accounting for its virtues.

Toward the end of the case, [one teacher] states, “If I have to choose between teaching a lesson that’s rigorous, and teaching one that’s culturally responsive, I’m going to choose rigorous...” [Her] perspective is one shared by many educators—those who believe a pedagogy meant to interrogate dominant modes of thinking about and seeing the world is one that is mutually exclusive from intellectual rigor. This could not be further from the truth. If anything, asking students to complicate their beliefs, and hold together a complex set of facts that don’t fit neatly into a specific ideological position, demands a level of cognitive dexterity that is often missing in our social studies curricula. We do not have to choose between a rigorous lesson and a culturally responsive one. Our current political moment, and indeed our nation’s history, demands both.

Citations

** “The Lincoln-Douglas Debates 4th Debate Part I: Mr. Lincoln’s Speech,” TeachingAmericanHistory.org, Ashbrook Center at Ashland University, 2018

*** See, for example, Phillip W. Magness and Sebastian N. Page, Colonization After Emancipation: Lincoln and the Movement for Black Resettlement (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2011)