Timothy McCarthy is an award-winning historian and lecturer in history and literature at Harvard University, where he also serves as Director of Culture Change & Social Justice Initiatives at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy. Recently, McCarthy sat down with Teaching Tolerance to talk about how Reconstruction has been historically contested and typically under-taught in schools, and why its lessons can provide signposts for anti-racist activists—and student leaders—today.

You’ve written about the fact that we as a country don’t have much of an appetite for commemorating Reconstruction. Why do you think that is?

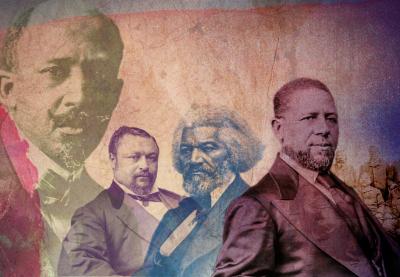

The Reconstruction era begins with emancipation and the abolition of slavery, and proceeds through the empowerment and enfranchisement of black men and a brief moment of American history where interracial government (at the state level) and black office holding (at the local, state and national levels) were a phenomenon for the first time. But it ends with the rise of white supremacy and of so-called “redeemer governments,” where white people took back power from black people who had been newly enfranchised and emancipated and empowered.

And that is not a happy ending. It’s an ending that points to the victory of white supremacy over interracial democracy. That is an ending of the era that I think people have a hard time wrapping their heads around, because it forces us to have a kind of racial reckoning about the realities of our country that are not always cause for celebration.

Reconstruction refers to the period that began in 1865, after the Civil War, and ended in 1877 when Rutherford B. Hayes pulled federal troops out of the South, removing protections for the rights of formerly enslaved people.

Why has the study of Reconstruction, historically, been a site of conflict?

Initially, the first formal historians of Reconstruction were—like many of the people who were part of the redeemer governments—white supremacists themselves. ... [W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1935 book] Black Reconstruction was an outlier and was written as a challenge to the historical profession, which had so far really only produced racist histories of Reconstruction.

But there’s also something else going on: It’s not just within the historical profession this [racist revisionism] is happening. There is a whole “lost cause” mythology that develops after the Civil War and certainly after the fall of Reconstruction. [It suggests] that somehow the antebellum period was a glorious heyday; that slaves were happy; that white people were heroes; that everybody was in their proper racial place. It’s a white supremacist ideology that looks to the antebellum period and to the Confederacy as the glory days. ...

Do you think historians today agree about Reconstruction? If anything, what facts are still in dispute?

I think it depends on which historians you’re talking about. Within the historical profession, there’s a pretty strong consensus at this point that Reconstruction was what Du Bois called “a splendid failure” and what my mentor, Eric Foner, has written was a great democratic drama in American history, where you have the first example of genuine interracial democracy in the United States. This is a period of enormous successes and revolutionary change in the South.

I think there’s a strong agreement that the history of black office holding—over 2,000 black men held office during Reconstruction at the local, state and even national level—that was a really important and unprecedented political reality that has to be acknowledged. ...We have much more debate culturally and politically [than we do among historians] about Reconstruction and about race and democracy and the South. We see this in the debates over Confederate monuments and whether or not they need to come down; the ways in which Donald Trump and members of his administration are actually trading in their own kind of “lost cause” mythologies. Donald Trump’s false equivalencies about Confederate generals and Confederate leaders and equating them with people like Lincoln and others is part of that. ... John Kelly made headlines trading in lost cause mythology, too, talking about “if only America could have compromised and then the Civil War wouldn't have had the kind of impact it had.”

It forces us to have a kind of racial reckoning about the realities of our country that are not always cause for celebration.

How did Reconstruction give rise to the KKK and other white supremacist groups?

A lot of the people who either owned slaves or wanted to own slaves in the antebellum period fought for the Confederacy and fought for the right to preserve a way of life that’s rooted in the foundation of slavery, the totalizing system of inequality, subordination, et cetera. Those are the people who become the KKK, who become the vigilante mobs, who become, ultimately, the lynching mobs. ...

I think what’s important to understand is that while these organizations are new and [during Reconstruction] they take on a ferocity and preside over their reign of racial terror in the South—which will lead to the lynching of thousands of black people in the period after Reconstruction in the 20th century, the rise of Jim Crow segregation in the South, and all these other things—that impulse to deny black people their humanity and to do violence against black bodies and black lives has been part of the nation’s history since before it was founded.

What lessons can we learn from the Reconstruction era as we attempt to resist white supremacy now?

In many cases, we’ve been here, or a version of here, before. … You can read that in two ways. You can read that as that’s very depressing; what we’re seeing now is just part of a long trend of white supremacy and racism and so forth in American history that continues through the whole history of the country. And that’s quite depressing.

But there’s another way to read it, which is how I prefer to read it, which is that this is a through-line in American history. Race and racism and white supremacy is one of the great narratives of the history of the United States. We ignore it or downplay it at our peril.

Just as there are all of these examples of white supremacy and anti-black racism that permeate through the history of the country, there are also examples like Reconstruction, like the abolitionist movement and others, the civil rights movement, which are all part of the long black freedom struggle. There are people who, at every turn in American history, resisted anti-black racism and white supremacy.

First and foremost [were] African Americans and other people who were their allies and who were in solidarity with them and who helped work on building and sustaining the movements for black freedom and equality. That’s what I like to focus on: that there are examples, there’s a radical tradition, there’s a tradition of resistance in American history that coincides with and interacts with that other history of racism and white supremacy.

...I also think it’s important to know your history, to know what we’re up against and to understand that there has been, for a very long time (at least 150 years in this country) a battle over the meaning and memory of the Civil War and its aftermath. Of course, Reconstruction plays a major role in the contested memory and meaning of that transformational moment in American history. It’s important for us to know that there are these battles so that we don’t just accept what’s given to us.

How do you think our national understanding of Reconstruction has influenced the debates surrounding Confederate monuments?

I think it’s striking that we have all of these memorials through the South, the Confederate “heroes” who were literally the military and political leaders of an insurrection. We have all of these ... and we don’t have any statues to slave rebels. There’s no Nat Turner memorial. ... We just opened the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which is a stunning experience. Why have we had a Holocaust Memorial in Washington, DC, and not a slavery memorial?

The Holocaust, as terrifying and terrible as it was, is not part of the history of the United States. It’s part of the history of Nazi, Germany. And yet we have an easier time reckoning with that terrible history of this other country, than we do reckoning with the terrible racist history of our own country. That says something about our unwillingness or inability or incapacity to reckon with the worst of our history, which is still part of our history.

We have to do that, but what’s happened in Charlottesville, what’s happening in the rise of white supremacy in the United States right now, is not something that is new. In fact, we saw this happen at the end of Reconstruction, which is another reason why we need to study Reconstruction—because it literally speaks directly to what’s happening right now in the history of the United States and the present. And it also is precisely why we don’t reckon with the history of Reconstruction—because it’s too painful to actually confront.

What recommendations or suggestions do you have for a history teachers who want to teach the Reconstruction era well and do it justice?

I say to everybody, “Go back to the original source; go to the root of things.” As much I admire historians—I am one, I think they’re important to the country, to any country—I think it’s also important for students to have the opportunity to go back to the primary documents and go back to the real source from the archives of what’s happening. Don’t just read an article that a historian wrote about Reconstruction. Go back and read the eight Reconstruction [state] constitutions. Go back and read the political speeches; go back and read Fredrick Douglass’ commemoration of Abraham Lincoln in 1876; go back and look at the visual images that came out of Reconstruction. Go back and look at the various cultural representations that showed up in novels and plays and newspapers and these kinds of things.

… That’s what historians do. I always try in my own classes, and I encourage other people in their own classes to do that—be their own historians.

Why is Reconstruction history particularly important to social justice and anti-bias educators?

If we only think about the teaching of history as a means to celebrate how awesome America is, then we’re not doing our job. Historians are not cheerleaders. Citizens should not be cheerleaders. That doesn’t mean we can’t appreciate things about our country and even love things about our country. There are things I certainly love about this country, but there are also things that are not worthy of love, but they are worthy of recognition. And they’re worthy of an honest engagement in what those things have done, that impact the history of the country and our ability to get along with each other. ... I think it’s essential. And if we have any hope of moving beyond these stubborn impasses and prejudices, this work will help us do that.

Editor’s note: Dr. McCarthy frequently collaborates with Facing History and Ourselves, the organization that provided the toolkit for this story.

Teach and learn about the Reconstruction era with resources—including videos, texts, lessons and a unit plan—from Facing History and Ourselves.